By Randall Smith

Closed-end funds, the has-beens of the mutual-fund world, are

getting a chance for a second life.

The flood of investment dollars into low-cost index funds has

challenged many of Wall Street's most expensive offerings, few more

so than closed-end funds. In the decade after the financial crisis,

assets under management doubled in stock and bond mutual funds but

remained stagnant in closed-end funds, where the total in July

stood at $254.7 billion. Annual average new-issue volume,

meanwhile, fell from $13.2 billion in the decade ended in 2013 to

$2 billion for the next five years, according to Dealogic.

But now some big-name fund managers, led by TIAA's Nuveen and

BlackRock Inc., the top two closed-end sponsors, are making moves

to revive the sector, in part by revamping their structure. These

moves include having the fund sponsors, not investors, pay the

sales commissions that brokerage firms charge for selling the

funds. New closed-end funds also come with term limits that give

investors the option of getting out at par after a certain number

of years.

Closed-end funds generally offer higher yields than open-end,

often increased by borrowing, which also adds to risk. Those yields

can be tempting in today's low-rate environment. But average

investors shouldn't take the plunge without understanding the

higher fees and risks. The average expense ratio for these funds,

for example, is currently more than double the average for actively

managed open-end funds, according to Morningstar. And the risks

were on display in this year's market plunge, when several energy

funds were forced by their use of borrowing to sell assets or

liquidate.

What closed-ends are

While ordinary open-end funds expand or shrink based on

investors' purchases and sales, closed-end funds maintain a more

stable asset level because they issue shares as public companies.

Their shares may trade at a premium, or more often a discount, to

the value of their holdings.

Closed-end funds were in vogue in the 1980s, offering access to

star managers like John Templeton, Martin Zweig and Mario Gabelli.

In the 1990s a run of "country funds" featured stocks from Taiwan

or South Korea that weren't then widely available.

Since then, bond funds have come to dominate the closed-end

sector. Falling interest rates have served as a tailwind for

performance. Annual returns of closed-end bond funds topped those

of active open bond funds in the decade ended June 30. (Closed-end

stock funds trailed active open-end stock funds during the period.)

Reasons for the higher expenses include borrowing costs, management

fees based on the extra debt-financed assets, and costs of

acquiring illiquid or hard-to-find assets.

A 2018 study by Diana Shao and Jay Ritter at the University of

Florida found that closed-end funds underperformed other funds by a

wide margin in their first year of existence. Yet Prof. Ritter

believes such funds can be useful as sources of high-yield income,

if bought at discounts in small doses to limit risk.

Mike Holland, a Wall Street executive who helped launch a

closed-end China fund in 1992 and remains a director of a

high-yield utility closed-end fund, says, "There are pockets of

this market where if you are very careful and very lucky you can do

quite well." But their allure has faded as lower-cost options have

proliferated, he adds.

Dave Lamb, head of closed-end funds at Nuveen, says their

ability to deliver higher distributions by using leverage or

borrowing appeals to wealthier investors "approaching or in

retirement."

For example, the Nuveen AMT-Free Quality Municipal Income Fund

(NEA) has common stock valued at $4.4 billion, and borrows to boost

total assets by $2.5 billion. It had fees and expenses of 0.93% in

its latest full year, compared with 0.53% for a similar Nuveen

open-end fund. Its distributions were 4.4%, compared with 3.6% for

the open-end fund. But a drop in bond prices would hit the

closed-end fund harder.

Discounts and activists

The funds started struggling around 2014, as performance

weakened and the shares began trading at wider discounts of 10% or

more to net-asset value. A plunge in energy funds hit closed-end

stock funds' performance. That caused sales to slump and drew

vulture-like "activist" investors -- sharpening the need for action

by fund sponsors.

In response, the fund managers have tried to boost the funds'

appeal and narrow the discounts by paying the brokerage commissions

themselves, and by putting time limits on the funds' lifespan.

Thanks in part to pressure from the Investment Company

Institute, a fund-industry trade group, the closed-end sector also

has gotten help from the Securities and Exchange Commission against

attacks by activist investors. The SEC in May approved closed-end

funds' use of a Maryland law limiting the voting rights of

activists, thus potentially reducing the activists' ability to gain

control of funds or apply pressure for change.

Since 2019, new issues have rebounded, led by two BlackRock

stock funds, one for health science and the other for tech

companies. The two funds currently have $5.2 billon in assets

between them. Both funds have 12-year terms, and their expenses of

1.3% are one-third higher than BlackRock's comparable open-end

funds, in part because they aim to put some assets into

private-company stakes -- a more complicated task than simply

investing in publicly traded companies.

The activists' strategy, meanwhile, is typically to purchase

funds at discounted prices and then push for changes that could

narrow the discount and thus increase the market price of their

shares.

With a real or threatened proxy fight for control, they can push

a fund to liquidate or go open-end, both of which erase the

discount. Or they can push for a buyback of a percentage of the

fund's shares at a price close to par. Such scenarios often leave

the fund sponsors with fewer assets under management -- and fewer

fees.

Since 2015, activist investors led by Saba Capital Management LP

have engaged with managers of about 10% of all closed-end funds,

according to a Saba tally. They pushed 31 funds with a combined

market value of $6 billion to liquidate or go open-end. And they

persuaded 28 more to shrink by a total of 37% in dollar value via

buybacks.

Each fund's buyback reduces its number of shares outstanding,

without changing the per-share asset value. In buybacks, funds

offer a price close to full net asset value for a percentage of

their shares. The investors get cash for those shares, but the

funds' total assets shrink by the same percentage.

In the past year alone, Saba won a vote for board control of the

$701 million Voya Prime Rate Trust (PPR), according to AST Fund

Solutions LLC, a data, analytics, proxy advisory and solicitation

firm; Saba pressured two BlackRock muni funds valued at a combined

$107 million to go open-end; and it won buybacks near par of $605

million at three Legg Mason funds.

Saba founder Boaz Weinstein says his battles with fund managers

effectively "liberate thousands of investors from funds that charge

excessive fees," which cause the funds' persistent discounts.

After the SEC said it would allow funds in Maryland to limit

voting by holders of 10% stakes in closed-end funds, three fund

groups said 24 of their funds would "opt in" to the Maryland

limits. And BlackRock is moving five funds with $567 million in

combined value to Maryland via a series of mergers.

The risks of closed-ends' reliance on leverage was highlighted

earlier this year during the drop in energy-asset prices. Two

Goldman Sachs energy funds, sold for a combined $2.3 billion in

2013 and 2014, were abruptly forced to unwind an estimated $250

million of borrowings in March, liquidating some of their largest

holdings at distress prices. The result: life-of-fund losses of

95%.

And two Nuveen energy funds worth a total $698 million at their

offering prices in 2011 and 2014 had to be liquidated in May to

avoid bankruptcy, at asset values 93% below their IPOs. Prior

distributions offset more than one-quarter of the losses at the

Goldman funds and about half of the Nuveen funds' losses.

Mr. Smith, a former financial reporter for The Wall Street

Journal, is a writer in New York. He can be reached at

reports@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 07, 2020 20:44 ET (00:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

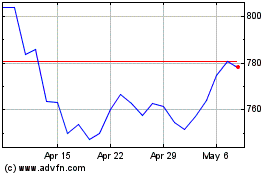

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

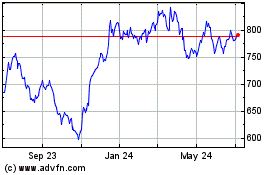

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024