By Peter Loftus

Diabetes patients are increasingly using electronic skin patches

and their phones, instead of pricking their fingers, to do the

complex job of managing a disease that affects more than 30 million

Americans.

The transformation in blood-sugar testing suggests how

harnessing technology and data may drive improvements for disease

management -- and profits for manufacturers.

Many patients now wear coin-sized skin patches on their arms or

abdomens that test for blood-sugar levels automatically, then send

the data to a patient's smartphone or even to a wearable insulin

pump that delivers the medicine.

Patients in the U.S. using the devices, known as

continuous-glucose monitors, numbered almost 840,000 as of March

31, more than double the 389,000 using them at the end of 2017,

according to Seagrove Partners LLC, a health-care research and

consulting firm.

Sales of the products are fueling growth at companies including

DexCom Inc., Abbott Laboratories and Medtronic PLC. Their sales of

the devices are expected to hit $3.2 billion this year, triple the

2016 total, according to JPMorgan Chase.

The market for the devices "is extremely large and growing

really fast," said Mike Hill, who heads the Medtronic unit selling

the sensors.

Tracking blood-sugar levels is vital for many diabetics, who

must regularly check if they are within healthy levels or need to

take insulin, sugar or some other medicine to avoid fainting or

worse. For years, many patients have had to prick their fingers

several times a day to draw blood and then insert the blood into a

meter for a reading.

Use of digital blood-sugar monitors, which first hit the market

in the mid-2000s, has soared in recent years partly because the

devices have become more accurate and more health plans are paying

for them.

"There's very few other diseases like this that put the bulk of

the data in the hands of the patient," said Aaron Kowalski, chief

executive of JDRF, a group that funds Type 1 diabetes research.

In Type 1 diabetes, the body doesn't produce insulin and

patients rely heavily on insulin therapy. In Type 2, the more

common type, the body doesn't use insulin properly.

With the connectivity linking monitors to smartphones and

insulin pumps come cybersecurity risks. The U.S. Food and Drug

Administration warned last month that certain models of Medtronic

insulin pumps could allow hackers to gain access, change settings

and cause patient harm.

Medtronic, which is recalling the pumps, said they were older

models and has recommended patients consider switching to newer

Medtronic models that have better cybersecurity protections.

The disposable sensors can be worn around the clock. They stick

to a patient's abdomen or arm and insert a tiny needle into the

skin to sense changes in blood sugar and transmit readings

wirelessly. Some patients have the glucose data sent to a wearable

insulin pump; some pumps can adjust the dose based on the glucose

reading.

Some monitors sound alarms and keep track of long-term data,

which patients can share with their physicians.

A DexCom-funded study published in JAMA in 2017 found that

patients using its monitor had greater decreases in average

blood-sugar levels than those using finger sticks and test

strips.

The data deluge, however, can overwhelm some patients,

especially new users. Some patients say they feel punished when the

monitor shows sugar levels are out of range and have asked for more

positive feedback when they stay in range, like a smiley face,

DexCom CEO Kevin Sayer said in an interview.

Raynham McArthur, a 14-year-old in Hamilton, Ontario, used to

wake up at midnight and 3 a.m. every night for her parents to take

blood samples. The multiple finger sticks left her fingers bruised

and sore.

Now, her sensor sends blood-sugar data to her parents' phones.

"I probably sleep through easily four nights a week," said her

mother, Joanna Wilson, a university science professor. She and her

husband, Andrew McArthur, monitor Raynham's sugar levels while she

is at school and text her to make sure she takes steps if the

numbers go out of range.

Raynham calls it "blood-sugar stalking." But the device made it

easier for her to go on a two-night school trip to Ottawa in June

without her parents. "It's a lot easier for me to go out and do

things with friends, " she said.

The cost, however, would be unaffordable for many patients who

lack insurance or whose insurer doesn't cover the devices, said

Mayer Davidson, a diabetes specialist at Charles R. Drew University

of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles.

Abbott's device, called FreeStyle Libre, costs around $1,308 a

year for the average patient; DexCom's system is about $3,000. With

insurance, the typical patient copay for Abbott's product is about

$31 a month, and $50 a month for DexCom's, said Erik Verhoef,

president of Seagrove Partners.

Competition for sales among device makers has been fierce.

Abbott priced its system at a significant discount to DexCom's to

grab an edge. Jared Watkin, senior vice president of Abbott's

diabetes-care unit, touts Libre's sensor, which lasts longer than

competitors'.

DexCom, which is working on a new version of its device with

Alphabet Inc.'s Verily unit, has been hiring data-analytics workers

to search for insights by pairing sugar data with exercise data

collected from other wearable devices, Mr. Sayer said.

Medtronic has used data collected from devices to develop

algorithms that predict when patients' blood-sugar levels will fall

too low, Mr. Hill said.

Write to Peter Loftus at peter.loftus@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 29, 2019 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

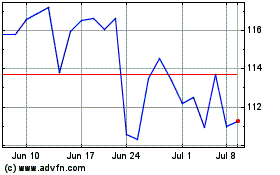

DexCom (NASDAQ:DXCM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

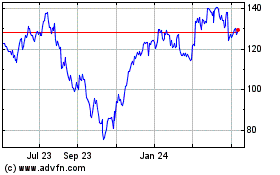

DexCom (NASDAQ:DXCM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024