By Liz Hoffman and Peter Rudegeair

Two dozen of Goldman Sachs Group Inc.'s most profitable traders

were kicked off their desk last year to make room for the swelling

ranks of the firm's Main Street lending arm.

Harit Talwar, the newcomers' Allbirds sneakers-wearing boss,

ribbed his counterpart, a Briton named Julian Salisbury who favors

crisp suits and ties knotted in a double Windsor. "Thanks for

making all the money we're spending," he said, according to a

person who heard the exchange.

With its core businesses of trading and deal-making on the wane,

Goldman has pushed into savings accounts and credit cards. Yet its

makeover is a money pit -- and is challenging its identity as a

titan of high finance.

Goldman's new consumer bank, which operates under the brand

Marcus, has lost $1.3 billion since launching in 2016. It spent

heavily to buy startups and cloud-storage space, hire hundreds of

techies, and build call centers in Utah and Texas. Loans have gone

bad at a higher rate than that of rivals.

Marcus launched without a collections team to chase down

delinquent borrowers, resulting in early loan losses, people

familiar with the matter said. A credit card developed with Apple

Inc. was a coup, but a costly one: Thousands of engineers across

Goldman were diverted to finish it in time for an August debut,

delaying other projects. Apple ads for the card carried the phrase:

"Designed by Apple, not a bank" -- a line that didn't appear in a

giant banner ad in Goldman's lobby this fall.

It's still early days, but Goldman has a lot riding on getting

this right. The firm brings in less revenue than it did in 2010.

Its stock trades below that of rivals with big consumer businesses,

which are now in vogue with investors for their predictability and

low-cost retail deposits.

Mr. Talwar's joke to Mr. Salisbury captures the tension between

Marcus and the dealmakers whose money it is burning through. Even

those who buy into Chief Executive David Solomon's vision of a more

well-rounded Goldman still wince as their bonus checks shrink, as

they likely will again this year. Dozens of long-tenured partners

are leaving.

The tension cuts both ways. Coders wooed from Silicon Valley had

their requests for MacBooks rejected by Goldman's compliance

department, employees said. Mr. Salisbury's traders, edged into a

corner of the 26th floor of the bank's headquarters, complained the

bathroom had become too crowded.

A poll commissioned by Goldman this spring asked Marcus

customers whether the brand was "downmarket," a heartburn-inducing

word at a firm known for advising billionaires and big

companies.

Meanwhile, the kind of loans Marcus offers are the first to go

bad in a recession and aren't backed by collateral, as home

mortgages are. Goldman pulled back on consumer lending this year

after losses were higher than expected, people familiar with the

matter said.

Executives say Marcus has helped lure tech talent to the firm

and has proven that Goldman can stand up new businesses. They also

point to the success of Marcus's savings accounts, which have

gathered $50 billion in deposits, a new type of low-cost funding

for the bank.

"We're developing muscles we didn't know we had," said Omer

Ismail, who runs Marcus in the U.S.

A hat bearing the letters MVP hangs on his office door, a gift

from the team. At the old Goldman, it would have meant "most

valuable player." At the new Goldman, it means "minimum viable

product," tech-speak for a new offering that is ready to be

launched -- if just barely.

Profit engines

For most of its 150-year history, Goldman dominated the high end

of finance. It virtually invented institutional stockbroking in the

1960s and the modern initial public offering in the 1980s. It

brokered $1.3 trillion worth of corporate mergers last year.

Those profit engines have sputtered since the financial crisis.

New regulations have reined in its securities traders, who earn

less than half the revenue they did a decade ago. Goldman once

invested billions of dollars of its own money into deals; that,

too, is off-limits now.

Goldman's stock is stuck at 2014 levels. Investors have flocked

instead to rivals such as JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of

America Corp., which churn out steady profits from lending and

money management.

Marcus, hatched at a 2014 gathering of executives in the

Hamptons, the exclusive New York enclave, was meant to get the firm

growing again. With a blank canvas and a generous budget,

executives believed they could pick off business from slower-moving

rivals.

Marcus debuted two years later to make personal loans of a few

thousand dollars. It also offered online savings accounts that

customers could open with as little as $1.

Naming the startup after the bank's 19th-century immigrant

founder gave it some distance from the Goldman brand, still tainted

by its role in the 2008 meltdown. Uncomfortable memories of the

crisis informed other early decisions.

Executives worried that aggressive debt-collection efforts would

dredge up a predatory image it had spent years trying to stamp out.

So Marcus launched without a team of specialists to contact

delinquent borrowers and try to recover what they owed, people

familiar with the matter said. When the first borrowers fell

behind, Goldman lost more money than it should have, those people

said.

The bank now has dedicated collections staff that is specially

trained, a spokesman said.

It still has higher loan losses than rivals. Goldman wrote off

$156 million in 2018 and another $155 million in the first six

months of 2019, according to public filings. In the year ending

June 30, its losses amounted to 5.5% of its loan book, higher than

peer Discover Financial Services and above the 4% estimate

previously given by Goldman executives.

Though the bank was wary of being heavy-handed in collecting

debt, in at least one case it overstepped.

Last August, an Oklahoma woman filed for bankruptcy with debts

that included a $19,894 Marcus loan. As is standard in personal

bankruptcies, the court barred Goldman from attempting to collect

the debt.

Goldman contacted her nine times over the next two weeks seeking

repayment, even after her lawyer sent another letter notifying the

bank that she had filed for bankruptcy, the woman alleged in court

filings.

Goldman settled the case.

'Not a bank'

Goldman doesn't have a brand that consumers know or physical

branches to pull them in off the street. So it is looking for other

ways to get the word out, acquiring or partnering with well-known

brands that can bring their own customers and cachet.

It is pitching corporate human-resource officers on

"Marcus@Work," which offers financial education to employees. It is

also in talks with AARP, the retiree organization, to provide

banking services to its 38 million members, people familiar with

the matter said.

Last year it acquired Clarity Money, a personal finance app with

more than 1 million users. It is one of several suitors eyeing

GreenSky Inc., an online lender that is exploring a sale, according

to people familiar with the matter.

AARP and Goldman declined to comment. GreenSky didn't respond to

a request for comment.

Finding customers through well-known partners spares Goldman the

hassle of building a network branches and sending out millions of

pieces of direct mail, as Marcus did in its early days.

But it casts Goldman as a vendor that, in most cases, needs

those partners more than they need it.

That imbalance was on display in its partnership with Apple to

launch a credit card, Goldman's first. The cost of beating out

other banks was accepting a number of demands from Apple, which is

famously design-obsessed and exacting in its dealings with

partners, according to people familiar with the matter.

Goldman agreed not to charge late fees or sell customer data,

trading away two key ways that credit-card issuers make money.

Apple wanted control over the monthly statements sent to

cardholders, pushing for jargon-free disclosures and its own

signature font. Goldman's lawyers warned that veering from standard

industry language could invite regulatory problems, but the bank

compromised. Apple got its font and Goldman trimmed the fine

print.

Apple and Goldman declined to comment.

Apple initially wanted to charge everyone the same interest

rate, regardless of their credit scores, people familiar with the

matter said. On this point, Goldman pushed back. The card currently

charges rates between 13% and 24%.

When Apple unveiled the credit card on stage in March in

Cupertino, Calif., it did so with a zinger: "Designed by Apple, not

a bank." Mr. Solomon and other Goldman executives watched from the

audience. The same line was repeated in ads that Apple ran

promoting the card.

In a final snub, Marcus executives weren't allowed into a

Tribeca loft that served as Apple's command center in the days

leading up to the card's launch in August.

Even beyond the roughly $300 million Goldman spent to build it,

the Apple card was a drain on the firm's resources. When early

testing of the software this spring revealed a security

vulnerability, Goldman reassigned thousands of engineers from

around the firm to patch it, people familiar with the matter

said.

That put other initiatives months behind schedule, these people

said. A Marcus budgeting app and a digital wealth-management tool

that had been planned for early next year are now expected in late

2020 at the earliest.

Executives say the costs are justified by the chance to reach

hundreds of millions of iPhone users, a young, affluent bunch who

might be converted into Marcus customers.

In particular, Goldman wants their deposit dollars, a cheap

source of funding for the bank. Every $10 billion raised in

deposits saves Goldman $100 million a year, Goldman's chief

financial officer, Stephen Scherr said in April.

Identity crisis

Three years in, Goldman hasn't settled on an identity for

Marcus. It has been cast both as a buzzy Silicon Valley startup,

where coders sip kombucha from a tap at a WeWork office in San

Francisco, and as a nostalgic throwback, its logo a simple M on the

type of wooden sign that might swing from a small-town general

store.

The Goldman poll this spring asked customers to imagine Marcus

as a party guest. Is he a spunky teenager or a chill boomer? Does

he drive a minivan or a hybrid? Is he standing alone by the snack

table or DJ'ing? Is he playful, hardworking, cultured or cool?

Users earned Amazon gift cards for their feedback.

Even Marcus's products don't fit easily together. It pitches

personal loans to cash-strapped consumers who need money to fund

home renovations or pay off other debt. Its high-yield savings

accounts are marketed to wealthier individuals with cash lying

around. Marcus is courting tech-savvy consumers but doesn't have a

smartphone app.

Meshing Goldman's buttoned-up culture with an influx of new

talent has also been a challenge, executives say. Marcus has hired

some 500 people from rival consumer banks and another 500 from tech

companies, according to a spokesman.

Marcus acquired four tech startups including Clarity Money, a

personal-finance app whose founder, Adam Dell, zipped around

Goldman's headquarters on a hoverboard until it was confiscated by

legal staff after someone crashed it, people familiar with the

matter said.

Marketing staffers, drawn from companies including PepsiCo and

American Express Co., churn out jingles that aired on sports radio

this fall. ("I feel like a smart money guy," chimes a middle-aged

man, "now that my savings rate is high.")

As Marcus heads toward its third birthday, turnover has spiked

-- some of it welcome by senior executives, who say they have

learned more about what it takes to run a consumer business. Marcus

has had three heads of product in three years. Its chief risk

officer went to Barclays PLC. Darin Cline, the operations chief who

walked the call-center floor in Utah in cowboy boots, left earlier

this year.

As Marcus becomes more central to Goldman's future, executives

have discussed phasing out its name entirely, people familiar with

the matter said. Goldman is already killing off other brands it has

acquired in its push onto Main Street, including wealth manager

United Capital and 401(k) startup Honest Dollar, whose logo's shade

of cornflower blue Goldman spent months perfecting.

Mr. Solomon, according to people familiar with the matter,

favors a single brand on the firm's consumer products: Goldman

Sachs.

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com and Peter Rudegeair

at Peter.Rudegeair@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 28, 2019 00:15 ET (04:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

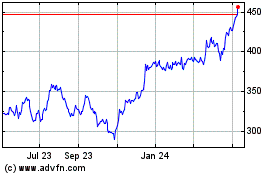

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

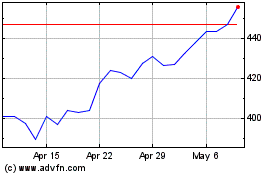

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024