By Alistair Barr And Mike Ramsey

Google Inc. designed its self-driving cars to follow the rules

of the road. Now it's teaching them to drive like people, by

cutting corners, edging into intersections and crossing

double-yellow lines.

Humans expect drivers to avoid collisions. But Google's robots

assume the worst and tap the brakes frequently as their digital

"eyes" spot potential dangers, sometimes prompting other drivers to

stop abruptly.

The cars are "a little more cautious than they need to be,"

Chris Urmson, who leads Google's effort to develop driverless cars,

told a conference in July. "We are trying to make them drive more

humanistically."

Google is moving closer to commercializing self-driving cars,

with the hiring earlier this month of auto-industry veteran John

Krafcik as chief executive of its car project. One big remaining

challenge is to make the cars, which have run more than a million

miles on public roads, move more seamlessly among human

drivers.

Since 2009, the cars have been involved in 16 minor accidents.

In 12 of those mishaps, the vehicles were rear-ended. That's a

higher accident rate than the national average, but Google says

national statistics exclude many minor accidents similar to those

its cars have experienced.

Google said it wasn't at fault in any of the crashes. But some

allies say the vehicles' habit of braking to avoid real, but

marginal, risks may play a role.

"Why is it getting rear-ended? It drives like a computer," said

Jen-Hsun Huang, chief executive of Nvidia Corp., which designs

powerful graphics processors that help Google's cars recognize

objects.

Mr. Huang said Google could remedy the problem with "deep

learning" techniques that help computers recognize images and

objects, and then improve over time.

During a recent test drive involving two Wall Street Journal

reporters, the Google Lexus RX450h autonomous vehicle jabbed or

tapped the brakes at seemingly odd times.

In one instance, the Lexus hit the brakes because it interpreted

that a car approaching fast from behind might cut it off as it

passed. The other car didn't do that, creating a sense that the

Google car slowed for no reason.

Another time, the car stopped at a busy T-intersection with

limited views of cross traffic. It waited for about 30 seconds,

began to make a left turn, but stopped in the middle of the

intersection as a woman on the other side of the street walked near

the edge of the sidewalk.

"I think that split-second we were yielding for a potential

person crossing the crosswalk," said Nathaniel Fairfield, a Google

team leader who was conducting the test drive. "Better behavior

there would be to not have stopped abruptly."

Mr. Fairfield logged the incident on a laptop and said Google

would study it to consider changes to the computer instructions

that guide the car. The event was also stored in a library of

driving scenarios that Google uses to test whether changing one

pattern might trigger unsafe behavior in other situations.

Still, Mr. Fairfield insisted that the cautious approach wasn't

causing other drivers to rear-end the autonomous vehicles.

"We clearly are a little jerkier than we would like," he said.

"But all of these cases have been when we are sitting still."

Some drivers around Google's headquarters in Mountain View,

Calif., say they find the cars annoying. They inch forward at T

intersections, pausing regularly to get their bearings. They're

extra careful when turning left because their software calculates a

minimum safe turning distance from oncoming traffic. Humans have a

more instinctive, and higher risk, assessment.

Google's cars used to make wide left turns. But those turns

confused other drivers and felt "weird" to passengers, Mr.

Fairfield said.

By studying human turning patterns, Google saw that people take

corners more directly, turning earlier, "cheating in the turns" as

Mr. Fairfield puts it. So Google baked that into its

algorithms.

Twelve minutes into the test drive, Google's car drifted toward

the center of a two-way street, driving over the double-yellow line

to get around a parked car--the result of another change. Google

once forbid its cars from crossing a double yellow. But that proved

impractical when parked cars blocked the road, and Google's car had

to stop indefinitely.

"It's just unnatural and bizarre," Mr. Fairfield said. "You want

to figure out when the right time is to relax things a little

bit."

At stop signs, Google adopted a "creep" function to show other

drivers its car intends to proceed. Otherwise, at four-way stops it

might continue to wait until the intersection was clear.

The cars still slow down or stop when they're unsure of what's

going on.

Google now is building human flexibility and interpretation into

more of these unusual cases. If a traffic light is out and other

cars are treating the intersection as a four-way stop, Google's

cars will sense that and do likewise.

Write to Alistair Barr at alistair.barr@wsj.com and Mike Ramsey

at michael.ramsey@wsj.com

Subscribe to WSJ: http://online.wsj.com?mod=djnwires

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 28, 2015 14:17 ET (18:17 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

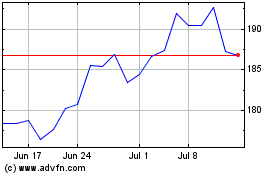

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

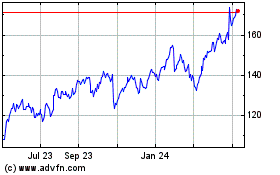

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024