By Alistair MacDonald and Ben Dummett

The vast majority of the world's gold miners have yet to join

the wave of mergers reshaping the top of their sector, even as

investors say more tie-ups are necessary amid poor returns and

depreciating gold reserves.

Since the bursting of the commodity bubble in 2011, bankers and

investors have predicted the thousands of small and midsize gold

miners that populate this sector would merge.

This week, the sector's largest companies, Barrick Gold Corp and

Newmont Mining Corp said they would form a Nevada joint venture

that, if a separate company, would be the third-biggest producer of

gold in the world. Last fall, Barrick also bought Randgold

Resources and in January Newmont bought Goldcorp Inc.

But the rest of the sector has yet to join in. The industry

feels burned by past mergers and acquisitions where purchasers

overpaid for assets. Many companies are unwilling to sell with

share prices so low and, according to investors, because entrenched

management doesn't want to put its well-paying jobs and lofty

positions at risk.

"Capital has become more difficult for companies to access and

important to that access is scale and liquidity, and some of those

companies don't have the size to attract that attention," said

Douglas B. Groh, a fund manager at Tocqueville Asset

Management.

Last year, there were 637 mining deals worth $59.6 billion, down

55% from the 2011 peak, according to data provider Dealogic. Over

the same period, there were 784 oil and gas deals worth $340

billion, the highest value in the last decade.

Some managers have struggled to sell. Africa-focused Roxgold

Inc. has been trying to sell itself for some time and is currently

involved in discussions with at least one party, according to

people familiar with the matter.

Kinross Gold Corp. has been trying to sell its 90%-owned Chirano

mine in Ghana for more than a year without reaching an agreement,

given what some potential buyers see as a high price, according to

a person familiar with the matter.

Roxgold and Kinross declined to comment.

Miners and bankers give a variety of reasons for why the gold

mining merger wave hasn't come. The poor performance of gold

miners' shares means that sellers want to hold out for better

valuations and buyers are reluctant to use shares they believe are

undervalued for acquisitions.

The S&P TSX Global Gold Index is down 51% since its 2011.

The S&P 500 has doubled in value in that time.

The industry as whole has a poor record in M&A. Miners

overspent during the decadelong bubble that ended in 2011. That put

off investors and made some executives wary of doing deals.

In 2016, PwC calculated that big miners had written off $200

billion of the value in acquisitions and projects over the previous

five years.

Executives may be reluctant for another reason, investors say.

They don't want to put themselves out of a well-paid job by merging

or selling their mines.

In Canada, for instance, chief executives and presidents of

mining companies they surveyed received a basic salary of C$200,000

and C$400,000 ($149,400 and $298,800) in 2017, according to

recruitment consultants Hays. That was the highest wage among the

various sectors in Canada that Hays surveyed. Those high wages came

despite poor returns from the sector.

Between 2010 and 2016, Yamana Gold Inc. paid its CEO over $60

million, according to research by Paulson & Co, despite its

share price falling by almost 70% in the period.

"There are probably too many gold companies around with poor

managers, so get these gold miners in stronger management hands,"

said Joe Foster, who runs the VanEck International Investors Gold

Fund.

Investors' lack of interest is a factor pushing for

consolidation, with miners needing to bulk up to get attention. For

smaller miners, the ascendance of index funds has made it harder to

attract money, because they aren't in the markets that these

investment vehicles track.

In Canada alone, there were 1,184 miners listed on the Toronto

Stock Exchange and TSX Venture Exchange as of this January, with a

combined market cap of just C$271 billion.

Miners are also chasing a depreciating resource. The World Gold

Council estimated that the industry produced 3,244 tons of gold in

2018, with production peaking at 3,252 tons in 2016.

Even as these mines deplete, there have been very few new

discoveries to replace the lost production, the bank says.

Still, bankers and executives say companies are currently

talking and they say the much anticipated consolidation will

happen.

There were two smaller deals this week, including Newcrest, the

world's third-biggest listed gold company by market value, inking a

$806.5 million deal to buy a majority stake in a Canadian mine.

Tom Palmer, the chief operating officer of Newmont, said smaller

players are waiting to see what the bigger miners sell once they

have completed their mergers before they start their own

M&A.

"Fast forward two or three years, there will be countless more"

mergers, he said.

Write to Alistair MacDonald at alistair.macdonald@wsj.com and

Ben Dummett at ben.dummett@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 13, 2019 08:06 ET (12:06 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

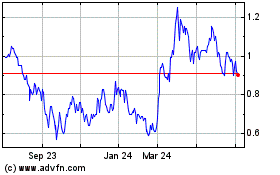

Augusta Gold (TSX:G)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

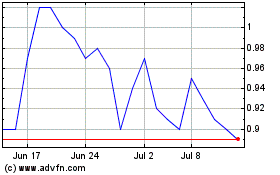

Augusta Gold (TSX:G)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024