By Ben Eisen

A long list of challenges confronted Wells Fargo & Co. Chief

Executive Charles Scharf when he was brought in to restore the

bank's tarnished reputation. In the year since, his problems have

only multiplied.

America's fourth-largest bank is in the grip of a recession that

threatens to deliver steep loan losses. Near-zero interest rates

are straining profit margins. And the bank is still in hot water

with regulators, which imposed a growth cap as a result of the

bank's four-year-old fake-account scandal and the plethora of

problems it exposed.

Then there are the self-inflicted wounds. Mr. Scharf has drawn

fire from employees and Washington lawmakers for filling top jobs

with a largely white, largely male cadre of former colleagues --

and for saying there were few Black candidates with the required

experience for those positions. The episode damaged morale within

the bank, especially among Black staffers, current and former

employees said.

Mr. Scharf had little room for error when he came to Wells Fargo

last October from Bank of New York Mellon Corp., pledging to clean

up a mess that started in its branches and spread to nearly every

one of its businesses. Two CEOs had already resigned after failing

to convince Washington regulators and lawmakers that the bank was

on the mend.

As he heads into his second year on the job, Mr. Scharf finds

himself in a position familiar to his predecessors: playing

defense.

Mr. Scharf is "focused on resolving important regulatory issues

created by past misconduct, putting the right leadership team in

place, and building an organizational foundation for Wells Fargo's

future success," a spokeswoman said in a statement. "He and his

team did this while also dealing with the negative impacts of the

COVID-19 pandemic and providing support for our customers and

communities."

When he became CEO, Mr. Scharf, a one-time protégé of JPMorgan

Chase & Co. CEO James Dimon, acknowledged the mistakes of the

past and swiftly attempted to remake the bank's insular culture.

"We need to be more direct with each other," he said at his first

employee town hall last fall.

He encouraged decisiveness. He mandated more rigorous

performance reviews. In some corners of the bank, people call him

"Chainsaw Charlie, " according to people inside the bank.

Mr. Scharf's defenders said he is laying the groundwork for the

company's rebound. Much of the progress, they said, is happening

behind the scenes -- in the vast web of systems and technology that

is meant to catch problems like the 2016 sales scandal.

He had some early wins. In February, the bank reached a $3

billion settlement to end civil and criminal investigations tied to

the sales scandal that had dogged the bank for years. He testified

before the House Financial Services Committee the following month

and -- unlike his predecessors -- emerged largely unscathed. He

raised minimum hourly pay in most of the bank's U.S. markets.

But 2020 has tested Mr. Scharf in unexpected ways.

The coronavirus recession threw Wells Fargo for a loop. The

bank, whose revenue has been falling for a few years, reported its

first loss since 2008 in the second quarter and slashed its

dividend. The bank, like its peers, has set aside billions of

dollars to cover bad loans. Its stock has lost more than half of

its value since the beginning of 2020. Analysts polled by FactSet

expect the bank to post a modest profit when it reports

third-quarter results next week, but still lower than a year

earlier.

Mr. Scharf has imposed steep cost cuts to help the bank weather

the downturn. Layoffs, expected to ultimately number in the tens of

thousands, have set employees on edge. Job cuts often happen on

Tuesdays, according to people familiar with the matter, and a new

policy instituted during Mr. Scharf's tenure requires laid-off

employees to leave immediately, instead of in 30 days.

Regulatory constraints, meanwhile, have complicated Mr. Scharf's

ability to steer the bank through the crisis.

When corporate customers rushed to draw down on their credit

lines in the pandemic's early days, Wells Fargo bumped up against

an asset cap imposed by the Federal Reserve as punishment for the

fake-account scandal.

The bank lobbied the Fed to lift the cap, arguing it was

constraining its ability to lend. The regulator granted the bank a

narrow and temporary reprieve so it could make loans under the

government's small-business rescue program, but it has declined to

lift the cap altogether.

Most recently, Mr. Scharf was criticized for comments he made

about the lack of Black talent at the most senior levels of

finance.

Mr. Scharf has brought in new leadership consisting largely of

white men he previously worked with in other finance jobs,

including at JPMorgan. The bank, meanwhile, has lost some of its

highest-ranking Black female employees, the Charlotte Observer

recently reported.

As of last year, Wells Fargo's executives and senior managers

were 87% white and less than 3% Black, according to company data.

In recent months, Mr. Scharf has hired three senior Black

executives, two of whom serve on the bank's powerful operating

committee.

In a June memo committing to diversify the company and its

senior ranks, he asked that employees withhold judgment until after

he had two years on the job to make progress.

"The unfortunate reality is that there is a very limited pool of

Black talent to recruit from with this specific experience," he

said, referring to the expertise needed to manage Wells Fargo's

regulatory issues.

Many workers were upset by his comments at the time,

particularly Black employees who were rising through the ranks.

When the comments resurfaced in a Reuters story in September, Mr.

Scharf was widely criticized. Staffers said they felt uncomfortable

having to defend the bank to people outside it.

The company initially tweeted this response from Mr. Scharf: "I

am sorry my comment has been misinterpreted." Later, in a letter to

employees, he wrote: "I apologize for making an insensitive comment

reflecting my own unconscious bias. There are many talented diverse

individuals working at Wells Fargo and throughout the financial

services industry and I never meant to imply otherwise."

On a Sept. 25 call arranged for a Black employee group, he took

a moment to acknowledge some of the many "well-written" letters he

had received from people around the bank in response to his

comments, according to people familiar with the call. That further

angered some employees, who likened it to when Black people are

praised for being articulate.

A Wells Fargo spokeswoman said: "While some may have heard

Charlie's comments differently, his intention was to convey that he

was moved by the thoughtful perspectives and insights that he had

received."

On the call, he also offered more context around his June

comments.

"If you look at the full paragraph and the full intent, there

was still plenty wrong with it, but I certainly didn't mean it the

way it's being portrayed more broadly," he said, according to a

recording reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. "Having said that, I

do understand it, and I think it is important that we use it as an

opportunity, and I've used it as an opportunity, to react to all

the things we've heard."

Write to Ben Eisen at ben.eisen@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 08, 2020 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

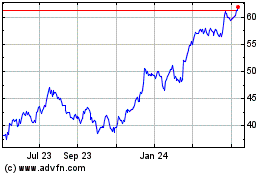

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

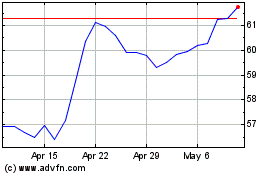

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024