By Michael Wursthorn

Morgan Stanley will scale back the recruitment loans it offers

to attract rival brokers to comply with new retirement regulations,

and competitors Merrill Lynch and Wells Fargo & Co. are

weighing similar moves, underscoring the far-reaching impact the

rules are having on the multitrillion-dollar financial-advice

industry.

Morgan Stanley executives, in a conference call with managers

Thursday, said the firm will immediately pull the incentive-laden

back-end portions of recruitment packages it offers brokers to

eliminate potential conflicts that are problematic under the Labor

Department's so-called fiduciary rule, according to a person with

knowledge of the situation.

Bank of America Corp.'s Merrill Lynch wealth-management unit and

the brokerage arm of Wells Fargo are weighing similar moves,

although no decisions have been reached, people familiar with the

matter said.

The Labor Department's fiduciary rule has been roiling the

wealth-management industry since the final draft was unveiled in

April, bringing with it significant changes to how retirement

savers pay for financial advice, how brokers have to put the

interests of those investors first and how they are

compensated.

Already, brokerages such as Merrill Lynch are contemplating a

future without retirement accounts that charge a commission,

putting the industry on a path further away from Wall Street's

traditional pay model in favor of accounts that charge a fee based

on a percentage of assets.

Now brokerages may be seeing the end of the costly but

often-used practice of recruiting experienced brokers from one

another to boost their assets under management. Morgan Stanley's

move and that of other brokerages -- if they follow suit -- would

slash the total value of such deals, which can range up to millions

of dollars for top-producing brokers, and could have broad

implications on how brokerages proceed with hiring practices around

experienced brokers.

It could also push more brokers to consider becoming independent

financial advisers who launch their own registered investment

advisory firms or join an existing one, experts say.

"It's a very difficult dilemma for the firms," said Rogge Dunn,

a labor attorney with Clouse Dunn LLP who works with brokers. "If

the packages are going down, that could mean the talented people at

the top go elsewhere, such as a RIA."

Brokerages frequently hire from one another. The four major U.S.

firms -- Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, UBS Group AG and Wells

Fargo Advisors -- entice brokers to jump from firm to firm by

offering hefty bonuses in the form of loans that are forgivable

over as long as nine years.

Deals typically pay three times the annual revenue a broker

generates off fees and commissions, structuring it so that up to

150% is paid out initially when the broker is hired, while the rest

has to be earned after hitting certain asset and revenue targets

over the life of the deal.

That back-end portion is problematic under the fiduciary rule,

which aims to eliminate incentives that might cause brokers to give

conflicted advice and ensure the interests of retirement savers are

put first.

"Such back-end awards can create acute conflicts of interest

that are inconsistent" with the rule, the Labor Department said in

new guidance to financial firms on Thursday. The guidance further

states firms may not use bonuses or other incentives that are

"intended or would reasonably be expected to cause advisers to make

recommendations that are not in the best interest of the retirement

investor."

That information has prompted brokerages to scramble to decide

how to proceed with those payouts.

The guidance could also have an impact on recruitment loans

handed out before the rule's release, Mr. Dunn said. Brokerages can

renegotiate those earlier deals or continue to honor them, but the

Labor Department wants heightened supervision of those brokers to

ensure conflicts are mitigated.

"The good news is the DOL recognized that many financial

advisers and firms entered into such arrangements before the

issuance of this [guidance]," Mr. Dunn said. "The bad news is that

some firms could take the position that they are required to rework

your contracts."

Industry executives say they expect recruitment deals to be

smaller going forward if the entire industry follows suit. Such a

move would help brokerages contain costs at a time when they are

spending heavily on compliance and supervisory systems to adhere to

the new regulations.

"Recruitment deals are going to change and not for the better"

for brokers, said Louis Diamond, vice president of Diamond

Consultants, a broker recruitment firm. He added firms may consider

alternatives to continue hiring brokers from one another, such as

higher salaries, which wouldn't be an issue under the rule.

Broker defections ramped up after 2004 when firms including

Morgan Stanley, Merrill and others signed the Protocol for Broker

Recruiting, an accord that helped limit the number of lawsuits and

arbitration claims filed over broker moves by outlining an orderly

system for brokers to change jobs. More than 1,200 securities firms

have signed the protocol since then.

Executives have bemoaned the costly practice in recent years,

with some referring to it as a "zero-sum game."

Earlier this year, UBS moved to slash its costs associated with

broker recruiting and said it would reduce by 40% the number of

brokers it poaches annually. It isn't clear if that decision was

based, in part, on the Labor Department's rule; a spokesman didn't

immediately respond to a request for comment.

Write to Michael Wursthorn at Michael.Wursthorn@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 28, 2016 16:51 ET (20:51 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

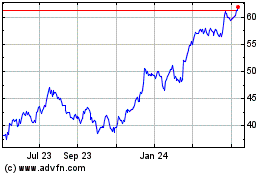

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

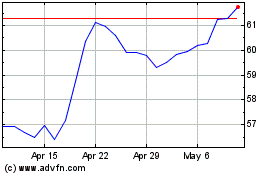

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024