By John W. Miller

FLORANGE, France--As ArcelorMittal, the world's biggest

steelmaker, looks to downsize in the U.S., it has an unlikely model

for industrial success: Europe.

This strip of rust-belt Northern France, known for its

cathedrals and white wines, has become the heart of ArcelorMittal's

most profitable business unit. The European Union, for all its

turmoil, is still the world's most prestigious automotive market,

where companies led by Germany's Audi AG and BMW AG make almost a

trillion dollars worth of cars annually.

To win a bigger share of the auto-making business, ArcelorMittal

invested heavily in developing new, lighter-weight forms of steel

and building galvanizing lines, even as it closed nine European

steel mills.

The company is also developing new approaches to make it less

reliant on the industry's traditional one-stop-shop integrated

mills. The new model, which it hopes in some ways replicate in the

U.S., is to design a network of plants knitted together by truck

and rail links.

Europe is "still leads the world in design and innovation,"

chief financial officer Aditya Mittal said in an interview. "It's a

place where aerospace, railway and automation technologies,

research into driverless cars, are all cutting edge."

By pushing forward in automotive, even in economically troubled

locales like Florange, ArcelorMittal has cemented its 50% share of

the European auto market. And success in the European rust belt,

even if not guaranteed to continue, offers an example for the

troubled steel industry at a time of crisis.

In the second quarter, with iron ore and steel prices falling,

ArcelorMittal, which makes 6% of the world's steel, said its sales

fell 18% to $16.9 billion from $20.7 billion a year ago. With the

U.S. market flooded with imports, prices in the country are down

over 20% since Jan. 1, and U.S. Steel Corp. has lost money in eight

of the past 10 quarters, and has laid off over 2,000 workers this

year. ArcelorMittal has also closed or idled mills and laid off

hundreds of workers in the U.S.

To be sure, Europe is hardly the ideal place to operate steel

plants. In addition to a sluggish economy and an influx of Chinese

imports, new rules on carbon emissions could cost the company over

a billion dollars a year by 2025. It is also no longer a dominant

steel market, consuming 150 million metric tons of steel a year. By

comparison, the Chinese steel market amounts to 750 million tons a

year. And in the U.S., which consumes 120 million tons of steel a

year, the aluminum industry has made inroads and is threatening to

take away more automotive market share.

The plant in Florange incarnates Europe's promise and perils. It

was built in 1964, in France's historical coal and iron-ore mining

region, and was part of the complex of steel mills that Indian

billionaire Lakshmi Mittal acquired when he bought Arcelor in 2006

for $33 billion.

That deal was the jewel in the crown for Mr. Mittal, who started

his career by building a steel plant in Indonesia, and set about

building a global steel empire. His model was to buy old

state-owned mills and make them more efficient, partly by cutting

costs and laying off workers when necessary.

His willingness to pull the trigger on downsizing set him up for

a clash with politicians and unions in post-financial crisis

Europe. In 2012, with European steel demand down 25% since 2007,

ArcelorMittal declared it would mothball Florange's two blast

furnaces. The plan became a defining issue of the 2012 French

presidential election, contributing to the economic malaise that

helped François Hollande defeat Nicolas Sarkozy.

"It didn't make sense to have these facilities far inland, where

there are no longer any mines, far from raw materials being shipped

in from the coast," says Aditya Mittal, who, as well as being CFO,

is the son of the company's founder.

French politicians, and the country's powerful labor unions were

livid. Then-industrial minister Arnaud Montebourg said the Mittals

were "no longer welcome in France."

ArcelorMittal agreed to invest $200 million in Florange in a new

finishing line that would make an aluminum-coated steel that could

compete with straight aluminum for the automotive market. The deal

defused calls for nationalization, although the company says the

two weren't linked.

The raw steel for Florange would come from a mill in coastal

Dunkirk, which has three blast furnaces and can produce 6.6 million

tons a year of steel. A nearby port unloads iron ore from

Australia, Brazil and Africa.

On a recent tour of Florange, workers demonstrated how slabs

from Dunkirk are rolled into kilometer-long (0.6-mile-long) coils.

Last year, Florange shipped out 1.2 million tons of finished steel.

Of that output, 46% goes to the automotive industry, 10% goes to

packaging--Europeans still drink beer and soda from cans made of

steel, not aluminum--and 44% goes into heavy industry.

Some union leaders say they still believe the company could have

kept the Florange blast furnaces. "But they have kept their word,

for the most part," says Patrick Auzanneau of the CFDT union.

Part of the changes at Florange involved changing the model from

stand-alone steel mill to a network of mills linked together by

rail and truck. It still had a functioning coke plant, a facility

that turns coal into a substance called coke used to make steel, in

Florange. The company decided to keep that open, and ship coke to

Dunkirk from Florange on the same trains transporting raw steel

slabs to Florange.

In the U.S., where ArcelorMittal snapped up a cluster of

bankrupt mills early in the past decade, the company is locked in a

battle with the United Steelworkers union, with a Sept. 1 deadline

to agree to a new three-year labor deal.

Lakshmi Mittal, in an interview last week, complained that his

firm was in an "unfair position" relative to other steelmakers and

aluminum companies. The company wants to cut wages for some

workers, and impose new health-care premiums. A USW official says

the company's proposals are "unfair" and "drastic."

Health-care costs are less of a problem for business in Europe,

because of the publicly subsidized, lower-cost health care systems,

compared with the U.S.'s expensive, private health-care system

poses an added burden. ArcelorMittal's U.S. operations have a

larger portion of older workers than in Europe, which would allow

it to reduce head count through retirement rather than layoffs. In

addition, because the U.S. still has considerable iron-ore mines in

the Midwest, it doesn't need to place a blast furnace mill on the

coast like it does in Europe.

"You can't replicate exactly what we did in Europe," says Aditya

Mittal. "But you can look at how to optimize assets, and Europe's a

good model for that."

Write to John W. Miller at john.miller@wsj.com

Subscribe to WSJ: http://online.wsj.com?mod=djnwires

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 24, 2015 19:33 ET (23:33 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

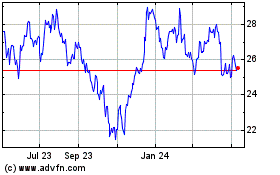

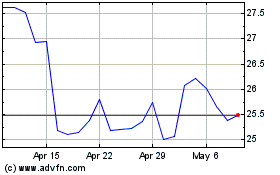

Arcelor Mittal (NYSE:MT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Arcelor Mittal (NYSE:MT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024