As chief executive of Massey Energy, Don Blankenship would hand

out cans of Dad's root beer to employees he was unhappy with and

explain that D-A-D-S stood for "Do As Don Says."

He explained the gesture as a good-natured reminder. "It's a

little bit easier to insist on people following the directions when

you do it in a fun way," Mr. Blankenship has said.

Few people would dispute that Mr. Blankenship, who once ran the

biggest coal company in Central Appalachia, was a micromanager and

a formidable boss. Whether his intense style also fueled a

conspiracy to violate federal workplace-safety laws ahead of the

worst U.S. coal-mining disaster in four decades will now be a

question for a jury to decide.

Prosecutions of CEOs are unusual, but not unheard of. Bernard

Ebbers was convicted in 2005 for securities fraud at MCI WorldCom

and sentenced to 25 years. Last month, Stewart Parnell, the former

owner of Peanut Corp. of America, was sentenced to 28 years, after

being convicted of presiding over a cover-up of salmonella

contamination in the company's products.

Mr. Blankenship, 65 years old, is the first CEO of a major U.S.

corporation to be charged criminally for conspiring to violate

workplace-safety rules following a deadly industrial accident, say

safety experts. Without tying Mr. Blankenship to the 2010 blast at

Massey's Upper Big Branch mine, in which 29 miners were killed, the

U.S. attorney in Charleston, W.Va., has said Mr. Blankenship

undermined safety at the company in the months before the

accident.

Mr. Blankenship has pleaded not guilty and vehemently denied the

charges in court filings leading up to a trial, which is set to

begin on Thursday.

"To elevate what is essentially an allegation of corporate

mismanagement into a federal crime is unprecedented," his lead

attorney, William Taylor, wrote in one filing earlier this

year.

Most of the charges against Mr. Blankenship, who faces a 30-year

maximum prison sentence, are tied to allegations of lying to the

Securities and Exchange Commission and investors about Massey's

safety record.

But the safety-related count against him is gaining the most

attention from legal experts, in part because of its rarity.

Between 1970 and 2008, company officials served a total of 42

months in all criminal prosecutions brought under the Occupational

Safety and Health Act, according to experts and federal records.

Since then, three officials have received prison terms for lying to

federal inspectors or falsifying safety documents, according to a

list of cases provided by the Labor Department. No CEO of a public

company has faced criminal charges for violating the nation's

current mine-safety laws since those were passed in 1977, say

experts.

"Successful prosecution of Blankenship will embolden prosecutors

to pursue similar cases," said David Uhlmann, a University of

Michigan law professor who served in the Justice Department under

former President George H.W. Bush.

Mr. Blankenship has long said that he expected retribution for

his antagonistic stance toward regulators investigating the UBB

disaster. "If they put me behind bars, it will be political," he

wrote on his personal website in 2013.

The prosecution's case is likely to focus largely on Mr.

Blankenship's direct involvement in decisions that affected safety

at Massey, which was the nation's fourth-largest coal operation in

2010 with $3 billion in revenue and 56 mines in West Virginia,

Kentucky and Virginia.

In a 41-page indictment, prosecutors cite a drumbeat of

handwritten memos by Mr. Blankenship allegedly urging managers to

keep the coal flowing at the highly profitable UBB mine. He weighed

in on decisions as small as whether to spend $750 to check

freeze-proofing systems at the UBB mine.

Many who worked with Mr. Blankenship, a former accountant,

attest to his uncanny grasp of numbers and operational details.

"He was a very thorough manager, and he was involved with all

major decisions," said E. Morgan Massey, the company's former

chairman. "You can call that micromanagement, but he spent 100% of

the time on the job, day and night."

Jeff Wilson recalled that when he was directing the construction

of the complex that would clean the coal mined at UBB, a $55

million project that took nearly a year, Mr. Blankenship would

often arrive by helicopter and stay until dark.

"Every morning, you would hear wha-wha-wha," Mr. Wilson said,

mimicking the blades of a helicopter. "Here he comes."

Mr. Wilson, who now runs his own energy consulting business in

Richmond, Va., prospered at Massey. But even so, he said Mr.

Blankenship would hand him a can of Dad's root beer when he wasn't

pleased. "It was a good prop, and it was effective," Mr. Wilson

said. "I was lucky I only got one can at a time."

Messrs. Massey and Wilson said they never saw Mr. Blankenship

order anyone to skirt safety laws.

Prosecutors, however, allege that Massey officials illegally

tipped off miners about imminent inspections so workers could fix

hazards and avoid fines and shutdowns. They also claim officials

falsified coal-dust samples. A buildup of coal dust was behind the

2010 explosion, state and federal investigators later

determined.

"You need to get low on UBB #1 and #2 and run some coal. We'll

worry about ventilation or other issues at an appropriate time,"

Mr. Blankenship wrote in one note cited in the indictment.

In another note, he reminded the group president who oversaw

UBB: "You have a kid to feed. Do your job."

Write to Kris Maher at kris.maher@wsj.com

Subscribe to WSJ: http://online.wsj.com?mod=djnwires

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 30, 2015 21:15 ET (01:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

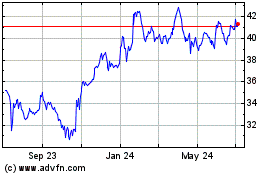

Verizon Communications (NYSE:VZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

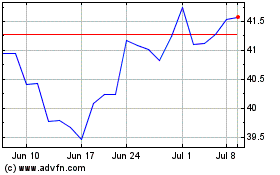

Verizon Communications (NYSE:VZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024