By Leslie Scism and Joann S. Lublin

Long before MetLife Inc. Chairman and Chief Executive Steven

Kandarian won his legal showdown with the U.S. government, he faced

doubters inside his own boardroom.

"What are the chances that we will win?" one skeptical director

asked before the giant insurer sued its regulators, according to a

person familiar with the situation.

"On the better side," he answered, according to another person

familiar with the conversation.

The decision to take on the federal government was a major

gamble for the 64-year-old Mr. Kandarian, a low-key executive known

for his caution and reserve.

MetLife was one of four nonbanks tagged by U.S. regulators as a

threat to the financial system, but it was the only company to go

to court to challenge that designation and the extra layer of

regulation it brings. The challenge risked customer and regulator

opprobrium.

Last week, the bet paid off: A federal judge agreed the December

2014 decision by U.S. regulators was flawed, freeing MetLife from

potentially higher capital requirements and other restrictions. In

her opinion, unsealed Thursday, the judge took regulators to task

for what she called an "unreasonable" decision to ignore the cost

of stricter supervision of the firm. The administration is expected

to appeal the ruling in the coming weeks.

"He has been vindicated," said Morgan Stanley President Colm

Kelleher, a friend of Mr. Kandarian's who also has a business

relationship with MetLife. "Many people thought it was a losing

battle."

Mr. Kandarian declined to be interviewed for this article.

The MetLife CEO seems an unlikely foe for Uncle Sam. A former

government official who ran the U.S. agency that insures private

pensions, he is quieter than his extroverted predecessors at

MetLife who were known for breaking into song at company events and

speaking to employees at town hall-style settings. He joined in

2005 as the insurer's chief investment officer.

Not long after becoming CEO in 2011, Mr. Kandarian began

preparing for a legal challenge, according to people familiar with

the events. He ultimately won over internal skeptics by promising

to avoid the bombastic language of all-out war.

MetLife's adversary was the Financial Stability Oversight

Council, a group of top financial regulators with the authority to

identify "systemically important financial institutions," or SIFIs,

that could threaten the U.S. economy should they fail in another

crisis.

General Electric Co. is dismantling its giant finance business,

GE Capital, after it was designated a SIFI, in part because the

regulations hurt its returns. American International Group Inc.,

too, has come under pressure from investors to break up to escape

the extra regulatory burden. MetLife itself has outlined plans to

shed a chunk of its U.S. life-insurance business for what it said

were strategic as well as regulatory reasons.

Mr. Kandarian's major concern was that the Federal Reserve would

require unusually thick capital cushions, forcing MetLife to raise

prices or quit lines of business. He said publicly that such

onerous oversight would put the company at a competitive

disadvantage when compared with rivals.

His view was that MetLife was swept up in "the overreaction and

overzealousness of regulators to prove they were doing something"

to prevent future financial crises, said one person familiar with

the situation.

The first step toward an eventual lawsuit came in November 2012,

when Mr. Kandarian reached out to a lawyer who is highly respected

for challenging federal agencies: Eugene Scalia, son of late

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and a partner at Gibson, Dunn

& Crutcher LLP.

It was still months before MetLife officially would come under

consideration as a SIFI, but Mr. Kandarian wanted help if MetLife

decided to turn to the courts.

"I was impressed that he was seeing around the corner...in a

legally sophisticated way," Mr. Scalia said.

Mr. Kandarian at this point was already frustrated with federal

regulators. In early 2012, an Internet bank owned by MetLife had

flunked a Federal Reserve "stress test" designed to gauge its

ability to absorb losses in another financial downturn. That test

result quashed MetLife's plans to buy back shares and raise its

dividend.

MetLife was the only life insurer tested, and Mr. Kandarian

complained publicly that the Fed's "bank centric" test didn't

reflect important distinctions between life insurers and banks,

which the Fed had historically regulated. Mr. Kandarian also

suggested that the Fed's math was wrong, a comment criticized by

some investors and analysts.

The experience "left a bad taste in [MetLife's] mouth," said

Ryan Krueger, a stock analyst with Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

Mr. Kandarian learned a public-relations lesson from the

stress-test failure and took his views about regulators behind

closed doors. He began discussing the prospect of tighter U.S.

scrutiny during nearly every private board meeting, people familiar

with the situation said.

When MetLife directors asked whether a lawsuit would harm the

company's reputation, alienate customers or antagonize regulators,

Mr. Kandarian promised a measured approach. During one board

discussion in October 2014, he said MetLife "was not declaring war

against the government," said one person familiar with the

conversation.

"Steve kept saying repeatedly, 'If we believe that the decision

is wrong as a matter of law, then it was important that we as a

company take advantage of our rights to due process and correct

what we believe is an irrational decision, as long as we did it in

a respectful way,' " said William Kennard, a MetLife independent

director and former Federal Communications Commission chairman.

When directors convened again that December, a month before

filing the lawsuit, Mr. Kandarian's deputies "wanted to be sure we

would be comfortable," a person familiar with the matter said.

Their plan to publicize MetLife's legal challenge was "very

analytical, void of hyperbole or malice" and designed "not to come

back to haunt the reputation of the business."

Mr. Kandarian made it clear at that meeting he thought the

company had a solid case. "We are even more convinced that we

should proceed," he said at the December 2014 meeting, according to

another person familiar with the situation.

When a federal judge handed Mr. Kandarian the legal victory he

predicted, he was on the phone with Mr. Kennard. "Wow, the decision

just came out, and it looks like we just won,'" he said, according

to Mr. Kennard.

Mr. Kandarian then emailed all board members about an hour later

with a muted celebration: "We were successful."

--Emily Glazer contributed to this article.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 07, 2016 15:02 ET (19:02 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

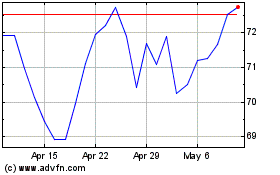

MetLife (NYSE:MET)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

MetLife (NYSE:MET)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024