CARACAS—Millions of pounds of provisions, stuffed into

three-dozen 747 cargo planes, arrived here from countries around

the world in recent months to service Venezuela's crippled

economy.

But instead of food and medicine, the planes carried another

resource that often runs scarce here: bills of Venezuela's

currency, the bolivar.

The shipments were part of the import of at least five billion

bank notes that President Nicolá s Maduro's administration

authorized over the latter half of 2015 as the government boosts

the supply of the country's increasingly worthless currency,

according to seven people familiar with the deals.

And the Venezuelan government isn't finished. In December, the

central bank began secret negotiations to order 10 billion more

bills, five of these people said, which would effectively double

the amount of cash in circulation. That order alone is well above

the eight billion notes the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European

Central Bank each print annually—dollars and euros that unlike

bolivars are used world-wide.

Four spokesmen from Venezuela's central bank didn't respond to

calls and emails seeking comment.

Economists say the purchases could exacerbate Venezuela's

economic meltdown: injecting large numbers of freshly printed notes

is likely to stoke inflation, which the International Monetary Fund

estimates will this year hit 720%, the world's highest rate.

Central-bank data show Venezuela in 2015 more than doubled

monetary liquidity, a measure used to gauge all money in the

economy, including bank deposits.

Printing more bolivars is weakening the currency further. This

week, the bolivar broke the psychologically important level of

1,000 per dollar for the first time on the country's thriving black

market.

The country has several official exchange rates, including 6.3

bolivars to the dollar. On Wednesday the country's trade and

investment minister, Jesú s Farí a, called for an overhaul of

currency controls. "It's evident that the current currency regime

has exhausted itself," he said in an interview.

Venezuela's 30 million people can't seem to get cash fast

enough, said Steve H. Hanke, an expert on troubled currencies at

Johns Hopkins University. "People want cash because they want to

get rid of it as fast as they can," he said.

While use of credit cards and bank transfers is up, Venezuelans

have to carry stacks of cash as many vendors try to avoid

transaction fees. Dinner at a nice restaurant can cost a brick-size

stack of bills. A cheese-stuffed corn cake—called an arepa—sells

for nearly 1,000 bolivars, requiring 10 bills of the

highest-denomination 100-bolivar bill, each worth less than 10 U.S.

cents.

Rigid state price controls have only made matters worse,

economists say, generating a thriving black market for just about

every good, from car tires to baby diapers, in which cash is the

preferred form of payment.

The bank-note buying spree is costing the cash-strapped leftist

government hundreds of millions of dollars, said all seven of the

people, who have been briefed on the deals Venezuela has entered

with bank-note producers.

The high cost of the printing binge is an especially heavy

burden as Venezuela reels from the oil-price collapse and 17 years

of free-spending socialist rule that have left state finances in

shambles.

Most countries around the world have outsourced bank-note

printing to private companies that can provide sophisticated

anticounterfeiting technologies like watermarks and security

strips. What drives Venezuela's orders is the sheer volume and

urgency of its currency needs.

The central bank's own printing presses in the industrial city

of Maracay don't have enough security paper and metal to print more

than a small portion of the country's bills, the people familiar

with the matter said. Their difficulties stem from the same dollar

shortages that have plagued Venezuela's centralized economy, as the

Maduro administration struggles to pay for imports of everything,

including cancer medication, toilet paper and insect repellent to

battle the mosquito-borne Zika virus.

That means Venezuela has to buy bolivars from abroad at any

cost. "It's easy money for a lot of these companies," one of the

people with details on the negotiations said.

The huge order for 10 billion notes can't be satisfied by any

single printera single firm, the people familiar with the deals

said. So it has generated interest from some of the world's largest

commercial printers, each vying for a piece of the pie at a time

when low profits in bank-note printing have pushed many of them to

cut back on capacity.

According to the people familiar with the deals, the companies

include the U.K.'s De La Rue, the Canadian Bank Note Co., France's

Oberthur Fiduciaire and a subsidiary of Munich-based Giesecke &

Devrient, which printed currency in 1920s Weimar Germany, when

citizens hauled wheelbarrows of cash to buy bread. More recently,

the German technology company was the source of security paper for

Zimbabwe when it was stricken in 2008 with a hyperinflation episode

in which prices doubled daily.

All of the printing firms declined to comment except the

Canadian company, which didn't respond to requests to comment.

Currency experts say the logistical challenges of importing and

storing massive quantities of bank notes underscore an undeniable

truth: Venezuela is spending a lot more than it needs because the

government hasn't printed a higher-denomination bank note—revealing

a misplaced fear, analysts say, that doing so would implicitly

acknowledge high inflation the government publicly denies.

"Big bills do not cause inflation. Big bills are the result of

inflation," said Owen W. Linzmayer, a San Francisco-based bank-note

expert and author who catalogs world currencies. "Larger bills can

actually save money for the central bank because instead of having

to replace 10 deteriorated notes, you only need five or one," he

said.

The Venezuelan central bank's latest orders have been

exclusively only for 100- and 50-bolivar notes, according to the

seven people familiar with the deals, because 20s, 10s, 5s and 2s

are worth less than the production cost.

Mr. Maduro and his allies say galloping consumer prices reflect

a capitalist conspiracy to destabilize the government.

The president in late December changed a law to give himself

full control over the central bank, stripping congressional

oversight just as his political opponents took control of the

National Assembly for the first time in 17 years.

"To stop excessive printing we have to undo that law and restore

autonomy to the central bank," said Elí as Matta, an opposition

lawmaker who focuses on state finances.

Central-bank data shows Venezuela more than doubled the supply

of 100-, 50- and 2-bolivar notes in 2015 as it doubled monetary

liquidity, a measure used to gauge all money in the economy,

including bank deposits. Supply has grown even as Venezuela has

fewer U.S. dollars to support new bolivars, a result of falling oil

prices.

The flood of money has led some sectors of the economy, such as

real estate and car sales, to effectively price their goods in U.S.

dollars, though they do so on the sly because dealing in foreign

currency is illegal. On the crime-ridden streets of Caracas, people

in the security industry say, professional kidnap-and-ransom teams

often demand U.S. currency instead of bolivars.

A color photocopy of a 100-bolivar bill costs more than the

note. In an image that went viral on social media, a diner is shown

using a 2-bolivar note to hold a greasy fried turnover because it

is cheaper than a napkin.

Some ATMs limit withdrawals to around 6,000 bolivars a day—less

than $6 on the unofficial market. Even so, the machines often run

out of cash. And in a sign of how quickly freshly printed bolivars

are rushed into the economy, the serial numbers on crisp bills

dispensed by ATMs are often in sequential order.

What clear is that there is little respect for the beleaguered

bolivar, regardless of what form it takes.

On a recent day, a 46-year-old slum-dweller named Mario walked

the streets of a wealthy district of Caracas with a megaphone,

calling on residents to sell him their coins, which he gathered

into a rolling water cooler. The idea: to melt it down later.

"You can make an amazing ring," said Mario, who wouldn't give

his last name but said he preferred to go by his nickname, Moneda,

or "Coins."

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 03, 2016 20:25 ET (01:25 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

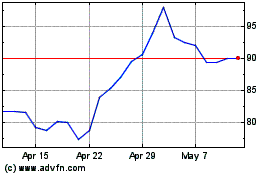

De La Rue (LSE:DLAR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

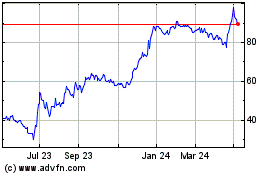

De La Rue (LSE:DLAR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024