By Benjamin Parkin and Paul Kiernan

BARÃO DE COCAIS, Brazil -- When Brazilian mining behemoth Vale

SA closed an iron-ore mine here earlier this year, it turned this

working-class town into a case study for a region whose traditional

industry is starting to slip away.

For centuries mining has been the lifeblood of communities

across Brazil's southeastern state of Minas Gerais, home to

colonial towns with baroque churches and ornate mansions built with

mineral wealth. Even today, Minas Gerais remains one of Brazil's

more prosperous states, thanks in large part to the jobs and

royalties generated by companies like Vale.

But a hollowing-out has begun, and concerns are growing that

this region could one day resemble the U.S. Rust Belt or

Appalachian coal country.

A thousand miles north, meanwhile, in the Carajás mountains of

the Amazon rain forest, Vale is putting the finishing touches on a

$14-billion mining complex known as S11D. Set to ramp up in the

coming months, it will crank out as much as 90 million tons a year

of the highest-quality, lowest-cost iron ore in the world. By 2018,

half of Vale's production is expected to come from Carajás, up from

39% extracted last year from its existing mines in the region.

That shift is beginning to be felt in towns like Barão de

Cocais, where the closure of Vale's Gongo Soco iron-ore mine in

April caused royalty payments to virtually dry up. Unemployment is

rising, shuttered houses and businesses line the streets and

municipal revenue is projected to fall by around one-fourth next

year.

"Mining finishes eventually," said mayor-elect Décio dos Santos,

adding that the town is ill-prepared for life without Vale. "We

need to think about more sustainable forms of development."

Decades of intensive mining have left Minas Gerais with depleted

deposits that are increasingly costly and less feasible to exploit,

with iron-ore prices crashing from nearly $200 a ton in 2011 to

below $40 earlier this year. Prices have since recovered somewhat

to around $80 currently.

Refining this lower-grade ore also produces large volumes of

waste that can be dangerous to store. After a dam failure at Vale's

Samarco joint venture in nearby Mariana last year killed 19 people,

company executives and local politicians say regulators have balked

at granting the licenses Vale would need to mine fresh deposits in

the region.

"The future here is not certain," said Karina Rapucci,

co-manager of Vale's nearby Brucutu iron-ore mine, the largest in

Minas Gerais.

As a result, Vale has increasingly focused its investments on

vast, untapped reserves in Carajás, where the ore is so rich it

generates little waste and is cheap enough to be profitable in

virtually any price scenario. Vale sees S11D bringing lower upkeep

costs and higher margins, ferrous minerals director Peter Poppinga

said in November. The new mine should enable the company to easily

offset depletion in its older pits, he added.

That bodes ill for Minas Gerais, where mining is still the

mainstay of many communities that have done little to diversify

their economies. Citing dwindling mining activity, Governor

Fernando Pimentel recently declared "financial calamity" as the

state struggles to maintain public services and pay salaries.

In Barão de Cocais, a town of around 30,000, royalty-fueled

building sprees spawned new government offices and public-sector

jobs. But without Gongo Soco to prop up the budget, Mr. dos Santos,

the incoming mayor, plans to lay people off and cut municipal

agencies next year, while potholed streets go unrepaired.

Unemployed miners like Júlio César dos Reis fear for the future.

Suffering from rare Graves' Eye Disease, he now no longer has the

health insurance to get the surgeries he needs.

"How am I going to find work...without treatment?" Mr. dos Reis

said.

A 40-minute drive east of Barão de Cocais, the town of São

Gonçalo do Rio Abaixo finds itself in a similarly vulnerable

spot.

Once a rural outpost where residents scraped by harvesting

bananas and sugar cane, the town was transformed almost overnight

in 2006 when Vale opened its Brucutu mine. Per capita gross

domestic product soared to more than $100,000 in 2014, on par with

San José in California's Silicon Valley. The unprecedented flood of

wealth spawned a new fleet of cars for city hall, a handsome

stadium and a gourmet burger joint.

But despite having fewer than 11,000 inhabitants, the local

government also increased its payroll almost 700% to 1,600 over the

past decade, highlighting a common practice in commodity-dependent

parts of Brazil.

Vale has already dug out the most of best ore from the Brucutu

sections within São Gonçalo's borders, meaning a likely decline in

the royalties to which the city has grown accustomed.

São Gonçalo's mining wealth came -- and is poised to fade -- so

quickly that it never touched some residents. Development

indicators like literacy and child-mortality rates lag behind

Brazilian averages. with 10% of the town's residents burning their

garbage at home. Scenes of crushing poverty are still to be found

along the dirt tracks leading off the town center's freshly

asphalted roads.

Conceição Moreira Duarte gets by on subsistence level with her

son and husband in the nearby woodland, surviving on government

benefits and her husband's sporadic salary as a day laborer.

"For us here, nothing has changed," she said.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 19, 2016 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

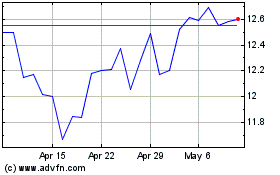

Vale (NYSE:VALE)

Historical Stock Chart

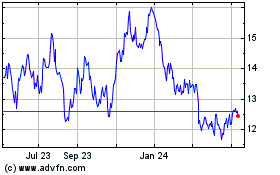

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Vale (NYSE:VALE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024