By Geoffrey A. Fowler

Hackers have us figured out.

They know we're busy. We're burning through email, texts and

posts about squirrels in lederhosen, too distracted to notice every

little click. So they've made a racket out of fooling us into

handing over valuable information. It happens faster than you can

say, "No, no, no, no -- what did I do?!"

Online cons are called phishing. If you're sure you already know

all about them, think again. Those grammatically challenged emails

from overseas "pharmacies" and Nigerian "princes" are yesterday's

news. They've been replaced by techniques so insidious, they could

leave any of us feeling like a sucker.

Just ask John Podesta, Hillary Clinton's campaign manager. Last

spring, he got snared by an email appearing to be from Google

asking him to reset his account. When he did, hackers gained access

to his email archive. The rest is history.

The past year's phishing catastrophes also included employee

identity theft at Snap Inc. and lost W-2 tax forms at dozens of

companies. About 97% of all cyberattacks start with phishing, says

Oren Falkowitz, chief executive of Area 1 Security. "It's the

biggest risk anyone faces."

Still don't think it could happen to you? Try to spot a warning

sign in this recent Gmail con: You get an email from someone you

know with a normal-looking attachment. Clicking on the attachment

opens a browser window with a normal-looking Google sign-in that

shows "accounts.google.com<http://accounts.google.com>" in

the address bar. Go ahead, type your login. Congratulations,

hackers now own your account.

What happened? That attachment was just a picture that launched

a login window on a phishing site. The only clue was a snippet of

code reading "data:text/html" in the address bar:

It's never been easier to be fooled online. That doesn't mean

we're defenseless. But the old rules of how to spot and stop these

attacks are no longer enough.

What They Want

"Most bad guys are working folks trying to make a buck," says

Mike Hanley, senior director of security at security firm Duo.

"Phishing is easy, and very profitable work."

Some phishermen try to trick you into clicking a link or

attachment that installs ransomware, locking your data until you

pay them . Others want to get you to type in your username and

password -- particularly for a corporate account -- so hackers can

slip in unnoticed. There's a vibrant black market for that info. A

login for a big corporation starts at $50, says Alex Holden of Hold

Security.

Sometimes phishers send out thousands of emails hoping to snag a

few victims. The Anti-Phishing Working Group, an industry

association, says 2016 broke records, with some 5,000 new phishing

sites popping up every day last spring. It's a game of Whac-A-Mole:

When one site gets shut down, another pops up.

Spear phishing is when phishers go after a specific person.

We've made their jobs easier by publishing so much about ourselves

on social networks. During tax season, phishers pose as a CEO

asking HR for employee records. The brunt of the damage is felt by

workers whose information gets exposed to identity theft.

How They Get You

Phishing usually happens via email, with alluring links or

attached files. Lately, it's also branching out to phones, text

messages, WhatsApp chats, Facebook pop-ups and search engines. I

once got phished by clicking an ad that downloaded malware to my

computer.

In the past, typos, odd graphics or weird email addresses gave

away phishing messages, but now, it's fairly easy for evildoers to

spoof an email address or copy a design perfectly.

Another old giveaway was the misfit web address at the top of

your browser, along with the lack of a secure lock icon. But now,

phishing campaigns sometimes run on secure websites, and confuse

things with really long addresses, says James Pleger, security

director at RiskIQ, which tracked 58 million phishing incidents in

2016.

The faster you're working, the more likely you are to click. Duo

sends faux phishing emails to employees to educate them. In test

runs at more than a thousand companies, 26% of recipients clicked

on emailed links, and 14% typed in their credentials.

Phishing is all about psychology -- social engineering. "The

techniques are always changing, but they're all preying on people's

confidence," says Daniel Ingevaldson, the CTO from Easy Solutions,

a security software company. They exploit your sense of urgency,

your desire to be responsible, or your relationships with the

important people in your life.

What You Can Do

It always pays to be vigilant. If an email doesn't feel right,

pick up the phone before you open an attachment or click a link. Or

even better, don't click at all: If you're told to sign in to, say,

Google or Verizon, type the address into a browser or open the

app.

But curbing phishing is a lot like preventing auto deaths --

training us to stay alert only goes so far. "Demanding perfection

from people doesn't make a lot of sense. Technology can fill that

gap," says Mr. Falkowitz, whose firm makes anti-phishing

software.

These days, known phishing websites are blocked automatically in

web browsers including Edge, Chrome, Safari and Firefox, though it

can take time for them to be discovered. A relatively new internet

mail standard called DMARC makes it harder for phishers to spoof

email addresses, though it isn't yet widely deployed. Developers

are using machine learning to cut off risky emails and websites

before they reach us. And big internet companies including Google,

Microsoft and Facebook automatically challenge logins that look

suspicious, and ask for additional verification.

Humans can help, of course -- primarily by keeping software

up-to-date: That scary Gmail trick I mentioned has been squashed in

the latest version of the Chrome browser. (Check yours by going to

Settings > About.) We can also make ourselves less valuable to

phishers by using different passwords everywhere -- which only Rain

Man could do without the aid of a password manager. (Dashlane and

LastPass are good options.) It's particularly important to protect

your email account, which can be used to reset other passwords if

someone takes it over.

Most of all, do this: Turn on an extra layer of security called

two-factor authentication (aka 2FA, two-step verification and login

approval). It's not foolproof, but it makes your password less

valuable if stolen. These systems, already used by many

corporations, usually ask for a code sent via text message or

generated by an app or security dongle.

Two-factor is available from Google, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft,

LinkedIn, Twitter and many other services. Though only a fraction

of people turn it on, it ought to be automatic for everyone with a

smartphone. Sure, logging in can be slow at times, but in an age of

aggressive phishing, I wouldn't be caught online without it.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 22, 2017 13:17 ET (18:17 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

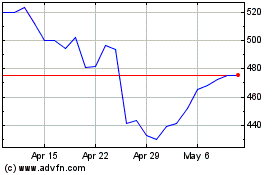

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

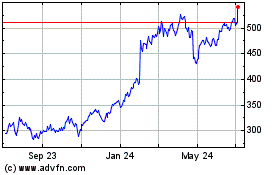

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024