By Jonathan D. Rockoff

French drug giant Sanofi SA is betting that a biotech

partnership named after a Star Trek premise will help it crack one

of the biggest mysteries in pharmaceutical research: molecules that

drive diseases, including some cancers, that have been considered

"undruggable" because of their shape.

Four-and-a-half years in, Sanofi now believes its partnership,

Warp Drive Bio, is close to getting its first new drug candidate.

But the path has been painful. The venture has gone through three

CEOs, two organizational structures, dizzying shifts in priorities

-- and so far, no marketable products.

Such challenges are playing out around the drug industry, which

had long relied on their own scientists to discover new products.

With a string of expensive failures, Big Pharma has come to realize

over the past decade that the science was getting too complex for

anyone to master alone.

Companies like Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson and others have

been re-engineering how they find new treatments, striking

partnerships with bright university researchers and deals with

promising biotechs. They have even agreed to work with one another

to better understand diseases.

"You can't do it alone. You have to say, 'Hey, we might have

been good in the past, but we need insights from others,' " says

Paul Stoffels, chief scientific officer at J&J.

About 70% of the industry's new sales today come from drugs

originated in small companies, up from 30% in 1990, according to

the Boston Consulting Group. And new-drug approvals are up from the

low levels of just a few years ago.

Yet pharmaceutical companies and their partners have struggled

to reconcile different personalities, distinct ways of working and

sometimes, competing goals.

"How do you stimulate innovation without killing it in the

process?" says Elias Zerhouni, Sanofi's research and development

chief.

The collaboration began in Paris in 2011, when Dr. Zerhouni was

just months into his new job, following stints at Johns Hopkins

University's medical school and 6 1/2 years running the National

Institutes of Health.

Sanofi's top sellers like the sleep aid Ambien and the

blood-thinner Plavix were losing patent protection. Yet since 2008,

the company had launched just three new products whose sales could

offset the losses.

Dr. Zerhouni, a physician and biomedical engineer who had

started five companies while in academia, figured that if Sanofi

was going to cure its innovation ills, it needed to collaborate

with world-class scientists outside of Big Pharma.

So one afternoon in May, he sat down with Harvard University

professor Gregory Verdine at the College de France in Paris. Dr.

Verdine had made groundbreaking discoveries at the crossroads of

biology and chemistry, and had formed seven companies that

developed drugs for hepatitis C and lymphoma.

Dr. Zerhouni grew excited as he listened to Dr. Verdine, hunched

over a computer in a small conference room, sketch out his idea for

an eighth company. He proposed a Holy Grail of drug research:

targeting proteins that are relatively flat and inside cells.

These proteins play pivotal roles in a lot of diseases,

including many cancers. But their flat surfaces protect them from

the current crop of biotech drugs, which typically work by locking

onto deep pockets in the proteins, outside cells, to stop them from

connecting to other important molecules.

They were considered "undruggable" because researchers had

failed to find a way to link a drug to one of these flat proteins

inside a cell.

Mother Nature had, though. A few bacteria, including one found

in the soil of Easter Island, did in certain situations make

molecules that could cross cell walls and connect with the flat

proteins inside. These molecules were the basis for drugs to help

patients recover from organ transplants.

Dr. Verdine was hoping to use the latest gene-mapping technology

to scour databases of bacteria for other similar bacteria. Some, he

figured, had to be able to hook to flat proteins and point the way

to new drugs.

You "don't need to tell me more," Dr. Zerhouni recalled

saying.

Dr. Verdine was ecstatic. After the economic downturn of 2008,

funding for life sciences startups was scarce. He had an interested

partner in Third Rock Ventures, a venture-capital firm based in

Boston that had been paying for a small team to begin the research.

But needed the support of a company such as Sanofi to fully engage

in the risky undertaking.

Such a collaboration between venture capital, Big Pharma and a

top scientist with a novel idea was highly unorthodox, and

negotiations took until Christmas.

Some things came easily. There was quick agreement on a name:

Warp Drive Bio, a homage to Star Trek that reflected the shared

goal of discovering new medicines rapidly -- at warp speed.

Other issues were tougher. Dr. Zerhouni, who admired Dr.

Verdine, nevertheless wanted the partnership to be led by someone

other than its scientific founder. "I didn't want to give money and

let some crazy professor run with it," Dr. Zerhouni recalls.

Dr. Verdine says there weren't any plans at that time for him to

run the company at its inception, and he was only on a one-year

sabbatical from Harvard.

Alexis Borisy, a partner at Third Rock Ventures who served as

Warp Drive's first chief executive, says: "We were making it up as

we went along. There was no model we could follow."

The final terms for Warp Drive Bio were unveiled Jan. 10, 2012.

Sanofi would give up to $87.5 million over five years to the

partnership. By then, Warp Drive Bio was to have delivered three to

five potential new drugs that Sanofi could test in humans. Sanofi

would have exclusive rights to the drugs and an option to buy the

rest of Warp Drive.

The company's first hires scavenged for bacteria to test,

drawing on collections kept by Sanofi, other drug companies and

government laboratories. They also swiped their own samples from

sidewalks, backyards, even during a wedding in California wine

country.

Within a few months, in March, the scientists had their first

hit. Researcher Keith Robison was poring over the genetic readouts

while in a rehab-center bed recovering from a skiing accident, when

he saw the telltale signs.

"This looks like the real deal," Dr. Robison emailed Dr. Verdine

later.

The bacteria had a cluster of genes, dubbed X1, that under the

right conditions should make molecules able to connect with flat

proteins. Dr. Verdine was right: Nature had made other microbes

with the special properties.

Over the months, Warp Drive sequenced tens of thousands more

bacteria. By summer 2013, the firm had found a dozen bacterial

strains making molecules with the special properties it was looking

for. But Warp Drive was far from discovering drug candidates.

Company researchers still had to uncover the molecules made by

these special bacteria and then the proteins that were targeted by

these molecules. The researchers also had to determine if any

diseases were triggered by one of these proteins and therefore good

candidates for drugs.

That summer, the scientists had identified only the molecule

made by X1 and its protein target. The biology was proving more

complicated than originally hoped.

As it faced such scientific obstacles, Warp Drive was moving

toward some significant changes. Mr. Borisy, Warp Drive's first

chief executive, returned to Third Rock to help it create new

companies. Dr. Verdine took the helm that July.

Dr. Verdine was among several at the company who began thinking

it should take a different tack: engineering in the lab molecules

that could bind to targets that were already well understood,

rather than waiting to find such molecules in nature and then

working out the diseases they could treat.

Such a change in direction promised to give Warp Drive the

technological platform for developing a range of drugs treating a

variety of conditions. But it would require heavy investment and

might delay the development of the handful of medicines that Sanofi

was in a rush to put into its pipeline.

"Warp Drive wanted to go fishing, but Sanofi couldn't wait to

see what it found," Dr. Zerhouni says.

The doubts reached a boiling point by October 2013, when Dr.

Verdine pulled Dr. Zerhouni into a Massachusetts General Hospital

coffee room. "I want your help to change Warp Drive," Dr. Verdine

says he told him.

Dr. Verdine told Dr. Zerhouni Warp Drive was having trouble

recruiting and retaining staff under the cloud of a potential

Sanofi takeover. For similar reasons, Dr. Verdine went on, Warp

Drive was having trouble persuading other drug companies to

partner.

He bemoaned the terms of the deal negotiated in 2011, when the

public funding markets were in a downturn. The French company had

the option to buy the portion of Warp Drive it didn't own for more

than $1 billion. Now the markets were recovering, and Dr. Verdine

and staff were worried the deal undervalued Warp Drive.

And he described the timeline for discovering new drugs as too

aggressive.

Dr. Zerhouni says he was surprised and troubled by the impact on

Warp Drive's scientific talent. Given the stakes for him inside

Sanofi, he wanted to give the company every opportunity to

flourish. "Let's find a way," he told Dr. Verdine.

The pair went up to a conference room, where they sketched out

on a whiteboard what a restructured collaboration might look like,

making Sanofi the primary partner of Warp Drive but giving it the

runway to join with other companies and eventually go public. Dr.

Zerhouni emphasized getting products was more important to Sanofi

than any technology Warp Drive developed.

While they agreed on the basics, working out the details of what

they wrote on that whiteboard would take another two years.

An initial obstacle, say people involved in the discussions: Dr.

Verdine's leadership of the company. Dr. Verdine wanted to be an

involved father for his brainchild, especially at such a pivotal

moment. He saw that the firm could build the machinery for making

new drugs for myriad previously untreatable disease targets.

In particular, he was interested in a collection of genes called

RAS, involved in cell growth and proliferation. When mutated, these

RAS genes are major drivers of many cancers.

Dr. Verdine asked Harvard to extend his leave of absence from

his academic post. "I'm trying to come up with a drug that will

treat a third of all cancers. I think you would want me to do

that," he recalls telling the university.

Dr. Zerhouni appreciated his partner's commitment. Yet he

worried that Warp Drive needed to apply its findings toward the

practical pursuit of specific drugs, rather than "revolutionizing

the world."

In July 2014, the Warp Drive board agreed on Dr. Verdine's plan

that the firm shouldn't just wait to unravel Nature's mysteries,

but should also use its labs to proactively design molecules that

could target flat proteins like those whose production is

controlled by RAS.

Dr. Verdine eventually agreed to shift to become the company's

chief scientific officer. Warp Drive brought in biotech veteran

Laurence Reid, a former executive at Alnylam Pharmaceuticals Inc.

and Ensemble Therapeutics, as the venture's new chief.

When the partners exchanged proposals in March 2015, a big

sticking point emerged: rights to the drugs that Warp Drive

discovered for Sanofi. The French company sought to retain all the

rights to the promising medicines.

From his industry experience, Dr. Reid figured the startup

couldn't go forward as an independent company and succeed without

some rights to the drugs it found. "Small companies throwing

innovative assets over the wall and then stepping back and hoping

pharma will develop them and send checks is a bit of a fool's

errand," Dr. Reid says.

Dr. Reid says he was "shocked" the partners were so far apart,

and wondered whether he had made a bad decision by taking the Warp

Drive job.

Around Christmas 2015, the two sides negotiated a compromise.

They would narrow their research partnership to some antibiotics

and drugs targeting cancers caused by three different mutations of

RAS. In addition, Warp Drive would be reorganized as a C

corporation so it could raise money and be able to go public. It

could pursue other drugs outside the collaboration and had an

option to split a RAS drug's U.S. rights, while getting royalties

for international sales.

Today, Warp Drive has 57 employees. Last month, the startup

delivered a few dozen bacteria-fighting compounds to Sanofi, which

hopes to turn them into antibiotics to treat drug-resistant

infections.

Dr. Robison, the researcher who found that first promising

bacteria, is optimistic. He says he enjoys working at a lean

startup nimble enough to follow the science wherever it leads, not

slowed by a big company's bureaucracy. At the same time, he

appreciates Sanofi's investment and input and now, agreement to let

the startup's researchers build a stand-alone company.

As in any relationship, Dr. Robison expects new issues to arise

that will require further compromise. "It's kind of like when a

couple renews their vows," he says.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 06, 2016 11:58 ET (16:58 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

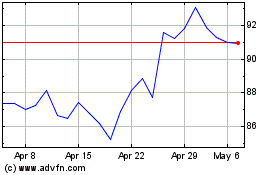

Sanofi (EU:SAN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

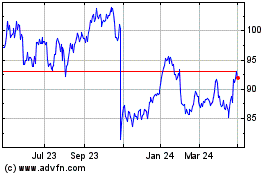

Sanofi (EU:SAN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024