Self-Drive Startup Uses Videogames to Improve Algorithms

December 05 2016 - 5:59AM

Dow Jones News

By Tim Higgins

When entrepreneur Laszlo Kishonti sought a faster way to program

his self-driving car to stay on the road, he turned to a

videogame.

The founder of the Budapest startup used a Microsoft Corp. Xbox

game console to engage the car's computer brain in a

hyper-realistic racing game. The gambit turned out to be a

breakthrough that helped the company speed up development of its

artificial intelligence-based driving technology.

The company, AImotive, which was formerly known AdasWorks, is

one of several teams racing to develop fully autonomous vehicles

that would replace human drivers with software. Mr. Kishonti, with

financial backing from auto-parts supplier Robert Bosch GmbH's

venture capital arm and chip maker Nvidia Corp., aims to have

software available for auto makers as soon as 2021, a deadline set

by several players including Ford Motor Co. and BMW AG. His company

employs more than 100 engineers and programmers, mostly in

Budapest.

Progress in building self-driving cars stems largely from

advances in software that allow computers to learn from experience.

As they drive, such cars collect data from cameras, sonar, radar

and other sensors that helps the computer improve. The greater the

variety of roads driven by these so-called machine-learning

systems, the better they can recognize roadway features, and the

better they can make decisions about how to respond to them.

"Our AI, and all of the AI in the world, learns from the

different scenarios," Mr. Kishonti said in an interview. He

previously founded a company specializing in performance

benchmarking software for high-performance graphics and computing.

"If you show them the same thing every time, it doesn't

improve."

Alphabet Inc.'s Google, for example, has accumulated huge

amounts of data from its 2 million miles of driving on public

roads, and uses the experiences to create countless variations in a

simulation to take the computer through what could happen on the

road.

It is a time-consuming process, and increasingly researchers

have wondered whether hyper-realistic videogames could substitute

for real-world roadways, saving developers time and money. That is

what Mr. Kishonti was hoping when he tried it early this year.

Other autonomous-driving researchers also have experimented with

imagery from videogames. Researchers at Intel Labs and Germany's

Darmstadt University of Technology published a paper detailing

their use of data from Take-Two Interactive Software Inc.'s Grand

Theft Auto videogame to teach a computer vision system to classify

objects along the road. Their idea: help the driving system

distinguish between cars and pedestrians.

"Although games can provide a virtually infinite amount of

photo-realistic training data, a limiting factor is the variety of

scenes in the game," said Stephan Richter, a Darmstadt visual

inference researcher. Grand Theft Auto V "is set in a city similar

to Los Angeles, so extracting data from GTA V will help your

algorithm to learn how driving in a Californian city may look like.

But transferring that knowledge to cities in Europe or Asia can be

tricky."

AImotive took a similar route, using a driving game -- the

company declined to reveal which one -- to help a car understand

how to behave on the road. Think of it as the first week of

driver's ed, but instead of practicing in an empty parking lot, the

system tried to keep the vehicle between the lines on a

computer-generated racetrack -- a lesson applicable to real-world

roadways.

Repetition is key. The team let the car's brain drive through

the videogame until it made a mistake, such as going off the road,

then restarted the game and tried again.

"One of the ways...to train AI [is] you just keep repeating

training steps and eventually get a little further and further" in

learning, said Niko Eiden, AImotive's chief operating officer.

Mr. Eiden described using the videogame to training a car to

steer, accelerate and brake. "Initially the car will always hit the

wall, but after a couple of million tries -- that take only a few

minutes on a regular PC -- it has learned by itself how to drive

around a random track and even accelerates on straight sections --

just like a child learns to walk!"

Mr. Kishonti said after using the videogame for a few weeks his

system had experienced all the variations to be found in the game

world. So the team collected high-definition video of real-world

driving and used the imagery to create videogame-like

simulations.

"We very quickly realized the advantages this kind of a setup

brings and therefore started to develop our own simulator, which we

can properly control and integrate into our development

environment," Mr. Eiden said. "Thanks to our own early experiments,

we now know ourselves exactly what we need and how to use a

simulator to ensure a safer autonomous driving experience in the

future."

Write to Tim Higgins at Tim.Higgins@WSJ.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 05, 2016 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

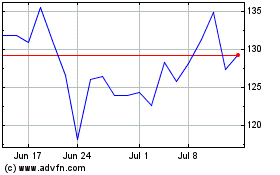

NVIDIA (NASDAQ:NVDA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

NVIDIA (NASDAQ:NVDA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024