A storied but rapidly-shrinking intellectual-property-law

boutique, Kenyon & Kenyon LLP, is moving its practice to

full-service Texas law firm Andrews Kurth LLP, marking the latest

closure from a shrinking national roster of

intellectual-property-law firms.

The deal, to be finalized in the coming days, comes after months

of defections from New York-based Kenyon, which counts companies

including Mattel Inc., Sony Corp. and Volkswagen AG as clients. The

firm employed more than 200 lawyers a decade ago but is down to 55

today in New York, Washington, D.C., and Palo Alto, Calif. All are

joining Andrews Kurth, a 350-lawyer firm that focuses on the

energy, finance and technology sectors.

Founded in 1879, Kenyon is the latest in a string of old-line

intellectual-property-law firms to close over the past several

years. Like Kenyon, many have been absorbed into full-service

firms, largely a reflection of the increasing importance companies

now place on the protection of patents, trademarks and

copyrights.

"We always invented things, but high-tech turns on intellectual

property," said legal consultant Aric Press. Starting around the

late 1990s, he said, "patents became litigated over with no holds

barred and no budgets," turning intellectual property into a

lucrative and coveted practice for larger firms.

Intellectual-property lawyers—both litigators and those who

process patent applications—typically have technical backgrounds,

with many holding advanced degrees in engineering or the sciences.

That has made poaching existing intellectual-property specialists

or scooping up entire boutiques even more attractive to larger

firms trying to get into the practice.

In 2005, for instance, Ropes & Gray LLP acquired

then-prominent intellectual-property firm Fish & Neave. By

then, two other stalwarts in the field, New York's Pennie &

Edmonds and Los Angeles-based Lyon & Lyon LLP, had both gone

bust, with lawyers decamping to other firms. Several smaller

intellectual-property firms have been acquired or dissolved more

recently, including Morgan & Finnegan LLP, whose lawyers joined

Locke Lord LLP in 2009.

Some intellectual-property firms have been able to stay

independent by growing larger themselves, like 370-lawyer Fish

& Richardson, 280-lawyer Knobbe, Martens, Olson & Bear LLP

and Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner LLP, with

350 professionals.

Steven Nataupsky, managing partner of Orange County,

Calif.-based Knobbe, said he thinks stand-alone

intellectual-property firms can survive by being large enough to

employ experts in a range of technical industries and by keeping a

mix of litigators and those who help companies apply for

patents.

"I think those midsize (intellectual-property) firms, if not

balanced, have really struggled," he said.

Andrews Kurth managing partner Robert Jewell said his firm had

been looking to add intellectual-property lawyers to its current

roster of 33 as part of its focus on technology.

Rather than a merger, the deal is structured in a way that has

become popular lately: hire the lawyers but leave the struggling

firm's liabilities behind. Kenyon managing partner Edward Colbert

said the shell of Kenyon would be wound down.

Mr. Colbert said Kenyon, which has helped protect patents for

inventions ranging from the electric trolley and rechargeable

batteries to windshield wipers and videogame consoles, has

weathered multiple swings in the market but could no longer go it

alone.

He said the firm had been affected by some of the latest hits to

patent work, including 2011's America Invents Act, which created a

new method for adjudicating some patent disputes, and a 2014 U.S.

Supreme Court decision that limited patents on abstract concepts,

including software and business methods.

Mr. Colbert has been public about his firm's uncertain future

for several months. He said Monday that since late last year he has

fielded at least a pitch a week for a combination, and that

conversations with Andrews Kurth began about eight months ago.

Despite recent troubles, Kenyon's work has continued to involve

household names. In October a judge sided with a travel website

represented by Kenyon in a trial over whether the company infringed

on social-media giant Pinterest Inc.'s rights to the term "pin."

The firm has long advised the U.S. Olympic Committee and advised

John Oliver, host of HBO's "Last Week Tonight," in trying to

trademark the term "Drumpf" in relation to Donald Trump's run for

the presidency.

The combination with Andrews Kurth won't completely relegate the

Kenyon name to the history books. In New York, Washington D.C. and

California, and in the branding of the intellectual-property

practice, the firm will now be known as Andrews Kurth Kenyon.

Write to Sara Randazzo at sara.randazzo@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 29, 2016 22:35 ET (02:35 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

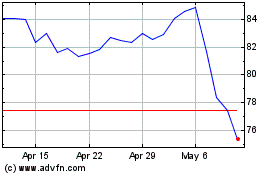

Sony (NYSE:SONY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Sony (NYSE:SONY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024