It was clear John Stumpf, chief executive of Wells Fargo &

Co., was in trouble on Sept. 20, when senators from both parties

castigated him over the bank's sales practices. "It's gutless

leadership…you should be criminally investigated," said Sen.

Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) "This is fraud," said Sen. Pat Toomey

(R., Pa.).

The bank could have been better prepared. Summoned for hearings

in Washington, Mr. Stumpf and other executives didn't answer many

questions from legislators—in public or private—about sales

practices that had led the bank to agree to a $185 million fine and

regulatory enforcement action.

Jon Tester (D., Mont.), said he went into the Senate banking

hearing on Wells Fargo with an open mind but was left "pissed off"

that the CEO didn't answer some questions. The bank didn't try

mollifying the senator likely to be Mr. Stumpf's most dangerous

foe, Sen. Warren. "This is a crisis-management 101 mistake," said

an aide to Sen. Warren.

Even before the hearings, Wells Fargo had been slow-footed in

responding to outrage over employee behavior that included opening

as many as 2 million unauthorized accounts without customer

knowledge. It misjudged the significance of firing 5,300 employees

over five years for related bad behavior, failing to tell its own

board of the number before regulators made it public.

The botched response, a textbook example of how not to handle a

crisis, reached a peak when Mr. Stumpf stepped down Wednesday after

nearly 35 years at the bank and nine years as CEO. It was an

ignominious end to a chief who had overseen Wells Fargo as it grew,

at one point, to be the largest bank in the world by market

value.

At the root of Wells Fargo's crisis-control debacle is an

insular corporate culture, fostered by executives with decades of

tenure, which left it ill-prepared for the tumult that followed its

regulatory settlement, said several former Wells Fargo executives.

Having passed through the financial crisis mostly unscathed, the

bank's brass was largely untested by crisis, these executives

said.

And while Wells Fargo has in recent years become the

third-largest U.S. bank by assets behind J.P. Morgan Chase &

Co. and Bank of America Corp., it tried to stay apart from the Wall

Street crowd. That, and a San Francisco base, helped it operate

largely outside the banking and political limelight.

"They have not projected a sense that how they treated their

customers is an extremely important issue or that they understand

why it is extremely important," said Richard Breeden, a former

Securities and Exchange Commission chairman who has worked with

other companies in crisis. "The recurring themes here seem to be

complacency, arrogance or being disengaged."

Wells Fargo said Mr. Stumpf declined to comment. Wells Fargo

spokeswoman Mary Eshet declined to comment on behalf of other

executives for this article.

Ms. Eshet said: "Immediately following the settlement

announcement we reached out to customers, team members, government

officials, investors and media through various means and we

continue to have active dialogue with all our stakeholders," adding

that "we are focused on ensuring we have the culture, processes and

controls to move the company forward and restore the trust of our

customers and the public."

The bank's failures were especially surprising given the time it

had to prepare. The Los Angeles Times detailed its questionable

sales culture in 2013. Pressure to meet sales goals allegedly led

employees to sign up customers for products they didn't ask for,

including credit cards and bank accounts. In May 2015, the Los

Angeles City Attorney's office, led by Michael Feuer, filed a

lawsuit alleging it pressured employees to commit fraud. Although

the bank denied bad behavior in court filings, it became apparent

to executives there early this year that the legal action would

result in either a trial or settlement, said people close to the

bank.

Wells Fargo's problems escalated soon after the accord was

announced Sept. 8 by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency,

the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and Mr. Feuer's office.

The bank didn't admit or deny wrongdoing in the settlement.

The CFPB, in settlement materials, disclosed the bank had fired

5,300 employees over a five-year period related to the alleged

misdeeds. Wells Fargo responded that the number of affected

employees only represented about 1% of branch employees in each of

the five years. The bank wouldn't say how high up the corporate

chain the firings went, making it seem that few, if any, high-level

executives were affected.

'Scapegoating'

The firings became a lightning rod for outrage and gave rise to

questions of accountability. "This was a systemic problem," Sen.

Jeff Merkley (D., Ore.) told Mr. Stumpf during the Senate hearing,

"and you are scapegoating the people at the very bottom."

The day of the settlement, Mr. Stumpf sent an internal message

to employees, which the Journal reviewed, saying the bank takes

action when it makes mistakes. The chief didn't say he was sorry.

On Sept. 9, in a full-page ad in The Wall Street Journal and other

newspapers, the bank said it took "full responsibility." The ad

wasn't signed by any executive. Mr. Stumpf didn't make any public

statement.

The silence persisted four days. On Sept. 13, the bank took its

first stab at addressing the furor, disclosing it would end

product-sales goals that many employees said drove bad behavior.

Initially, those weren't to be phased out until January 2017.

Later, the bank moved the date to October 2016.

Shortly after, Chief Financial Officer John Shrewsberry, at an

investor conference, said the bank had invested $50 million to

monitor banking activities in response to the problems, including

increasing the number of people engaged in oversight and adding a

mystery-shopper program with an external vendor that conducts more

than 15,000 visits a year to check on sales practices.

As analysts questioned him, Mr. Shrewsberry implied the problem

was over: "It was people trying to meet minimum goals to hang on to

their job. That's my take. It's performance management."

Later that day, in his first interview since the scandal broke,

with the Journal, Mr. Stumpf also focused on the dismissed

employees. That evening, he did his only broadcast interview, with

CNBC's Jim Cramer, in which he tiptoed around the question of his

responsibility.

"To the extent that we don't get it right 100% of the time...if

we don't make that plan, I'm responsible, I'm accountable," he

said. "Anybody else in the company, we all feel when we fall short

of that plan we feel accountable and responsible."

He continued to extol the bank's "cross-selling" efforts, a

longstanding goal to sell as many as eight products to each

customer household. Wells Fargo, Mr. Stumpf said, is "not

abandoning cross sell; we love cross sell."

The next morning, on Sept. 14, he spoke by phone with Wells

Fargo's biggest investor, Warren Buffett, whose Berkshire Hathaway

Inc. owns about 10% of the bank. Mr. Buffett told Mr. Stumpf he

didn't think the CNBC interview went well, Mr. Buffett told a CNBC

reporter on Sept. 29, CNBC reported.

Mr. Buffett said he thought the problem was much bigger than Mr.

Stumpf seemed to think it was, and public reaction to it should not

be measured by the size of the fine, the channel said. Mr.

Buffett's assistant, Debbie Bosanek, said the CNBC report was

accurate and that Mr. Buffett wouldn't expand on it.

A few days later, the bank learned the Senate Banking Committee

would call Mr. Stumpf, and it retained law firm Gibson, Dunn &

Crutcher LLP for advice.

With a week to prepare, Mr. Stumpf met repeatedly with Gibson,

Dunn partner Michael Bopp, who with his team prepped the CEO. The

work focused on making sure Mr. Stumpf wouldn't "get rattled" by

lawmakers and "inflame the situation any more than it is," said a

person familiar with the discussions. The person said Mr. Stumpf

and the lawyers felt limited in what the CEO could say given

continuing investigations.

Outside communications strategists weren't included in all the

sessions, sometimes known as "murder boarding." The overarching

message was that the CEO wouldn't "win" and would likely be

attacked from all angles, the person said.

The atmosphere grew heated, with the Journal reporting the

Justice Department had opened an investigation. Timothy Sloan, the

bank's chief operating officer, and Anita Eoloff, a Wells Fargo

government-relations executive in Washington, headed to Capitol

Hill. They met with staff representing Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown, the

banking committee's ranking Democrat, said people familiar with the

meeting.

Unanswered questions

Mr. Sloan tried to respond to questions as Ms. Eoloff took notes

on those he couldn't answer, said one of the people. When did Mr.

Stumpf first learn of the sales-practices problems? Mr. Sloan said

it was some time in late 2013, without offering specifics. What was

the specific timeline of when and how the bank informed regulators

of the problems? Again, Mr. Sloan didn't offer specifics.

That frustrated Sen. Brown's staff, the person said. They tried

a simpler question: Who was the consultant that did the independent

study for Wells Fargo that calculated that 5,300 people were fired?

Mr. Sloan said he was "contractually barred" from answering.

On Sept. 16, the Journal reported it was PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Three days later, Ms. Eoloff reported to Sen. Brown's staff that

PwC was the contractor—one of the few follow-ups the office

received, the person said. A PwC spokeswoman declined to

comment.

When Mr. Stumpf finally appeared in the Dirksen Senate Office

Building for the hearing, he, too, had few concrete answers. He

repeatedly said decisions about pay for top executives— a new

element in the crisis—were matters for the board, not him, to

discuss. He maintained the sales problems didn't show a deeper

cultural flaw or constitute "massive fraud."

Sen. Tester met days before the hearing with Mr. Sloan, the COO.

He was surprised Wells Fargo "never got back to me with any

answers" to questions from that meeting.

That day, Sen. Tester was willing to delay judgment until he

heard Mr. Stumpf's side of the story. Then Mr. Stumpf waffled in

the hearing. "It's been going on for five years, and he walks in in

front of the Senate Banking Committee and he doesn't have any

answers for this problem?" Sen. Tester said in an interview. "By

the time the questioning got to me, I was pretty well pissed

off."

One flashpoint involved a decision about two months before the

settlement was announced. That's when Mr. Sloan met with Carrie

Tolstedt, the former retail-banking head whose unit was responsible

for the bad behavior. Mr. Stumpf and Mr. Sloan had decided the bank

needed to make a leadership change to accelerate revamping that

part of the business.

After the meeting, Ms. Tolstedt, a 27-year Wells Fargo veteran,

decided to retire at year's end. Mr. Stumpf told the board of Ms.

Tolstedt's decision, said people familiar with the matter. The

board also learned in June that the CFPB settlement was looming,

the people said. By retiring, Ms. Tolstedt would leave with around

$100 million in compensation earned over time at Wells Fargo.

Sen. Brown demanded of Mr. Stumpf: "So 5,300 team members

earning perhaps $25,000, $30,000, $35,000 a year have lost their

jobs while Ms. Tolstedt walks away with up to $120 million."

Days after the Senate hearing, the House Financial Services

Committee announced it, too, would call in Mr. Stumpf.

The bank's board, without Mr. Stumpf, met most of that Sunday

afternoon at the Midtown Manhattan office of Shearman &

Sterling LLP. It had just hired the law firm to do an independent

investigation of the sales-practices problem, about three years

after management brought the issue to directors' attention.

The board decided, at Mr. Stumpf's recommendation before the

meeting, that he would forfeit equity, awarded but unvested, of $41

million. It also took away his 2016 bonus and salary during the

investigation. The board clawed back about $19 million of unvested

equity from Ms. Tolstedt and insisted she leave immediately. Ms.

Tolstedt couldn't be reached for comment.

Two weeks later, Mr. Stumpf told Mr. Sloan he was becoming too

much of a distraction and would retire. He officially informed the

board Wednesday afternoon.

Brody Mullins, James V. Grimaldi and Anupreeta Das contributed

to this article.

Write to Emily Glazer at emily.glazer@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 13, 2016 15:05 ET (19:05 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

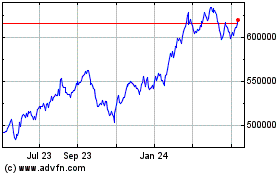

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

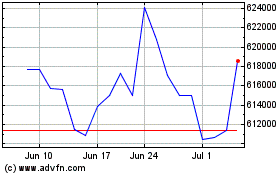

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024