By Jason Zweig

Stock splits are going extinct.

So far in 2016, only five companies in the S&P 500 stock

index -- and only 63 among more than 10,100 U.S. companies tracked

by S&P Dow Jones Indices -- have split their shares. This year

is on track to be the third-lowest for stock splits in modern

history, behind only 2009 and 2010, when companies were too

traumatized by the financial crisis to dare lowering their share

prices.

Share prices that look like typographical errors -- Berkshire

Hathaway's, around $217,000; NVR, the home builder, around $1,640;

Priceline Group, about $1,470; Alphabet, the parent of Google, over

$800 -- are becoming the norm. The days of giving 100 shares of

stock as a confirmation or bar mitzvah or graduation gift may be

doomed.

But I am not here to lament the demise of the stock split. In

fact, that is good news. It is a sign that the investing world may

finally be learning the distinction between the price of a stock

and the value of a business.

In a typical 2-for-1 split, a company doubles the number of its

shares outstanding while halving the per-share price. That is the

stock-market equivalent of exchanging one dime for two nickels. You

end up holding twice as many units each worth half its former

price. You would be foolish to think that makes you richer.

Back in the days when stock tickers went clickety-clack and

stockbrokers were human beings rather than websites, it was cheaper

to trade in "round lots" of 100 shares than "odd lots" of less than

100.

And during the internet bubble, companies with levitating stock

prices could get another boost just by announcing a stock split,

which traders erroneously regarded as a sure sign of future

gains.

But today, online discount brokers such as Fidelity Investments

or Charles Schwab charge commissions of less than $10 a trade

regardless of how much stock you buy or what the share price

happens to be.

As companies stop splitting, the average price of an S&P 500

stock, according to Credit Suisse, has risen to a near-record $86 a

share -- after decades of remaining in a range between $25 and $45.

(Adjusted for inflation, average share prices fell by more than 90%

between 1933 and 2007 -- a trend that has sharply reversed since.)

The average share price of companies in the small-stock Russell

2000 index, by contrast, has risen only to about $29.

Index funds, those autopilot portfolios that are run to minimize

costs, own proportionately more of large stocks than small

stocks.

Unlike individuals, funds generally pay commissions based partly

on how many shares they trade, so it is generally more expensive

for funds to buy and sell a stock after it splits. These big funds,

not individuals, are the investors most companies cater to

nowadays.

Some still say that splitting is a signal of good health.

When Louisville, Ky., beverage company Brown-Forman announced a

2-for-1 split in May, its chief executive, Paul Varga, said the

move "reflects the company's confidence in our ability to

sustainably grow our sales, earnings and cash flow over the long

term."

"There's no compelling business case to doing it," says Robert

M. Knight Jr., chief financial officer of Omaha-based Union

Pacific, which last split, 2-for-1, in 2014. "It's more of a feel,

kind of a subtle message of confidence that maybe your stock is

going to continue to rise."

But even that sort of ambivalent support is dwindling.

Home Depot split its stock in eight of the 11 years from 1989

through 1999, cumulatively turning each one of its shares into more

than 30. It hasn't done a split since and has no plans to do

another, says its head of investor relations, Diane Dayhoff.

A split "wouldn't change the intrinsic value of the company and

doesn't provide any real benefit," Ms. Dayhoff says, while

administrative and registration costs would likely run into the

hundreds of thousands of dollars. "We have to sell a lot of hammers

to make that up," she says.

Thomas Gayner is co-chief executive of Markel, an insurance

company whose share price brushed $930 this past week. "If you and

I together bought some commercial real estate for $1 million," he

asks, "would it matter whether we divided it so we each held one

share at $500,000 apiece or 500 shares at $1,000 apiece?"

He adds, "we want shareholders who focus on the investment

itself, rather than on the currency it's denominated in."

Even Mr. Gayner admits, though, that a high stock price still

has a vestigial allure. If Markel goes above $1,000 a share, he

says, "I'll probably take my wife out to dinner." Then, catching

himself, he adds with a laugh: "But I won't use Markel stock to pay

for it."

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 01, 2016 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

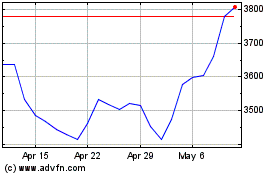

Booking (NASDAQ:BKNG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Booking (NASDAQ:BKNG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024