By Michael Wursthorn

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (July 28, 2017).

Wall Street brokerages have been selling billions of dollars in

loans backed by stocks and bonds, a trend that yields lucrative

fees for the firms but poses risks for borrowers.

While banks don't always report these loans in the same way,

these securities-backed loans total at least $100 billion for the

biggest brokerages -- up exponentially since the financial crisis

-- with several billions of dollars of additional debt held at

smaller brokerages, banking analysts estimate.

Executives at Morgan Stanley earlier this month highlighted

these loans to individuals as a big growth area and revenue driver,

saying the loans helped expand the bank's overall wealth lending by

about $3.5 billion, or 6%, in the second quarter. On Thursday,

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. took a step toward expanding its

securities-based lending business through a new partnership with

Fidelity Investments.

The loans work a lot like margin loans. Brokerages lend against

the value of an investor's portfolio. But unlike margin lending,

customers don't use the debt to buy more securities. Brokerage

executives say the loans can help clients avoid selling assets. The

client can get cash without shifting their investments; they also

avoid potentially locking in losses or incurring taxable gains, or

missing out on future stock market gains. Clients are also able to

borrow money at relatively low interest rates because the loans are

secured.

"Securities based loans can be a valuable financial planning

tool for appropriate clients," a Morgan Stanley spokesman said.

Critics worry that the surging stock market has made investors

numb to the risks of borrowing against their investments -- a

scenario that has played out before. In the runup to the Great

Depression, the dot.com bubble of 2000 and the financial crisis,

investors binged on margin debt that proved perilous when stocks

tumbled.

Investors using these loans now could face a similar fate if

markets tank and the value of their collateral shrinks, prompting

the bank to demand repayment. If the margin call isn't met, the

securities backing the loans are sold and the borrower is

responsible for any remaining balance.

For brokerages, these loans have become a reliable source of

revenue in the years since the financial crisis, as firms have

begun moving from a business model of charging commissions for

trading to a system of fees based on assets under management. The

loans themselves help brokers retain these assets because customers

don't have to sell stocks and other securities when they need cash.

These loans have also become a big factor in brokers'

compensation.

Several Merrill Lynch brokers said they have asked longstanding

clients to open a securities-backed line of credit to help them hit

bonus hurdles, assuring that clients wouldn't need to use it or pay

any fees for opening it. Merrill brokers receive continuing

payments for getting clients to tap credit lines, and those loan

balances contribute to year-end bonus calculations, people familiar

with the matter said.

Brokerage executives have said the longer a client has one of

these loans tied to their account, the more likely they are to use

it.

"We were dramatically pushed to put these on all of our client

accounts, " said Steven Dudash, a former Merrill Lynch broker who

has been managing his own investment-advisory firm since 2014.

"Whenever you're product-pushing, it's not in the client's best

interest."

Merrill representatives say its brokers offer these loans to

clients in a responsible manner, including disclosing the risks and

fees.

"If people need the money, they should sell securities," said

Terrance Odean, a professor of finance at the Haas School of

Business at the University of California, Berkeley. "It's very

risky to take a leveraged position in the market, and I don't think

people are thinking about it that way."

Wells Fargo & Co. recently changed practices around how

brokers pitch lending products. Starting this year, Wells Fargo

stopped offering brokers bonuses tied to how many loans, including

securities-backed debt, they opened for clients, executives of the

bank have said.

As of the end of 2016, clients of Bank of America Corp.'s wealth

unit, which includes Merrill Lynch and private bank U.S. Trust, had

some $40 billion in such loans outstanding, up 140% from 2010.

Morgan Stanley's customers had $30 billion in these loans, more

than double from 2013. UBS Group AG and Wells Fargo also have made

billions of dollars in such loans, people familiar with those banks

said.

Morgan Stanley's finance chief, Jonathan Pruzan, said while

discussing earnings this month that the bank expects more clients

to take out loans in the months ahead. "That's been a real key

driver of our wealth business," he said.

The growth of securities-backed loans has drawn the attention of

regulators, who have questioned the brokerages' marketing and sales

efforts as well as the suitability of the loans.

Merrill opened more than 121,000 such loan accounts between 2010

and 2014 with more than $85 billion in total credit extended,

according to a Financial Industry Regulatory Authority settlement

order last year. In the matter, Finra alleged that Merrill didn't

fully explain the risks of securities-backed loans and used risky

or concentrated investments as collateral.

Merrill settled its case without admitting or denying the

allegations. Merrill reported its securities-lending oversight

lapses to Finra initially and cooperated with the regulator's

inquiry, according to Merrill representatives. They said the firm

has improved its procedures.

In another regulatory action, the Massachusetts securities

watchdog last year accused Morgan Stanley of developing a sales

program that encouraged brokers to pitch these loans regardless of

whether clients needed them. Brokers involved in the incentive

program were given scripts coaching them to offer securities-backed

loans to clients who said they needed to pay taxes or cover

expenses for a wedding or a graduation party, or if they mentioned

"purchasing a luxury item like a car or yacht," according to the

regulator.

"It's not healthy for the industry," said William Galvin,

Massachusetts' top securities regulator, who has been investigating

how firms motivate brokers to push these loans. Brokerages "should

be more concerned about this," he said, "but they're in favor of

competition and seeing who can get more loans."

Morgan Stanley agreed to a $1 million settlement with the

regulator in April without admitting or denying wrongdoing. A

Morgan Stanley spokesman said Massachusetts found no evidence that

any clients were harmed or that any of the loans were unsuitable or

unauthorized.

"We have taken steps to strengthen and clarify our policies and

controls around such initiatives," he said.

Write to Michael Wursthorn at Michael.Wursthorn@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 28, 2017 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

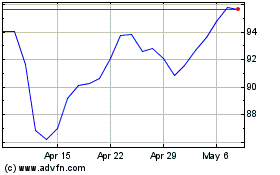

Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

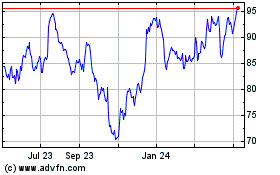

Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024