SEATTLE—Boeing Co. started to make money on each 787 Dreamliner

it delivers just this spring, but thanks to a unique accounting

strategy the jet has been fattening the aircraft maker's bottom

line for years.

Boeing is one of the few companies that uses a technique called

program accounting. Rather than booking the huge costs of building

the advanced 787 or other aircraft as it pays the bills,

Boeing—with the blessing of its auditors and regulators and in line

with accounting rules—defers those costs, spreading them out over

the number of planes it expects to sell years into the future. That

allows the company to include anticipated future profits in its

current earnings. The idea is to give investors a read on the

health of the company's long-term investments.

Boeing calculates its Dreamliner earnings based on 10-year

forecasts of supplier contracts, aircraft orders and options,

productivity improvements, labor contracts and market conditions,

which are reviewed by its auditors. The company, which delivered

its first Dreamliner in 2011, estimates it will sell 1,300

Dreamliners over the 10 years ending in 2021. So far, it has

delivered nearly 500 of them.

The problem, analysts and other critics say, is that Boeing's

approach stretches its profit per plane on the Dreamliner into such

a distant and uncertain future that it isn't clear if it will ever

recover the nearly $30 billion it has sunk into producing the plane

and validate years of projected profits.

"Any estimating process that looks this far out in the future

and has this many moving parts and assumptions is almost certainly

destined to be wrong," said Carter Copeland, aerospace analyst at

Barclays Capital.

Boeing rivals Bombardier Inc. and Airbus Group SE use a

different accounting system. Both aircraft makers report losses on

new aircraft programs as they accrue during development and

production.

If Boeing similarly accounted for its planes, including the 787,

the $22.1 billion in commercial-aircraft group earnings it has

booked since 2012 would be an $1.85 billion loss, its disclosures

say.

The Securities Exchange Commission, which has broadly supported

Boeing's accounting technique in the past, began investigating

whether the company overstated elements of its accounting for the

787 project, people familiar with the matter revealed early this

year. Details couldn't be learned. Such investigations often take

years.

An SEC spokeswoman declined to comment.

Boeing, which hasn't confirmed or denied the investigation, has

defended its accounting—which complies with generally accepted

accounting principles—and says its profit expectations are

realistic. Though the Dreamliner has proved much more costly to

make than expected, the company says its cost for each 787 fell

below the selling price in the second quarter as it reaped greater

production efficiencies.

Deloitte & Touche LLP, Boeing's auditor, said it couldn't

comment on client matters.

To recover production, tooling and other one-time costs of the

Dreamliner program, Boeing's costs would have to fall fast enough

and the price it charges airlines remain high enough for the

company to make an average of $36 million profit on each of the

next 800 Dreamliners it manufactures, including 233 planes that

haven't been sold. The list price of a 787 is between $225 million

and $306 million, but airlines typically negotiate big

discounts.

If Boeing and its auditors determined that it couldn't recover

its costs over the life of its forecast, accounting rules would

require the company to declare that the program was operating at an

overall loss, and force it to take a write-off.

"They have to defend that 787 curve very tightly," said Robert

Spingarn, aerospace analyst at Credit Suisse. "You can either find

more profit...or go out and change your cost structure to get you

back on the curve."

"We continue to believe [the 787] will be a significant

contributor to Boeing's success for decades to come," Boeing

said.

Boeing, which initially expected to invest $5 billion to design

and build the carbon-fiber Dreamliner, ended up spending 10 times

that sum, after holdups and hurdles stemming from extensive

outsourcing and design issues. Compensating customers for delays

and the bargain-basement prices Boeing used to spur sales weighed

on its per-plane revenue.

Boeing originally estimated its average cost per plane would be

around $40 million, excluding engines and custom interiors, say two

former Boeing employees. Today, the 787's average production cost

is more than double that, say analysts, a sum that is only now

coming in line with the current unit cost per plane.

Boeing declined to disclose its original target for the plane,

but said its business case "anticipated correctly its overwhelming

market success."

Though it is facing a slowdown in orders for twin-aisle jets

like the 787, Boeing assumes it will continue making a dozen 787s a

month over the next decade, most of them larger and pricier

versions of the jet, and that its production costs will drop over

time. Boeing has said it is weighing the idea of making as many as

14 of the planes a month later in the decade.

The International Institute for Strategic Leadership, an

independent group of academics and executives that includes

analysts and former Boeing consultants, recently concluded that

Boeing wouldn't be able to bring down the costs of each 787 without

squeezing suppliers and would face significant pressure from Airbus

to lower the price.

In the end, whether the 787 delivers the profits Boeing has

promised may depend on how many planes it uses to average out its

costs and profits. Boeing could choose to expand that block beyond

the current 1,300 jets.

"I don't think we'll ever know because the block size will not

be static," said Mr. Copeland of Barclays.

Boeing says decisions about the block size are based on its

reasonable expectation of future sales.

Aruna Viswanatha contributed to this article.

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon.ostrower@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 04, 2016 08:05 ET (12:05 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

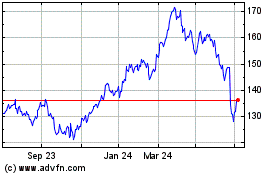

Airbus (EU:AIR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

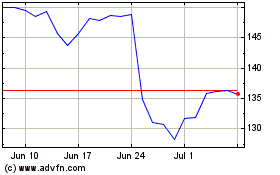

Airbus (EU:AIR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024