In a quiet office in suburban Greenwich, Conn., 45 minutes from

bustling Wall Street, a little-known firm called Timber Hill LLC is

trying to grab a bigger share of the world's foreign-exchange

trading business.

Timber Hill's head of foreign-exchange trading, 28-year-old Matt

Lauria, hopes to challenge Wall Street's banks by using high-speed

technology to pump out currency prices at extreme speeds, thus

quickening transactions for hedge funds and other computer-driven

investors looking for cheaper, more discreet trading.

The firm is one of many electronic upstarts bringing rapid-fire

automated trades to the global currency markets, where such

high-frequency trading has been slow to catch on. Burned by bad

bets on mortgages and risky derivatives during the financial

crisis, some Wall Street banks and investors are looking at the

relatively stable foreign-exchange market to generate income. That

has fueled a three-way race to build faster systems, a race between

such Wall Street giants as Deutsche Bank AG, the biggest

currency-trading venues like brokerage ICAP PLC's EBS, and smaller

market participants like Chicago's Allston Trading LLC; Currenex,

owned by State Street Corp.; and Timber Hill, a unit of Interactive

Brokers Group.

In seeking to offer easier ways to make money from currency

trading to more investors, including individual players too small

for Wall Street, these players are tussling for greater clout over

the $4 trillion-a-day global foreign-exchange industry.

"There's been a seminal change in how investors are allocating

cash to high-frequency trading," says John Netto, founder of New

York-based M3 Capital LLC, a high-frequency trading firm.

"Investors' desire for liquidity and transparency is now driving

how investments are structured. It's now investors who are

controlling the terms."

The move to high-speed currency trading is gathering steam.

High-frequency trading accounted for roughly 30% of all

foreign-exchange flows, as of 2010, compared with 13% in 2004,

according to Boston-based consulting firm Aite Group. (By contrast,

66% of global stocks trading is high frequency.) About 85% of the

currency market's growth in volume from 2007 to 2010 came from

financial institutions like hedge funds rather than Wall Street's

traditional bank currency dealers, thanks partly to high-frequency

traders, say analysts at Brown Brothers Harriman, based on data

from the Bank for International Settlements.

Hotspot FX, a small currency-trading platform owned by Knight

Capital Group Inc. that serves hedge funds and high-speed traders,

saw around $1.3 trillion in volume last month, a 72% jump over the

same month last year. "We've really had some exceptional growth in

the last two years," says director William Goodbody.

Things could heat up further. While new financial regulations

and last May's flash crash in U.S. stocks have intensified scrutiny

of high-frequency trading, efforts on Capitol Hill to make

derivatives safer could push some foreign-exchange options trading

onto electronic systems, possibly giving high-speed trading a

boost, bankers say. Currently, most high-frequency currency trading

involves actual currencies, not derivatives, which are mostly

traded over the counter. Aite Group expects the proportion of

currency trading that is high frequency to jump 41% this year and

next, compared with a paltry 2% rise for stocks.

As nonbank currency-trading venues have proliferated, prices

have become more easily available and once-distant market

participants have begun trading with each other. That's eroded the

value of traditional Wall Street middlemen, whose profit margins in

foreign exchange have narrowed. And with market participants now

less able to gain a trading edge through privileged access to

prices, they have moved into high-speed systems to gain a timing

advantage instead.

A former currency derivatives trader in Royal Bank of Scotland

Group PLC's Greenwich office, Lauria left the bank two years ago to

beef up Timber Hill's presence as a high-frequency market maker in

foreign exchange. (Market makers are middlemen who buy and sell to

facilitate trading, while trying to profit on their trades.) Until

about five years ago, Timber Hill, which was formed in 1982,

focused mostly on stock options.

"My first day, it was so quiet," Lauria recalls. "At RBS, in the

foreign-exchange options group, people were constantly shouting

over the boxes to their brokers to do their trades. When I got

here, it was subdued. It had to do with everything being done

electronically."

After checking his profit-and-loss figures each morning around

7, Lauria these days spends much of his time figuring out how to

adjust his technology to speed up Timber Hill's ability to shoot

out prices as fast as possible.

Speed, anonymity and liquidity, which is the ability to buy and

sell easily, are the top priority for today's currency traders. In

the past, a hedge fund might approach a single Wall Street bank to

trade $3 million and receive a bid/ask spread, which is the gap

between what sellers are offering and buyers are willing to pay, of

around 2 or 3 pips, which are tiny increments of currency prices.

Banks would then offload their risks by trading with rivals in an

interbank electronic trading market.

Now, with direct access to an electronic trading system, the

hedge fund can trade $10 million with a dozen banks at once at a

spread of one pip. Even better, the hedge fund doesn't need to

spend cash setting up trading links with various banks, which often

only want to serve bigger investors.

Some observers complain that high-frequency and so-called

algorithmic traders make life harder for other participants in the

currency markets, especially Wall Street's big banks.

One worry: High-speed trading may make currencies more volatile

during times of market stress. Sharp moves can hurt smaller

investors who can't react as quickly.

With so many computer-generated trades "programmed in" every

day, investors may develop an exaggerated sense of the market's

liquidity, which means any sharp withdrawal of liquidity hurts all

the more, says a top Wall Street foreign-exchange banker. An

analogy is the difference between a normal person and a

manic-depressive, this source says. "A normal person gets happy or

sad, but a manic depressive person can get suicidal."

Take the Japanese yen. A few days after Japan's 9.0-earthquake

and tsunami last month, the yen soared 4.6% against the dollar

within minutes after 5 p.m. in New York, a time when few investors

around the globe are at their seats. Many blamed the March 16 surge

on a freak combination of stop-loss orders, which automatically buy

or sell when currencies hit extreme levels, and an unwinding of

currency derivatives trades. But others pointed to the possible

role of computer-driven trading.

"The move was swift and illiquid," wrote J.P. Morgan Chase &

Co.'s Michael Grise in an e-mail to clients on March 16 that was

obtained by the Wall Street Journal. "There was very little active

customer flow, the bulk of our volume was standing stops and

algorithmic traders on the machines."

Other observers dismiss such concerns, saying investors

generally have a poor understanding of high-frequency and

algorithmic trading strategies, which often involve nothing more

than doing the same trade but faster. Fears of high-speed trading,

according to this view, are only the latest version of a long-held

suspicion of hedge funds.

M3 Capital's Mr. Netto says computer-generated trading may

intensify minor moves at key times, such as the release of a major

economic report, since traders are using programs to react. But, by

and large, such effects are negligible for the currencies.

The benefits far outweigh the costs, says Timber Hill's Lauria.

"In the past, there would have been 10 major banks making markets

in FX, and all it took then to cause a crash was 10 people to throw

up their hands. Now, because you have so many market makers out

there, in order to have a crash you have to have 1,000 people

saying, 'Hey, I'm not willing to buy,'" he says.

"If you increase the number of players, you're going to have

better markets that are more resilient," he says.

-By Neil Shah; Wall Street Journal; 212-416-2619;

neil.shah@wsj.com

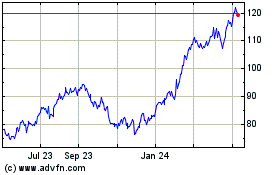

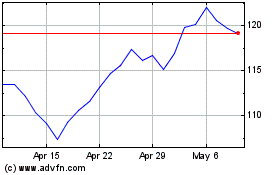

Interactive Brokers (NASDAQ:IBKR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Interactive Brokers (NASDAQ:IBKR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024