John Gutfreund died Wednesday at age 86, marking the formal end

of an era on Wall Street when swashbuckling bond traders made huge

bets using house money.

A cigar-chomping former bond trader, Mr. Gutfreund spent 38

years at Salomon Brothers, once a feared powerhouse on Wall Street

that he boasted was "the greatest trading organization the world

has ever known."

Mr. Gutfreund transformed Salomon into the dominant force in the

Treasury securities market, overseeing a trading floor the size of

a football field. Under his helm, Salomon made big wagers using the

firm's cash and sold the first mortgage-backed bonds. He turned

Salomon from a private partnership to a publicly traded firm.

Business Week dubbed him the "King of Wall Street."

But Mr. Gutfreund's career at Salomon came to a sudden halt in

1991 amid a Treasury-note auction scandal, one of the largest ever

on Wall Street.

In one instance, Salomon controlled an astonishing 94% of the

two-year Treasury notes sold to competitive bidders at an auction,

enabling Salomon to corner a good portion of the market, violating

Treasury rules.

He became personally embroiled in the scandal when Salomon

revealed that he had been told the firm had made an illegal bid in

a Treasury-note auction, but didn't report the wrongdoing to the

government for months.

Nestled in his elegant 43rd-floor office in 7 World Trade Center

overlooking the Hudson River, Mr. Gutfreund initially sought to

tough it out. Dressed in his trademark dark suit and white shirt,

he told top executives at a closed-door meeting shortly after the

disclosures: "I'm not apologizing for anything to anybody.

Apologies don't mean s—. What happened, happened."

He soon was pressured to resign, following two calls from the

furious head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York who had

demanded action.

It was one of the swiftest falls for a leading Wall Street chief

executive: Just weeks earlier, Salomon had reveled in record

earnings, driven largely by bond-trading profits.

Warren Buffett, the billionaire investor who had held a large

Salomon stake, stepped in and helped lead the firm out of the

scandal. The reality of the firm's business strategy later was

crystallized in a homespun way at a Salomon board meeting.

Charles Munger, Mr. Buffett's close associate and then a Salomon

director, likened Salomon's trading arms to a "gambling casino with

a restaurant out front."

The casino—the group doing proprietary trading for the house—"is

the thing we really want because it makes a lot of money," he told

directors. "And we're happy to have the restaurant"—customer

businesses such as stock and bond trading and investment

banking—"as long as it doesn't cost too much."

Salomon in 1992 struck a $290 million accord with the Securities

and Exchange Commission and other government agencies to settle

allegations relating to the bidding scandal.

Salomon never was the same, and later was absorbed into what

became Citigroup Inc. In his later years, Mr. Gutfreund cut a far

lower profile, working for a time as a senior adviser at C.E.

Unterberg, Towbin, a boutique firm.

Born in Scarsdale, N.Y., Mr. Gutfreund attended Oberlin College,

received a degree in English and served in the U.S. Army in Korea.

He joined Salomon in 1953 after his Army service as a trainee in

the statistical department, clerked in the firm's municipal-bond

department and later became a trader. Even after he rose into

management, he would spend hours smoking cigars and trading

securities.

Under Mr. Gutfreund's helm, Salomon traders could make huge

amounts of money—often far exceeding what he earned.

Mr. Gutfreund also helped oversee the rise of oil trading on

Wall Street.

Through it all, Mr. Gutfreund presided over bawdy antics of some

of Salomon's traders. Some of these were depicted in the

best-selling book "Liar's Poker," which irked him. In the book,

former Salomon bond salesman Michael Lewis painted an unflattering

picture of Salomon sticking certain clients with bad bonds on

occasion, among other things.

At Salomon's 1990 annual meeting, Mr. Gutfreund admitted that

the book had made the firm "a laughingstock" and caused tension

with clients.

At the meeting, Mr. Gutfreund said he never met Mr. Lewis, and

said the book bore "no relation to reality." The book

"systematically attempted to say we ravaged our customers. It

didn't make much sense," he said. "We may have been stupid, but we

have been honorable in dealing with our customers."

In an unusual diversion from the meeting's Wall Street

solemnity, Mr. Gutfreund also critiqued other financial books. He

called "Barbarians at the Gate"—the account of the mammoth RJR

Nabisco Inc. takeover—a "pretty good book."

One passage in "Barbarians" describes Salomon pulling out of the

deal because its name wouldn't be on the preferred side of a

planned advertisement.

That passage was "a gross oversimplification," Mr. Gutfreund

said. "We had major reservations about other aspects of the

deal."

Outside of work, Mr. Gutfreund was very fond of Tony Bennett and

his music and his painting. Mr. Bennett used to visit Mr.

Gutfreund's apartment in New York to sing.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 09, 2016 17:05 ET (22:05 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

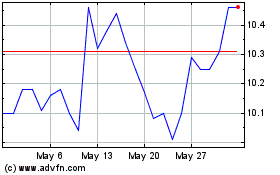

Pacific Current (ASX:PAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From May 2024 to Jun 2024

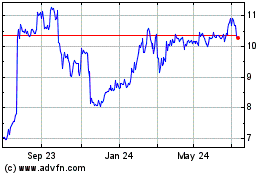

Pacific Current (ASX:PAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2023 to Jun 2024