By Jacob Bunge and Ruth Bender

For years, scientists at Monsanto Co. worked closely with

outside researchers on studies that concluded its Roundup

weedkiller was safe.

That collaboration is now one of the biggest liabilities for the

world's most widely used herbicide and its new owner, Bayer AG,

which faces mounting lawsuits alleging a cancer link to

Roundup.

Plaintiffs' attorneys are putting Monsanto's ties to the

scientific community at the center of a series of high-stakes suits

against Bayer. Since the German company acquired Monsanto last

June, two juries in California have sided with plaintiffs who have

lymphoma and blamed the herbicide for their disease. Bayer's shares

have fallen roughly 35% since the first verdict.

In both cases, plaintiffs' attorneys argued that Monsanto's

influence on outside studies of Roundup's active ingredient tainted

the safety research. The attorneys obtained certain Monsanto emails

showing outside scientists asking the company's scientists to

review their manuscript drafts, and Monsanto scientists suggesting

edits.

Gary Kitahata, a member of a jury that ordered Bayer to pay

$289.2 million to a former California groundskeeper with

non-Hodgkin lymphoma last August, said Monsanto's interaction with

outside researchers played an important role in jurors'

deliberations. He recalled being struck by emails allegedly dealing

with "things like ghostwriting, influencing scientific studies that

were done." A judge later reduced the award, which Bayer is

appealing, to $78.5 million.

Last month, a federal jury in San Francisco awarded $80.3

million to another man with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who had used

Roundup, a verdict Bayer also plans to challenge. Another trial is

under way in Oakland, involving two more of the 11,200 U.S.

farmers, landscapers and others who have filed suit, threatening

product-liability costs at Bayer for years to come.

Bayer said hundreds of studies and regulatory decisions across

the globe show the active ingredient in Roundup, called glyphosate,

is safe and isn't carcinogenic. Regulators in the U.S. and abroad

have continued to approve its use, in some cases after having gone

back and taken another look at research criticized by plaintiffs'

attorneys.

"Plaintiff lawyers have cherry-picked isolated emails out of

more than 20 million pages of documents produced during discovery

to attempt to distort the scientific record and Monsanto's role,"

Bayer said. A spokesman said the documents at issue relate only to

secondary reviews of past research, not to the original science. He

added that the outside scientists have stood by their

conclusions.

In the U.S., Roundup has become almost as fundamental to farming

as tractors. American farmers use it or other glyphosate-based

herbicides on the vast majority of their corn, soybean and cotton

acres, making it a factor in American agriculture's steadily rising

productivity.

Monsanto developed the chemical decades ago and later introduced

crops genetically engineered to survive being sprayed with it,

driving what is now a more than $9 billion seed business for Bayer.

Annual sales of glyphosate herbicides, including by competitors,

total around $5 billion, according to Sanford C. Bernstein.

Despite their regulatory acceptance, the herbicides have faced

growing resistance, especially since a 2015 decision by the

International Agency for Research on Cancer, a World Health

Organization unit, classifying glyphosate as likely having the

potential to cause cancer in humans. In January, a French court

banned a Roundup product with the ingredient, even though it had a

European Union seal of approval.

Costco Wholesale Corp. recently pulled Roundup herbicides from

its stores, according to an executive of the retailer. Certain

cities in California, Florida, Minnesota and elsewhere have

forbidden glyphosate weedkillers on municipal property. Other

farm-state lawmakers have defended the herbicides.

The attack on Monsanto's role in research that deems Roundup

safe is led by Baum Hedlund Aristei Goldman PC, a law firm

representing more than 1,400 plaintiffs. It has selectively

released hundreds of company emails obtained through legal

discovery and put many of them on its website.

"These documents provide evidence that Monsanto's been actively

engaged in manipulating the science regarding glyphosate's

carcinogenicity," said Michael Baum, the firm's managing

partner.

One document cited by plaintiffs' attorneys is a 2000 email that

Monsanto's Hugh Grant, later the company's chief executive, sent

following the publication of a paper upholding Roundup's safety.

"This is very good work, well done to the team," he wrote to

Monsanto scientists.

They weren't the paper's authors. Outside scientists were. An

acknowledgements section cited Monsanto researchers as having

provided scientific support. They had reviewed the text and data,

according to internal Monsanto communications.

Mr. Grant, who retired after Bayer acquired Monsanto for $63

billion, declined to comment, Bayer said.

Bayer said collaboration with outside scientists is important

for purposes such as testing safety and efficacy, and it provides

properly disclosed compensation for outside scientists' work,

adding that this pay isn't given to influence their scientific

opinions.

Helmut Greim, a retired toxicology professor at the Technical

University of Munich who has worked with Monsanto, said, "There is

this perception that industry is evil and that whoever is involved

with them is at least equally evil."

"If the industry asks a scientist to help," he added, "I see it

as my duty to do so. But one shouldn't let oneself be

influenced."

Some regulators say when a research paper discloses industry

funding, they take into account the possibility of corporate

influence on the findings. "We generally are a bit more

suspicious," said Bjorn Hansen, executive director of the European

Chemicals Agency.

The chemicals agency and the European Food Safety Authority both

re-examined glyphosate studies questioned by plaintiffs' attorneys

and let stand their approvals. The agencies said they look at the

raw data in research, so that the kind of study the attorneys

question -- a review of past research -- generally doesn't carry

much weight.

Health Canada also recently took a second look at studies on

which it had based its approval of glyphosate herbicides, after

critics raised concerns about Monsanto's role in research. The

Canadian agency assigned a separate group of its scientists to go

over the studies. Their review didn't change its conclusion.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is currently doing a

periodic review of the glyphosate science, ahead of a decision

expected soon on extending glyphosate's longstanding U.S. approval.

The EPA's most recent review of glyphosate's potential human risk,

in late 2017, continued to find the chemical unlikely to cause

cancer in humans.

A spokesman for the EPA said it has practices in place to

"ensure that [company]-developed data represent sound science."

Scientific research in industry and academia has become more

entwined over the years, scientists say, as corporations have

become a more important funding source. Since 2007, U.S. federal

government spending on basic scientific research has plateaued at

around $38 billion annually, according to data from the National

Science Foundation. Corporate funding has roughly doubled in that

time, to about $27 billion.

Companies or industry groups that finance research often include

in contracts a right to review early versions of studies, said

academics, who added that government-funded entities may attach a

similar requirement.

For researchers with fewer options allowing them to be fully

independent, "to some extent, they have to play by the industry's

rules," said Sharon Batt, an adjunct bioethics professor at

Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

A 1998 review of 70 articles on the safety of a hypertension

medication found that authors who produced conclusions supporting

its use were nearly twice as likely as neutral or critical authors

to have financial relationships with manufacturers. The review, on

drugs called calcium-channel antagonists, was published in the New

England Journal of Medicine.

A 2003 analysis of studies on industry-sponsored biomedical

research found corporate-funded studies were more than 3 1/2 times

as likely to show results favorable to companies as were studies

with no industry funding. The analysis appeared in the Journal of

the American Medical Association.

In 2002, researcher Susan Monheit was writing an article on

glyphosate herbicides used against aquatic weeds and sent a draft

to a Monsanto regulatory-affairs official for fact checking. The

official forwarded it to Monsanto toxicologist Donna Farmer,

according to emails that the Baum Hedlund law firm obtained in

discovery and that The Wall Street Journal reviewed.

Ms. Farmer told the official the paper needed organizational

work. "During one editing I had basically re-written the thing --

then decided that was not a good thing to do so I tried to just

correct the inaccuracies," she wrote to the regulatory-affairs

official, Martin Lemon.

In an interview, Ms. Monheit, who worked at the California

Department of Food and Agriculture, said Mr. Lemon passed along

Monsanto's suggestions by telephone and she followed some of them,

such as deleting references to old information. "I certainly didn't

want to use data that was out of date," she said, but "I was wary

of having Monsanto influence the article."

When her article was published in a weed-control newsletter

called Noxious Times, concluding the chemical posed minimal risk to

wildlife, a note described it as the product of a review of

previously published research and consultations with pesticide

chemists and eco-toxicologists. The note didn't name Monsanto.

Bayer didn't make the employees available for interviews.

In the late 2000s, Monsanto financed a study done partly by

Pamela Mink, then an assistant professor of epidemiology at Emory

University, reviewing past research on glyphosate's safety. Shown a

draft, Monsanto's Ms. Farmer suggested some edits, mostly to the

introduction, and circulated the draft to fellow company

scientists, according to documents produced in the litigation and

reviewed by the Journal.

One of the Monsanto scientists, Daniel Goldstein, added his own

suggestions. "There are a couple places where I read the sentences

several times, and I just can't gather what the underlying message

is," he emailed Ms. Farmer. The two suggested deleting redundant

phrases, asked for math to be double-checked and corrected

names.

When the paper was published in the journal Regulatory

Toxicology and Pharmacology in June 2012, some of the critiqued

passages didn't appear, while others were rephrased and expanded.

Brian Stekloff, a lawyer representing Bayer, said in court last

month that Ms. Farmer moved around words in the introduction and

added context about Roundup products that outside scientists would

not have had.

The final paper was significantly different from the draft but

had the same conclusion, which was that the researchers had found

no pattern showing glyphosate exposure caused cancer in humans.

Its authors were listed as Dr. Mink and three other researchers

who, like her, were affiliated with science consultancy Exponent

Inc. The paper said one of the authors had been a paid consultant

to Monsanto. "Final decisions regarding the content of the

manuscript were made solely by the four authors," it said.

Dr. Mink didn't respond to requests for comment.

Dr. Greim, the retired Munich toxicology professor, said

Monsanto approached him in 2013 about helping it publish some

unpublished internal research it earlier submitted to regulatory

bodies.

He said Monsanto officials sent him a draft of a report. "I told

them, 'That's not how it's done, you need a lot more information'"

to support the conclusions, Dr. Greim said. He said he went back

and forth with company scientists for months, asking them to add

details such as the number of animals and organs studied, and

changing the presentation of the results, until he felt the paper

was satisfactory.

Monsanto accepted all of his suggestions, Dr. Greim said, and

"there were a lot of passages I ended up writing." He said he was

paid EUR3,000, or about $3,400, for his work.

When the paper was published in Critical Reviews in Toxicology

in 2015 -- finding no link between the Roundup ingredient and

cancer -- Dr. Greim appeared as lead author. A "declaration of

interest" section said that he had been paid by Monsanto and that

his three co-authors had connections to the glyphosate business,

including one who was employed by Monsanto.

In an internal Monsanto memo released by the Baum Hedlund law

firm, a Monsanto scientist listed among his accomplishments "ghost

wrote cancer review paper Greim et al. (2015)."

Dr. Greim, who has sat on various German and EU scientific

advisory committees, said he didn't care what was said internally

because that wasn't what happened.

Bayer attorney Mr. Stekloff, speaking generally, said in court

last month that there were instances of "dumb emails" and "bad

language" among the many company documents produced in the case,

but "the overall record demonstrates that this was a company

committed to testing and committed to science."

--Sara Randazzo and Sarah Nassauer contributed to this

article.

Write to Jacob Bunge at jacob.bunge@wsj.com and Ruth Bender at

Ruth.Bender@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 08, 2019 11:19 ET (15:19 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

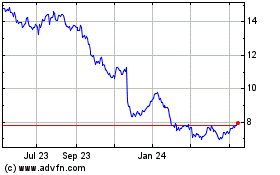

Bayer Aktiengesellschaft (PK) (USOTC:BAYRY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

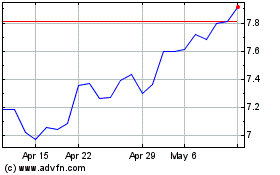

Bayer Aktiengesellschaft (PK) (USOTC:BAYRY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024