In its battle against Amazon, Walmart is betting on a future

where its supercenters will quickly get groceries to your door,

replace the doctor's office and rent out computing power to passing

drones and autonomous cars.

By Sarah Nassauer

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (December 21, 2019).

After years of internal debate about how to compete with

Amazon.com Inc., Walmart Inc. boss Doug McMillon took the stage at

a recent strategy meeting and revealed the centerpiece of his plan

to thrive in an e-commerce era: giant stores.

Walmart, he told executives at the meeting, wasn't going to win

by building an unprofitable e-commerce operation or other

stand-alone ventures. Instead, its supercenters could be the heart

of a web of businesses all working together to attract shoppers and

drive profits.

The supercenters are sprawling stores of around 180,000 square

feet offering 100,000 products, bathed under LED lights. Groceries,

clothes, camping gear and televisions are for sale; customers can

also fill medical prescriptions, transfer money or get their hair

done. They're often open 24 hours and are community gathering

spots, becoming backdrops for videos of teenage pranks that pop up

on YouTube, or a place for senior citizens to take a walk in cold

weather.

The re-emphasis on the giant outlets Walmart started building in

the 1980s was a change from a strategy laid out just a year ago.

Then, at an investor meeting, Mr. McMillon described stores,

e-commerce and other businesses as individual ventures serving the

Walmart customer in different ways.

In the new view, disparate parts of the business would interact

to drive profitable growth. Walmart would capitalize on its

customer data to sell online advertising to brands, according to a

person familiar with the presentation.

Turning far outside its retail expertise, Walmart plans to build

"edge computing" capacity, in which data is processed physically

close to where it is being collected, a faster system than sending

data to the cloud. That system, spread out among retail locations,

could be rented out amid new demand by autonomous vehicles and

other systems that may use the technology to process large amounts

of data quickly, according to people familiar with the company's

plans.

Added warehouse and shipping capacity could be sold to

third-party sellers, to allow more companies to easily sell their

wares on Walmart.com. Customers would have a bigger product

selection, and Walmart could collect fees for processing and

shipping. And online orders for Walmart's groceries and other items

could increasingly be fulfilled by traditional stores, where

customers pick up goods.

"The time where people might have been worried that our boxes

were too big has long passed," Mr. McMillon said at an investor

meeting earlier this month. "The supercenter footprint and

positioning gives us a great opportunity to expand services and

help the economics of the model." Walmart declined to make Mr.

McMillon available for an interview.

Adding to market share

The retailer has largely weathered the shift to online shopping

and the rise of Amazon. Sales from U.S. stores and websites open a

year have risen for 20 straight quarters, as Walmart added online

grocery pickup in store parking lots, cleaned up stores and lowered

prices. As other traditional retailers lose customers and fail to

compete, Walmart has increased its market share.

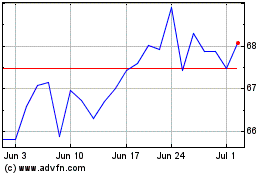

The company's stock has surged nearly 30% so far this year,

trading near the highest levels since the retailer went public in

1970.

But the sales gains have been costly. Walmart spent heavily to

improve stores and to grow online, and the efforts have been

dependent on U.S. stores producing steady profits to fund

investments. Walmart executives have been wrestling with the best

way to continue, according to people familiar with the

situation.

Walmart's revenue is more than twice Amazon's, but the pace of

Amazon's profit growth is racing past Walmart's. Last year,

Amazon's operating income tripled to $12.42 billion, while

Walmart's operating income grew 8% to $22 billion. Amazon's profits

largely come from its cloud-computing arm and nonretail activities,

such as advertising.

Amazon Web Services, the cloud-computing business, generated $25

billion of revenue in the first nine months of the year, or 13% of

the company's total, yet it generated 62% of Amazon's operating

income in the period. Ad revenue at Amazon hit over $3.6 billion in

the most recent quarter. The company is now the third-largest U.S.

seller of digital ads after Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.'s

Google, according to eMarketer.

At Walmart, more leaders are asking, "Where is our cloud?" said

one former Walmart executive. "We can't do this without another

revenue source."

Beginning in 2016, Walmart moved aggressively onto Amazon's

e-commerce turf. It purchased Jet.com, an unprofitable startup

created to underprice Amazon on millions of items. Jet's founder

Marc Lore and much of his staff took over Walmart's wider

e-commerce operations. The company soon took "Stores" out of its

corporate name as "a symbol of how customers are shopping us today

and how they'll increasingly shop us in the future," Mr. McMillon

said at the time.

Mr. Lore and his team poured investment into e-commerce

operations by lowering prices online, spending more on marketing

and prioritizing faster shipping. Mr. Lore pushed Walmart to better

integrate its store and online activities for shoppers, according

to people familiar with the situation. The team also scooped up

smaller e-commerce sites, including women's apparel company

ModCloth, outdoor retailer Moosejaw and men's apparel brand

Bonobos.

Online sales grew, but losses mounted amid the high costs. Last

fiscal year, U.S. online operations lost around $2 billion -- more

money than planned for the second year in a row, according to

people familiar with the figures. Though the e-commerce unit has

long lost money, failing to hit targets was problematic for a

company obsessed with frugality that finely calibrates its

financial goals, said some of these people.

A Walmart spokesman declined to comment on e-commerce

losses.

The website, selection and shipping speeds still need to

improve, Mr. McMillon said at the investor meeting earlier this

month. "I would have thought we would have been further along in

e-commerce," he said. "We're not pleased. We'd like to go

faster."

By the end of last year, executives in the e-commerce unit heard

from Mr. McMillon, Mr. Lore and other leaders that it was time to

aggressively cut spending, according to people familiar with the

situation.

"It was a whipsaw effect from one year to another," said a

former executive on the e-commerce side of the business. "In the

beginning it was all about growth, how can you win share away from

Amazon," the person said. "Now it's about profit."

Earlier this year Hayneedle, the online furniture seller that

Jet.com acquired, cut a third of its staff. Bonobos laid off

workers. What remained of Jet's headquarters staff was folded into

the rest of Walmart. Modcloth was sold. Walmart has told Bonobos

and Moosejaw they need to stop losing money, according to people

familiar with the situation. Walmart is also exploring a sale of

Vudu, the video streaming service it bought in 2010, according to a

separate person familiar with the situation. The unit faces

challenges as competitors from Netflix Inc. to Walt Disney Co.

invest heavily to produce their own content.

Borrowing from Disney

Walmart saw that a bright spot in e-commerce was directly tied

to its stores: more than half of the 40% growth in U.S. e-commerce

sales last year came from expanding online grocery pickup or

delivery service run out of stores, according to people familiar

with the figures. At the same time, it was seeing results from its

push to improve stores, snagging shoppers from other traditional

chains.

At the recent strategy meeting, Mr. McMillon told top executives

that giant stores could be the base for new ventures like fast

delivery, health clinics and other services, according to the

person familiar with the meeting.

The concept borrowed from a famous 1957 sketch that laid out

Walt Disney's blueprint for growth at his film production company,

Mr. McMillon said during the meeting, according to the person. The

drawing detailed how cartoon movies could feed profits in other

businesses, such as television, comics, toys and theme parks; and

how those operations, in turn, could prop up the film studio. As

some movie studios struggled at the time, Disney continued to grow

by using the interconnected profit formula.

Walmart's stores could also act as a base for potentially

profit-making technology infrastructure or business-to-business

services.

In edge computing, computing power is physically close to where

data is being collected -- in contrast to cloud computing, in which

computing power is located in distant server farms, slowing down

processing.

More devices such as drones, autonomous cars and sensors collect

large amounts of data that could be processed by edge-computing

systems.

It takes around a quarter to half a second for data from a

device to reach the cloud. That length of time "doesn't sound like

a lot, but if you are in your car and it's trying to recognize a

ball rolling out in the street or a kid running behind the ball,"

that might be a decision that needs to be made faster, said Rob

High, chief technology officer for IBM Edge Computing, who isn't

working with Walmart on the project.

Hypothetically, autonomous car makers could contract with

Walmart to do on-the-fly, fast calculations in cars driving through

town, hopping on and off various stores' systems. Around 90% of

Americans live within 10 miles of a Walmart, the company says.

5G rollout

Mr. High said the rollout of faster, wireless 5G networks could

allow more edge devices in a given area to be connected at once,

making the technology more useful.

Walmart executives have met with large telecom companies to

discuss allowing the firms to install 5G antennas on the roofs of

stores for a fee or to provide access to faster network

connections, said a person familiar with the talks.

The retailer is already adding computing power to its stores to

process data from new technologies such as robots that clean

floors, sensors that alert staff when a freezer is too warm and

systems that use cameras to visually track the pace of sales.

Walmart executives think there will be excess capacity to sell,

according to people familiar with the plans.

Walmart may not go through with the plan to use edge computing

to generate profit, and some executives have expressed skepticism

internally about pursuing the effort, said a person familiar with

the situation.

The Walmart spokesman declined to comment.

In May, Walmart hired a former Google and Amazon executive as

global chief technology officer, a newly created position that

reports directly to Mr. McMillon. Suresh Kumar previously spent

about four years at Microsoft Corp. working on cloud

infrastructure.

Last year, former Walmart International CEO David Cheesewright

began researching artificial intelligence and technology that might

help Walmart boost profits or save money, according to people

familiar with the situation.

Mr. Cheesewright met with a range of AI and other experts and

led sessions for other executives to educate them on his findings.

By the end, he had compiled a list of 20 ideas, including edge

computing.

As another way to boost profits, Walmart is working to sell more

of its vast trove of data on hundreds of millions of shoppers who

buy online or use credit cards in stores, and to use that data to

sell more advertising.

In February, at a conference with suppliers, executives openly

discussed plans to create an advertising network that could help

brands like Kellogg's and Tide target online ads based on Walmart

shopper data. It was a service that Walmart had previously relied

on a unit of WPP PLC to sell.

The advertising effort has had a bumpy start, according to a

former executive in the Walmart Media Group. Technical snafus after

the business was brought in house caused many ads that had been

sold to not appear online, according to former executives familiar

with the situation and executives at consumer goods companies.

Walmart's advertising business is growing, said the Walmart

spokesman. "As you would expect when you're building a complete

in-house media business, we're learning and iterating along the

way."

Walmart.com is now working to grow faster, but more profitably.

The company plans to add e-commerce warehouse capacity to have more

of its products available for next day delivery, according to a

person familiar with the situation. Like Amazon, Walmart also plans

to invest in more capacity to offer fulfillment services and

warehousing for third-party merchants -- the outside companies that

list their goods on Walmart.com.

At Amazon, the majority of merchandise comes from outside

sellers, who pay Amazon fees to list or ship products. That has

fueled rapid growth while also causing problems, with some

customers and sellers saying Amazon's marketplace is peppered with

knockoffs or unsafe products.

Amazon said it prohibits the sale of counterfeit products and

requires all products sold to comply with applicable laws and

regulations, according to an Amazon spokeswoman. "Safety is a top

priority," she said.

On an earnings conference call last month, Mr. McMillon said

Walmart needed to improve profits at its e-commerce operations. The

company moved several Bentonville, Ark.-based Walmart veterans into

e-commerce leadership roles earlier this year, including Ashley

Buchanan as chief merchant and Steve Schmitt as finance chief.

Earlier this year, Mr. Lore raised eyebrows around the office by

alternately wearing two black baseball hats with white lettering

reading either "innovator" or "operator," according to people

familiar with the situation.

In a meeting, wearing the "operator" hat, Mr. Lore jokingly

explained the hats as a way to convey to everyone that he and the

team could operate the business effectively as well as push Walmart

to try new tactics, according to some of the people.

Mr. Lore wore the hats a couple of times to emphasize to his

team the need for dexterity on both fronts, said the Walmart

spokesman.

"He was like, I'm both," said one of the people familiar with

the situation. "And if you are confused look at my hat."

Write to Sarah Nassauer at sarah.nassauer@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 21, 2019 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

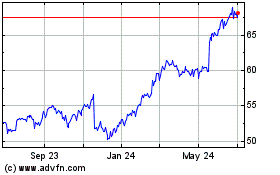

Walmart (NYSE:WMT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Walmart (NYSE:WMT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024