By Lauren Weber and Rachel Feintzeig

Darrell Ford's supervisor calls him almost every day, asking

when he'll return to his building-maintenance job in Duluth,

Minn.

"We don't have an answer because we don't have anyone to watch

our son," says his wife, Tasha Ford. Mr. Ford cares for their

4-year-old son, Elijah, while Ms. Ford works from home for

UnitedHealth Group Inc., helping mental-health providers file

claims.

Because Elijah has previously had respiratory problems, the

Fords pulled him out of his day-care center in March when the scope

of the coronavirus pandemic was becoming clear. The Fords would

place Elijah in home-based day care, but none in their rural

Minnesota town have space for him, and searches on Facebook for a

babysitter have been unsuccessful.

Some legislators and commentators worry that generous

unemployment checks will discourage people from going back to work,

but many U.S. workers are coping with a more quotidian barrier: a

lack of child care. As the novel coronavirus blazes through the

country, most schooling has moved online and thousands of day-care

facilities have shut down, either by decree or because demand has

cratered.

Now, as some governors loosen restrictions and companies call

employees back to work, parents are scrambling to find care. As of

early April, nearly half of child-care facilities nationwide had

closed completely, and 17% remained open only for the children of

essential workers, according to a survey of 5,000 child-care

providers conducted by the National Association for the Education

of Young Children. Schools in 40 states have been ordered to stay

shut through the end of the school year.

Today a coalition of business and early-childhood-education

groups is asking Congress for targeted stimulus designed to ensure

that day-care centers remain viable. Even before the pandemic,

day-care centers operated on thin margins, says Sarah Rittling,

executive director of the First Five Years Fund, which advocates

for stronger early-childhood education and is a member of the

coalition. "Now, without money coming in, the industry is really on

the brink," she says.

Many day-care facilities cannot survive if enrollment falls

below 85%, says Michael Madowitz, an economist at the Center for

American Progress who studies the child-care industry.

Given that the approximately nine million day-care slots

normally available in the U.S. are already too few to meet demand,

the coalition groups say, any loss of capacity will put extra

pressure on parents who must have child care to stay in the

workforce. "Child care is underpinning all of that," says Ms.

Rittling.

Millions affected

At Young at Heart Learning Center, a day-care and before- and

after-school program in Charlotte, N.C., enrollment has dropped

from 43 children before the pandemic to 14, according to owner

Vickie Collins.

Some parents have opted to stop sending their children to the

center, either because of fears they would get sick or because the

parents are working less and don't need as much help. Others were

forced to pull their children out in early April after Ms. Collins

received a letter from the state specifying she could only care for

children of essential workers.

Ms. Collins worries that the drop in enrollment could lead to

less funds from the state; most of her clients are low-wage workers

who qualify for free day care from North Carolina, money that gets

deposited directly to Ms. Collins based on attendance.

Millions of workers with young children can't work without

someone else supervising their children, in arrangements ranging

from schools and day-care facilities to babysitters and

grandparents. In 2019, more than 50 million U.S. workers had

children under the age of 18; almost half that number had children

under age 6, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

For single parents, the options are especially slim. Ingrid

Johnson, a sheet-metal apprentice at a Huntington Ingalls

Industries Inc. shipyard in Pascagoula, Miss., leaves for work at

around 5 a.m., and used to drop off her two sons, ages 7 and 8, at

the one day-care center that opened early enough to watch them

before a van brought them to school. Now, with schools and day care

closed, the boys stay home and are supervised for a few hours a day

by Ms. Johnson's 12-year-old niece.

"She's not the age I would like her to be, but it's the best

option I have left," says Ms. Johnson, a single mother who found

her job last year after completing a training program offered by

Moore Community House in nearby Biloxi. She also bought her boys

tablets, "so I can call and chat with them during the day to make

sure they're OK."

Ms. Johnson has been able to scale back to two full days and two

half days of work most weeks. That reduces her paycheck, but it

gives her some time to catch the boys up on their schoolwork.

An overwhelming job

Childcare as an economic and workforce issue is gaining

attention with business organizations, says Ms. Rittling. For

example, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation is a member of the

coalition seeking to raise the issue's visibility. But individual

companies have been slow to help employees with what is typically

considered a private problem for families to solve alone.

Some employers are offering extra support in light of the

pandemic. Mindy Nelson works in client services for

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP in Atlanta. The firm will reimburse up

to $2,200 of emergency child-care expenses, but Ms. Nelson, a

single mother to a 5-year-old, hasn't yet tapped it. "I don't have

anywhere to spend it," she says.

So far, she is working from home and managing her daughter's

online classes, but school ends in a few days and she expects most

summer day camps won't operate. She hopes to hire a babysitter to

fill the gaps.

Rachel Otis, who works for a church in Jacksonville, Fla.,

returned from maternity leave to her digital-communications job the

first week in March. She soon found herself struggling to juggle

the job with parenting her 4-month-old and 2 1/2 -year-old.

The home day-care facility where she and her husband, a nurse in

the intensive-care unit at a local hospital, send their toddler

daughter closed for the second half of March as the novel

coronavirus gained speed in the U.S. Then, last month, Ms. Otis's

husband began treating Covid-19 patients at the hospital. The

couple decided to keep their daughter home for a few weeks to

reduce the potential for exposure of her day-care provider and the

other children there to the virus. At the end of April, with her

father off the Covid-19 assignment, the toddler started going back

to day care part time, but the couple is limiting her attendance to

days when work obligations or other circumstances leave them little

choice.

Working, parenting, managing the household and supporting a

spouse on the front lines has been overwhelming, Ms. Otis says. If

her husband gets assigned to the Covid-19 patient area again,

they'll pull their daughter out of day care for another stretch.

But Ms. Otis says child care is crucial to her career. "It's the

only way I'm able to continue to work," she says.

Ms. Weber and Ms. Feintzeig are Wall Street Journal reporters in

New York. They can be reached at lauren.weber@wsj.com and

rachel.feintzeig@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 07, 2020 06:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

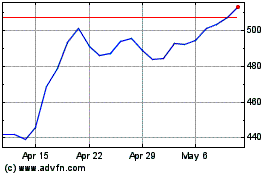

UnitedHealth (NYSE:UNH)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

UnitedHealth (NYSE:UNH)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024