By Tim Puko

DELAWARE CITY, Del. -- The oil refinery owned by PBF Energy Inc.

near this Delaware Bay town was mothballed nearly a decade ago.

Today it is running almost full-bore, and PBF and a business

partner are spending $100 million to expand it.

The refinery is seeking to capitalize on new international rules

that require cleaner-burning fuels on the world's oceangoing ships

starting Jan. 1.

U.S. refiners are anticipating a bonanza. The industry estimates

it has spent $100 billion on upgrades in the last decade to make

cleaner fuels, putting it in a position to boost revenues if the

rules raise the demand and prices for the products it makes, as

many expect.

The new rules were met with skepticism by the Trump

administration and others concerned about the impact on jobs and

energy prices. At places like Delaware City, however, the upgrades

required to meet the new standards have translated into more

good-paying jobs, said James Maravelias, president of the Delaware

Building Construction Trades Council.

As car makers and chemical plants have left the region, he said,

refiners have become some of his members' most reliable

employers.

"Energy is pretty much it for us," said Mr. Maravelias, who is

based out of Newark, Del. "There's no other industry that's

bringing in those kinds of jobs to Delaware right now."

At refineries, maintenance work -- usually conducted when the

refinery is shut down -- often employs 1,200 people at a time, Mr.

Maravelias said. And expanding the plant in Delaware City suggests

a future full of even more of those tuneups and more work to go

around, he added.

A rosy outcome isn't certain for everyone affected -- other

sectors, countries and even refiners -- but some analysts and

economists are expecting that a boost for refiners will have a

wide-ranging positive impact. With record U.S. fuel output leading

to more exports and fewer imports, more revenue stays within the

country, often reinvested.

Strong investment usually produces more economic growth than

does strong consumption, said Kevin Book, managing director of the

analysis firm ClearView Energy Partners LLC. So he expects that

U.S. refiners would profit and that rising investment would produce

a net benefit for the economy even if consumer prices rise.

"More money for U.S. refiners is generally good news," Mr. Book

said. "It's awfully hard to argue that in the aggregate this is bad

news."

The marine-fuel rules were imposed by the International Maritime

Organization, an arm of the United Nations, with the aim of

lowering sulfur pollution that can cause respiratory ailments and

aggravate heart disease.

A fast way for ships to come into compliance is to switch to

using more low-sulfur diesel or similar fuels known as distillates.

Many expect that to cause a surge of demand and price increases for

those fuels. While that could help the refiners that make them,

retail consumers could get hit in the pocketbook because that type

of fuel is still widely used as heating oil in parts of the

Northeast.

They could face price increases for diesel and distillates of 5%

to 20% due to the U.N. rules, analysts estimate. That has raised

concerns at the White House about rising energy prices in an

election year.

In October, the White House started a push to soften early

enforcement of the rules, slowing a rollout over several months.

Shares of independent refiners plummeted after The Wall Street

Journal reported the effort.

The full implications of the rules weren't well understood, and

dire initial economic forecasts caused fear, said Mandy Gunasekara,

who was a senior policy adviser at the Environmental Protection

Agency until earlier this year. As people learned more, those fears

receded and officials better understood how the U.S. might benefit,

she added.

"The U.S. is in very good standing because of forward-looking

investments by our refiners," said Mrs. Gunasekara, who now runs a

strategic-communications business.

White House advisers haven't ruled anything out, but they have

stopped actively trying to slow the rollout, according to lobbyists

and analysts familiar with the matter. U.S. officials didn't again

broach the proposal to delay the rules during IMO committee

meetings in London two weeks ago, according to analysts and

interest groups that attended or followed the meetings. That was

the last round of meetings before the sulfur cap takes effect.

"The United States is not seeking to change the existing IMO

2020 deadline that was certified in October 2016. We are continuing

to assess the macroeconomic impacts of implementation to consumers

and industry," a senior administration official said.

More-recent economic changes and forecasts have reduced the

urgency to intervene. Crude prices are down 23% from a four-year

high reached in October.

Crude prices are likely to go lower next year, despite changes

from the IMO, the Energy Information Administration has said in

recent months. It estimates pressure from the new rules could add

about $2.50 to every barrel of international benchmark crude in

2020, but other factors will offset that, causing average prices to

fall. Annual diesel and heating oil prices are likely to go up in

the U.S. by roughly 6% between 2019 and 2020, but won't be far

beyond recent peak prices from the fall of last year, the EIA

estimated this month.

It also predicted those changes will lead to broad gains for

refiners. The EIA estimated in March that pressure from the

marine-fuel rules would help entice U.S. refiners to run at record

capacity and near-record utilization in 2020. And the margins they

make for diesel fuel are likely to rise 35% from this year.

Singapore, the world's largest maritime refueling port, and

several major oil producers have said there would be ample supplies

at major ports.

There is still much uncertainty about the impact of the new

rules, analysts say. While it seems U.S. refiners will benefit,

they have to contend with international competitors who are

spending to catch up. That could cause a supply glut that wipes out

expected profits. While acute supply fears have eased, some concern

lingers. Some observers are worried that extreme shortages could

arise, leading to higher costs punishing consumers and slowing

other segments of the economy.

At Delaware City the rush is on, with 10-hour days and weekend

shifts.

PBF is working with Linde PLC to build a plant that makes

hydrogen, an additive PBF needs to make more of the cleaner-burning

fuels. Workers spent a recent weekend using 40 trucks of cement to

fill a hole 8 feet deep and as big as a football field.

Tiny, shimmering bolts stuck out from the pale gray foundation.

The bolts have to be set precisely and can't be off by more than

1/32nd of an inch. They are used to lock in a structure that

includes a tangle of pipes nine stories high. The project is

scheduled to be completed and operational by next spring, when new

demand is likely to start peaking.

"The U.S. refining sector is actually going to ensure the world

market is prepared," said Brendan Williams, PBF's in-house lobbyist

in Washington. "We hope there's a better understanding of not just

the preparedness, but the benefits...that could happen to the U.S.

economy."

Write to Tim Puko at Tim.Puko@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 26, 2019 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

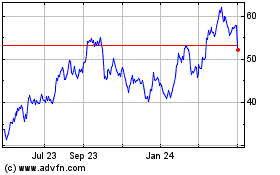

PBF Energy (NYSE:PBF)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

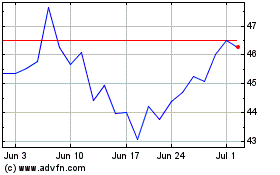

PBF Energy (NYSE:PBF)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024