Manipulating data in drug's race to market

By Denise Roland

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (September 14, 2019).

The startup had something incredible: a cure for babies with a

deadly neurological disease. Last year, the company was snapped up

by pharmaceutical giant Novartis AG, and by this past May, its drug

was the most expensive on the market.

In just a few years, the company, AveXis Inc., morphed from a

handful of hospital-based researchers into one of the

pharmaceutical industry's most stunning success stories.

But in the hurry to fulfill the drug's promise, AveXis

manipulated data that went into the drug's approval, Novartis and

the Food and Drug Administration now say.

And some former AveXis employees say there were other stumbling

blocks, separate from the manipulation cited by the FDA. They say

the company struggled to manage a fast ramp-up of its research and

manufacturing operations. They describe a race to develop the drug

that, at times, yielded mistakes, including misstated dosing

figures from early-stage trials of the drug.

AveXis went through a "fundamental shift in capabilities," a

Novartis spokesman said. He said it "evolved from an academic

setting to a commercial organization with leaders who had a deeper

understanding of the requirements of the pharmaceutical industry

and the FDA approval process." The spokesman said new leadership

established processes "in line with the needs for a company that

was gearing for product approval and commercialization."

In this field, there is plenty of incentive to move fast. Gene

therapy -- essentially treating a defective gene with a healthy one

-- is one of the hottest areas of pharmaceutical research, sucking

in billions of dollars of investment. Early pioneers, under

pressure from would-be patients and investors alike, are driven to

move quickly from promising research results to the manufacturing

of a safe, marketable version of their breakthroughs.

Along the way, these nimble startups can struggle to adapt to

the stringent requirements demanded by regulators and the large

pharmaceutical companies that typically snap them up. The FDA has

encouraged the acceleration, increasingly offering companies fast

track approval for promising, lifesaving drugs.

The stakes are high for Novartis, which paid $8.7 billion to buy

AveXis. The data manipulation -- which AveXis and Novartis have

acknowledged -- occurred before Novartis purchased the company.

Novartis later learned of the issue, but didn't alert the FDA while

the agency was reviewing the drug. The FDA has opened a criminal

probe into the matter, and Chief Executive Vas Narasimhan has

struggled to justify his decision to delay disclosure. Novartis has

said it wanted to conduct an internal probe before alerting the

FDA.

AveXis's drug, called Zolgensma, is one of the first

commercially available gene therapies -- and the world's most

expensive drug of any kind, at $2.1 million. Many doctors consider

it a revolutionary treatment for spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA, a

rare but particularly devastating genetic disease in babies. SMA

victims lack a gene crucial for muscle control and get

progressively weaker, struggling to move, eat or breathe.

Untreated, those with the most severe form, known as Type 1,

typically die by their second birthday. The FDA has said that the

data manipulation issue doesn't change its view that Zolgensma is

safe and effective and it has allowed the treatment to stay on the

market.

Zolgensma, delivered intravenously in a single dose, promises to

halt the disease. The drug's first clinical trial, conducted in

2014 and 2015, treated 15 babies. The first three received a lower

dose and the rest a higher dose. All 12 who received the higher

dose have passed their second birthday, with most hitting key

milestones like holding up their heads, eating by mouth and sitting

unaided. So far, there is no sign that the drug's effect decreases

over time.

Scientist Brian Kaspar and other researchers at Nationwide

Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, had been experimenting with

a possible gene-therapy treatment for SMA for years. In 2013,

AveXis licensed the technology, eventually bringing on Dr. Kaspar

as scientific founder.

The successful early trial generated excitement, just as

industrywide interest in gene therapies was rising. The company

listed on Nasdaq in 2016. A year later, a video showing the

progress of some of the babies in the clinical trial triggered a

standing ovation at a packed auditorium during a prestigious

neurology conference in Boston.

Working for the Chicago-based company, as it raced to win FDA

approval and ramp up commercial-scale production, was both

exhilarating and exhausting, according to former employees.

Long hours were the norm, they said. Chief Executive Sean Nolan

and Dr. Kaspar regularly reminded employees of the importance of

the new gene therapy. "We did [in three years] something that takes

most companies 10 years to do," said one former executive.

Some employees say they spotted sloppy practices relating to the

early clinical trial. Employees in 2016 found that the calculations

done by Dr. Kaspar two years earlier were imprecise, and flagged

this to executives, according to a former employee familiar with

the matter. Those calculations overstated the dose of the gene

therapy that had been given to babies in early-stage trials by a

factor of two, this person said.

A Novartis spokesman said AveXis employees discovered the

inaccuracy after a shift to a more precise method for calculating

the dosing. AveXis corrected those calculations almost four years

after they were first carried out, according to a Novartis filing

with the FDA last year.

AveXis staff also raised issues about the role of academic labs

in the drug's development, according to former employees. In its

first clinical trial, staff from Dr. Kaspar's laboratory had

conducted blood tests -- used to track the babies' immune responses

to the treatment -- at a lab at Nationwide Children's Hospital.

That lab wasn't certified to conduct patient testing, former

employees say. AveXis later contracted an outside, certified

laboratory to conduct tests for subsequent clinical trials,

according to these former employees.

A spokesman for Novartis said it wasn't uncommon for this type

of test to be performed in an academic laboratory setting "given

the emergence of the gene-therapy field at that time." Andrew

Wachler, a health-care lawyer, said any lab that performs patient

specific tests should be certified.

The scale-up of AveXis "was in many respects quite difficult"

for Dr. Kaspar, said a former AveXis executive, adding that Dr.

Kaspar sometimes expressed frustration that as the organization

grew it became more bureaucratic and decisions took longer.

To win eventual FDA approval, the fledgling company needed to

demonstrate it could ramp up commercial production of the

treatment. AveXis launched a new manufacturing facility in

Libertyville, Ill., near Chicago. The plant needed to run dozens of

successive batches of the gene therapy, and provide meticulous

documentation.

It was a round-the-clock operation, according to former

employees. It wasn't unusual for quality-assurance employees to be

hauled out of bed in the middle of the night if a potential issue

had arisen with a batch, according to former employees.

A Novartis spokesman said AveXis had a sense of urgency to get

the product to children in need. He said that many biotech

manufacturing plants work round-the-clock.

To win over the FDA, AveXis had to show the gene therapy made in

the company's new factory in Libertyville matched the treatment

made and tested at the hospital. To do so, scientists compared how

mice with SMA fared with the Libertyville product, versus how they

did on the original gene therapy from the hospital.

Those comparisons were done at an AveXis facility in San Diego.

They were later submitted as part of the drug's approval

application. The FDA signed off on them as satisfactory, according

to FDA filings.

But while the FDA was assessing the application, an AveXis

whistleblower reported to the AveXis leadership that there was a

problem with some of that data. The issue was escalated to

Novartis's Chief Executive Vas Narasimhan in early May, but the

company didn't alert the FDA until late June, about a month after

the drug had won FDA approval and gone on sale.

After Novartis reported the issue, the FDA descended on the San

Diego facility where the tests were conducted. Inspectors found a

host of problems, according to an FDA report of the inspection.

Staff didn't thoroughly review data discrepancies, for instance,

and didn't keep satisfactory records. FDA inspectors found a log

from August 2018 describing how the lifespans of mice used to test

the potency of the drug were recorded differently in different

places, according to their report. In the most extreme case, the

difference was 19 days. Inspectors went on to say, in the report,

that they saw no evidence staff, made aware of the error by

quality-control inspectors, made efforts to figure out what

happened. Novartis said it has responded to the FDA's concerns.

Novartis replaced Dr. Kaspar in the wake of the

data-manipulation issue. Dr. Kaspar has denied wrongdoing in

relation to the data manipulation, but didn't respond to requests

for comment for this article.

The manipulation "is the antithesis of the culture we built,"

said a former AveXis executive, who said the vast majority of

AveXis employees "were exceptional and did things with great

integrity."

Although the FDA has allowed the drug to stay on the market,

saying the data manipulation doesn't affect its efficacy or safety,

the episode has nonetheless sowed worry among parents of babies

with SMA. Cure SMA, a charity that raises money for research into

SMA, quickly arranged a webinar with representatives from AveXis

and the FDA to address concerns after the manipulation disclosures.

One participant asked whether Zolgensma was safe, and if the FDA

had been "duped" into approving it.

The FDA official on the call said the agency would have taken

the treatment off the shelf if it had any doubts. Dozens of babies

have been successfully treated with the drug. In some cases, babies

who once would have struggled to sit up unassisted are now

walking.

Eleven-month-old Isaac Olthoff was scheduled to receive

Zolgensma when the data manipulation came to light. His mother,

Michelle, said the announcement gave her pause, but she was soon

reassured by the FDA's decision to keep the treatment on the

market. Isaac received Zolgensma a week later.

--Joseph Walker contributed to this article.

Write to Denise Roland at Denise.Roland@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 14, 2019 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

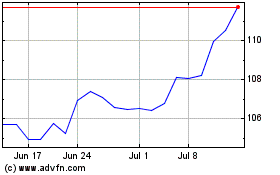

Novartis (NYSE:NVS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

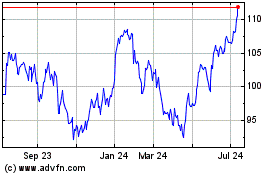

Novartis (NYSE:NVS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024