By Julia-Ambra Verlaine

Yields on U.S. government bonds fell to new lows and stocks

dropped Friday after a better-than-expected jobs report failed to

assuage growing investor fear over the global coronavirus

crisis.

The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note, a key

reference rate for borrowing costs throughout the economy, fell for

a 12th consecutive session to close at a new all-time low of

0.709%. The yield regained some ground as stocks pared losses in an

end-of-trading recovery.

That move upward wasn't enough to push the Dow Jones Industrial

Average into positive territory for the day. But the index did post

a slight gain for the week, a period marked by violent swings as

investors gauged the progression of the coronavirus and a surprise

rate cut of a half-percentage point by the Federal Reserve.

The Dow ended Friday down 1%, at 25864.78, paring what at one

point earlier in the day had been a drop of more than 800 points.

The blue-chip index has still fallen around 9% since the start of

the year. A sharp drop in the price of oil hit energy stocks, while

investors also punished bank shares.

Analysts and investors said a muted response to Friday's monthly

jobs report, which showed employers adding more positions in

February than expected, occurred because companies reported their

headcounts before cases of coronavirus began mounting in the U.S.

Many investors already expect the Fed to cut its short-term

benchmark rate again by its March 17-18 meeting at the latest.

While stocks garnered much of the investing attention during the

week's tumult, equally dramatic moves occurred in bond markets.

Treasury yields, which fall when bond prices rise, plunged in

overnight trading before the jobs report. Investors intensified the

rush to safer assets and anticipated lower short-term rates for the

foreseeable future as the economic fallout from the virus spreads

with each canceled flight and shuttered factory.

Adding fuel to the yield decline: the insatiable demand of major

U.S. banks, whose hedging needs have risen with each fresh decline

in rates.

Banks need to buy around $1.2 trillion of 10-year Treasury notes

to offset risks on mortgages and bank deposits, according to

JPMorgan research estimates. Commercial banks own around $3

trillion of U.S. Treasury and government-agency securities, Fed

data show.

The 10-year yield, which helps set borrowing costs on everything

from mortgages to business loans, has been pushed lower by worries

about the coronavirus's potential impact on the economy, which

resulted this past week in the Fed's first emergency rate cut since

the financial crisis.

The yield has declined precipitously from 1.90% at the beginning

of the year. The plunge both reflects and intensifies commercial

banks' efforts to manage balance-sheet risks including sensitivity

to interest-rate swings. This practice, known in industry parlance

as convexity hedging, has been a significant factor in the bond

market for years but has become even more momentous as a result of

tighter rules adopted after the 2008 crisis.

"Convexity tends to exacerbate market moves -- if rates are

going lower, convexity will make the move sharper," said Gennadiy

Goldberg, U.S. rates strategist at TD Securities.

Here is how it works. When interest rates fall, many homeowners

who took out fixed-rate mortgages refinance to lock in lower

monthly payments. The owners of the relevant mortgages and

mortgage-backed securities -- including the banks -- lose out on

higher payment streams. As a result, the prices of mortgage bonds

tend to rise less in any given bond rally than Treasury securities

or some other bonds, making them "negatively convex."

Banks hedge their holdings of mortgages and other assets to

limit these sorts of losses, but doing so often entails buying new

assets including Treasurys. Banks also use interest-rate

derivatives to offset potential losses from changes in rates --

usually swaps, in which the bank typically exchanges the right to a

fixed payment for a floating payment under specified terms.

The sharp decline in rates is making banks even bigger buyers of

Treasurys, as the probability of mortgage refinancing increases and

they seek to bridge expected income shortfalls generated when

higher-paying fixed-income securities "prepay," as traders say when

refinancings enable a bond to be paid off early. The same dynamic

plays out to some extent with deposits, which are liabilities that

the banks seek to match with assets, a match that often comes under

pressure when the rate environment changes significantly.

The three largest U.S. banks by assets, JPMorgan Chase &

Co., Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co., have steadily

grown since the financial crisis, expanding their mortgage books

and raking in more consumer deposits through money-market, checking

and savings accounts. That means bigger hedges to manage risks.

JPMorgan held an average of $215 billion of residential

mortgages on the books at the end of 2019, compared with $143

billion a decade earlier. Wells Fargo deposits climbed to $890

billion last year from $787 billion in 2016. Interest-bearing

deposits at Bank of America jumped nearly 20% over two years to

$900 billion in 2019.

Partly as a result of larger mortgage and deposit balances, both

of which can require hedging, banks have grown more sensitive to

rate changes. JPMorgan research analysts estimate the expected

increase in net interest income for banks for a 1-percentage-point

increase in rates is $8 billion, up from $6 billion last year.

Those figures generally work in reverse when rates fall.

This sensitivity can be painful when banks misjudge the economic

outlook or market sentiment. In 2018, many large banks were

wrong-footed by the year-end market meltdown that ended in the

Fed's decision to begin cutting rates following several years of

increases.

The scale of these moves and the ripples from banks' efforts to

hedge them underscore the tightrope the Fed is trying to walk as it

seeks to keep the economy on track in the face of rising

coronavirus fears.

"If the Fed overreacts and cuts too much, it creates other

dynamics that hurt insurance companies, pension funds and the

banking system," said Rick Rieder, chief investment officer of

global fixed income at BlackRock.

Compounding the problem, banks are hamstrung by postcrisis

capital rules that have made assets including corporate bonds

expensive to hold, making it difficult for them to buy assets with

long duration that they can carry on the balance sheet.

Accordingly, they are now buying products long preferred by

insurance companies, including collateralized mortgage obligations

-- financially engineered mortgage bonds sold in grades that can

make higher-rated ones less vulnerable to prepayment risk -- in the

hunt for longer-lived assets that they can hold.

"This rally has exacerbated an already significant issue," said

JPMorgan's head of U.S. interest-rate-derivatives research, Josh

Younger.

Write to Julia-Ambra Verlaine at Julia.Verlaine@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 06, 2020 18:30 ET (23:30 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

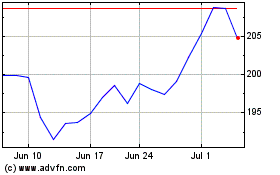

JP Morgan Chase (NYSE:JPM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

JP Morgan Chase (NYSE:JPM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024