By Nora Naughton, Matt Wirz and Cara Lombardo

Years before it was forced into bankruptcy, Hertz Global

Holdings Inc. decided to replace a fleet that was becoming a

turnoff to customers.

Because Hertz was strapped, it bought what was cheap and

available, doubling down on sedans instead of the SUVs customers

wanted. "The fleet had aged to the point that we had customer

mutiny," said former Hertz Chief Executive John Tague. "We were

solving the biggest problem, but not solving all the problems."

That decision was emblematic of a series of strategic missteps

and other blunders that kept Hertz behind competitors and buried

under debt. The downturn caused by the coronavirus was just the

icing on the cake. Hertz on Friday filed for bankruptcy

protection.

The pandemic's economic fallout has triggered a wave of

bankruptcies, including chapter 11 filings in recent weeks by

energy companies and retailers such as J.C. Penney Co. and Neiman

Marcus Group Inc. It has pushed more-stable companies to preserve

cash and go deeper into debt to shore up liquidity.

In many cases, the companies in the most trouble today are those

who were also in the most trouble yesterday. The pandemic means

muddling through is no longer an option.

The crisis has battered the whole rental-car industry with a

plunge in bookings. Hertz was more vulnerable than competitors,

having borrowed about $19 billion directly and through a series of

complex financial transactions. In addition to its sedan

commitment, the company was held back by its troubled 2012

acquisition of Dollar Thrifty and efforts to move into the

leisure-traveler market, a niche dominated by Avis Budget Group

Inc. and Enterprise Holdings Inc.

Hertz's collapse is among the highest-profile corporate defaults

from the pandemic's impact on air and ground travel. "All the money

spent on overpriced mergers and acquisition, the questionable fleet

management," said Glenn Reynolds, co-founder of research firm

CreditSights, who has covered Hertz for more than two decades, "it

caught up with them."

Hertz was already struggling to fend off threats to its business

from Uber Technologies Inc., Lyft Inc. and other ride-hailing

firms. And its better-capitalized rivals, Avis and Enterprise,

moved faster to update technology, refresh their fleets and

rebalance offerings with SUVs, analysts and former Hertz executives

said.

At its 2014 peak, Hertz's market value was above $14 billion,

about twice Avis's. It hovered around $2 billion for the past few

years until the threat of bankruptcy sent it below $500 million,

while Avis's market value stands around $1 billion.

"With the severity of the COVID-19 impact on our business, and

the uncertainty of when travel and the economy will rebound," Hertz

CEO Paul Stone said in a written statement late Friday of the

bankruptcy filing, "we need to take further steps to weather a

potentially prolonged recovery."

Hertz has cycled through four CEOs in less than a decade. The

latest change came this month when Kathryn Marinello, its CEO for

three years, clashed with her board over corporate strategy,

according to people familiar with the matter. and was replaced by

Mr. Stone, who recently ran Hertz's retail operations for North

America.

The 102-year-old company began as a fleet of 12 Ford Model-Ts in

Chicago and helped pioneer the rental-car business. It was

originally known as Rent-a-Car Inc. By the 1970s, Hertz was a

household name. With its airport counters and yellow logo, it was

the go-to for a reliable base of business travelers.

It went through owners including RCA Corp. and Ford Motor Co.,

which sold it in 2005 to a group of private-equity firms led by

Clayton Dubilier & Rice for $5.6 billion. The transaction

saddled the company with more debt. A year later, the sold out

their investment via an initial public offering.

By 2010, with the economy rebounding from the financial crisis,

then-CEO Mark Frissora, who led the company through the downturn,

decided to expand into the market for leisure travelers. After a

two-year pursuit and a bidding war with Avis, it acquired Dollar

Thrifty Automotive Group, which specialized in tourism and rentals

covered by auto insurers, for more than $2 billion.

To pay for the deal, Hertz borrowed heavily in bond markets,

increasing its corporate debt by about 50% to $6 billion, financial

filings show. Integrating the companies was fraught, not only

failing to deliver promised savings but also costing it money,

analysts, investors and former executives said.

'Lot of confusion'

"There seemed to be a lot of confusion on everything from

pricing to fleets to locations," said Michael McDowell, a former

longtime Hertz manager who worked in e-commerce for the company

until early 2019. "It was a big distraction trying to figure out

how to put it all together, much more than anyone imagined."

Mr. Frissora stands by the move to acquire Dollar Thrifty, his

spokesman said.

Toward the end of Mr. Frissora's tenure, Hertz made another

major change: It decided to hold on to the company's rental

vehicles longer, hoping to extend their life cycle by putting them

in discount-brand fleets as they aged. This move also delayed the

vehicle depreciation and gave a temporary bump to Hertz's financial

results, analysts said.

The change backfired. Customers complained about the condition

of the fleet's older vehicles, and many defected to Avis, analysts

and investors said.

After the debt-fueled Dollar Thrifty acquisition, Hertz had

little capacity to borrow, so it turned to one of the more arcane

corners of Wall Street, the market for asset-backed

securitizations, or ABS, which was reviving from a long hibernation

after the 2008 credit crisis.

Investment banks created financial trusts for Hertz to issue

bonds that bought vehicles, which were leased back to the company.

The bonds had much lower interest rates than Hertz could borrow at

because they were backed by the cars and had high credit

ratings.

Activist investor Carl Icahn disclosed a large position in

Hertz's stock in August 2014. Its share price, though around what

would be its peak, had been dented by accounting irregularities.

Mr. Icahn pressed for a change in management, citing the accounting

and operational problems.

Mr. Frissora stepped down in September 2014. In 2015, Hertz

restated three years of earnings, which it later said cost it $200

million. The Securities and Exchange Commission fined Hertz, which

didn't admit wrongdoing, and the company later sued Mr. Frissora

and other executives to claw back millions of dollars in

compensation from them tied to the accounting. The case is

pending.

Mr. Frissora, now a private-equity adviser, through his

spokesman denied wrongdoing. The spokesman said Mr. Frissora

presided over operational improvements and blamed Hertz's decline

on the executive churn following Mr. Fissora's departure.

As part of a settlement agreement to avoid a proxy fight, Hertz

gave board seats to three of Mr. Icahn's representatives, who

helped recruit Mr. Tague as CEO. When Mr. Tague stepped in at the

end of 2014, Hertz's rental-car fleet had aged significantly and

the company had lost at least three quarters of its staff in moving

its headquarters from New Jersey to Florida, according to analysts'

estimates.

Mr. Frissora's spokesman said the move was part of the

then-CEO's plan for integrating Hertz with Dollar Thrifty, and that

it made economic sense at the time.

Mr. Tague, now a private-equity adviser, said he felt the move

was a distraction, as he had trouble recruiting a new staff and

lost institutional knowledge. A former United Airlines Inc.

executive, Mr. Tague said he spent much of his tenure fixing

operational problems including the company's fleet while hoping to

lift results by applying an airline-like approach to pricing, where

customers paid a lower price for the rental car but extra for

add-ons.

Mr. Tague's efforts didn't impress investors, and he disagreed

with Mr. Icahn on how to prioritize the threat of ride-hailing

firms like Uber and Lyft, he acknowledged.

"I believed that our greatest threats were internal," Mr. Tague

said. "We had to address those before we got to the external

threats."

Aggressive borrowing

Hertz continued aggressively borrowing in the asset-backed

securities market, issuing riskier bonds to raise more money per

car starting in 2015. Its traditional rating firm, Moody's

Investors Service, didn't rate the new "Class D" bonds highly

enough, and Hertz turned to a competing firm, Fitch Ratings, to

rate the debt instead, a former banker who worked on Hertz ABS

deals said.

By the time Ms. Marinello took over in 2017, the company had

$13.5 billion of debt and was falling further behind on technology.

As more customers were opting for SUVs, Hertz had too many

fast-depreciating sedans it needed to sell. She executed a

turnaround plan aiming to take Hertz "back to basics" and pushed to

work with ride-hailing companies.

Hertz under Ms. Marinello continued to lean on asset-backed debt

to fuel growth, increasing ABS borrowing by about 40% to $14.4

billion over the past two years, according to financial

filings.

By early 2020, after four straight years of net losses, Hertz

saw revenue increase 6% in the first two months of the year.

But as the virus outbreak grounded thousands of flights and

travel lockdowns became widespread in mid-March, the company found

itself in survival mode and laid off 10,000 employees in North

America.

Hertz's undoing, in the end, wasn't only the pandemic but also

its dependence on financial engineering: In April, it faced a

roughly $500 million payment to ABS bondholders, a figure that

ballooned as used-car values dropped. It had about $1 billion in

cash on its books, and its board faced a choice: Preserve cash or

pay.

Ms. Marinello favored making a significant partial payment,

which she believed would appease creditors and avoid bankruptcy,

said people familiar with the matter. The board argued it was

better to negotiate with creditors and stockpile cash for a

prolonged dry spell, these people said. Ms. Marinello was

outnumbered, some of the people said.

On Thursday afternoon, there was still hope a deal might be

struck to give the company more time, these people said. By midday

Friday, the prospect faded when the top lenders wouldn't budge:

Hertz's operations were losing more than $200 million a month,

before having to make lease payments of roughly twice that, the

people said.

Around 10 p.m. Friday, Hertz filed for bankruptcy without a

clear plan with creditors in place -- a rare move for a company of

its size.

Since equity holders rarely survive a bankruptcy, Mr. Icahn, who

owns nearly 40% of Hertz, is expected to lose his entire roughly

$1.5 billion investment. That includes more than $200 million of

new shares bought last summer to help it pay down debt. People

familiar with the matter said he might not be entirely done with

the investment. He could invest further as the company emerges from

bankruptcy.

--Alexander Gladstone contributed to this article.

Write to Matt Wirz at matthieu.wirz@wsj.com and Cara Lombardo at

cara.lombardo@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 25, 2020 15:38 ET (19:38 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

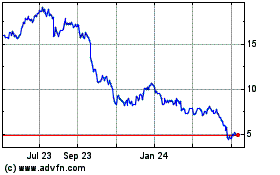

Hertz Global (NASDAQ:HTZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

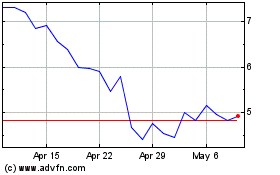

Hertz Global (NASDAQ:HTZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024