Goldman Opens Up In-House Moneymaker to Outside Investors -- Update

March 12 2019 - 4:13PM

Dow Jones News

By Liz Hoffman

A Goldman Sachs Group Inc. profit machine that has invested the

bank's own money in Asian property, African startups and troubled

U.S. retailers, among other ventures, is opening up to outside

investors.

Goldman plans to raise outside money for its special-situations

group, according to people familiar with the matter. Also under

discussion is a broader reorganization of the firm's various

private investing activities into a new unit that would seek to

raise new funds across a variety of strategies, the people

said.

The special-situations group has been run since 2013 by Julian

Salisbury, a detail-oriented Brit who joined the firm's management

committee two years ago. It has grown from about $20 billion on the

eve of the crisis to about $30 billion today, people familiar with

the matter said.

In the early 2000s it pioneered the sort of go-anywhere

investing that has caught on at private-equity firms such as TPG

and Blackstone Group LP, and it remains one of the most profitable

businesses at Goldman.

It will likely be combined with Goldman's merchant-banking

group, the historical home of the bank's private-equity

investing.

"Based on our track record, there is an opportunity to raise

additional third-party funds across equity, credit and real

estate," Goldman Chief Executive David Solomon told analysts

earlier this year. "We have a world-class alternative investing

franchise, which has generated strong returns over three decades

[and] presents us with extraordinary opportunities to partner with

clients to invest their capital alongside our own."

In a memo to employees last week entitled "Our Forward

Strategy," Mr. Solomon said growing the bank's alternative

asset-management business is a priority.

The discussions show how much has changed on Wall Street since

the financial crisis. In Goldman's last big push into private

equity, in the 2000s, it put billions of dollars of its own money

into megabuyouts. Now it seeks raise money from outside investors

like pension funds and clip steady fees for managing it.

Shareholders today value steady, low-risk businesses like money

management, setting off an asset-gathering race across Wall

Street.

The reorganization also shows Mr. Solomon busting up silos in an

effort to modernize and streamline the firm. Under a "One Goldman"

banner, he has launched a firmwide effort to better cover top

clients.

Scattered across Goldman are at least a half-dozen units tasked

with making investments, built over decades of ad hoc planning and

guarded jealously by their owners. Their results are comingled in

an "investing and lending" reporting segment that shareholders tend

to dismiss as opaque and unpredictable.

Merging them will create a unit resembling a smaller version of

KKR & Co. or Blackstone that executives hope will be better

understood and more richly valued by shareholders. The move may

eventually change how Goldman publicly reports its earnings, some

of the people said.

The firm weighed such a combination once before, in 2008 as the

crisis deepened, but the endeavor fell apart due to personality

clashes, a person familiar with the matter said.

Most banks spun off their private-equity arms after the 2010

passage of the Dodd-Frank financial law, which banned banks from

investing their own money into buyout funds and slapped heavy

capital charges on illiquid portfolios. Goldman held on more

tightly, betting that it could navigate the new rules.

It started doing deals straight off its balance sheet,

sidestepping the ban on funds. Successful investments of that

vintage included credit bureau TransUnion and financial-data firm

Ipreo. In 2017 Goldman raised its first buyout fund since the

crisis, a $7 billion pool that includes only a small amount of the

bank's own money.

The special-situations group has wide leeway to invest wherever

it sees an opportunity. In the late 1990s, it made a killing in the

wake of the Asian financial crisis. These days it is more of a

middle-market lender, serving midsize companies that have trouble

borrowing elsewhere. It has invested in a Nigerian e-commerce

startup, bought troubled commercial real-estate loans in New

Zealand and backed Mexico's fastest-growing fintech lender.

It commonly lends to distressed companies, exacting terms that

boost its profits and limit its potential losses. A recent loan to

a struggling California turbine maker carries a 13% interest rate

and requires the company to set aside $12 million in cash as

collateral -- 40% of the value of the loan.

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 12, 2019 15:58 ET (19:58 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

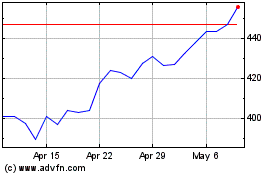

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

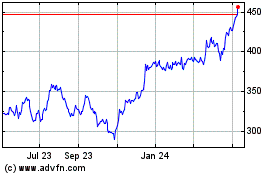

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024