By Tatyana Shumsky and Ezequiel Minaya

General Electric Co.'s bet on selling long-term care insurance

policies, which ballooned into a $16.5 billion liability,

underscores how policies meant to pay for nursing homes and

prescription costs have become one of the most unpredictable

segments of the insurance industry.

GE's skyrocketing liability is but only one example of an

industrywide lapse in judgment when assessing the future cost of

such care, industry experts said. Prudential Financial Inc., which

stopped issuing long-term care insurance in 2012, recorded a $1.5

billion charge related to its portfolio in the second quarter.

Genworth Financial Inc., which is among the roughly dozen companies

still offering this type of insurance, has incurred more than $3

billion in losses stemming from these plans.

GE in January reported a $6.2 billion charge linked to

liabilities for long-term care insurance policies, which prompted

federal regulators to expand a probe into the company's accounting

practices. The company has said it is cooperating with

investigators.

The Wall Street Journal reported Friday that former GE employees

told federal investigators that the company failed to acknowledge

worsening results in the insurance business.

GE also faces shareholder lawsuits alleging that it understated

risks related to its insurance operations.

"We are exploring every option to manage and mitigate risk from

the company's legacy insurance liabilities," said a GE spokeswoman,

who declined to comment on specifics of ongoing legal matters. "We

have a strong commitment to integrity in our controllership and

financial reporting."

Insurers make the bulk of their money from the premiums charged

to policyholders and from investing those premiums before paying

out claims. Forecasting the future payout for long-term-care

policies can prove particularly difficult.

That calculation involves census data, actuarial science and

mortality rates, among other mercurial variables. But it also

requires guesswork around the future price of health care.

"Assisted living, health care and prescriptions -- the inflation

rate in those things is massive," said Peter Bible, a partner and

chief risk officer at accounting firm EisnerAmper LLP.

Muddying the math is the unpredictable nature of regulation,

which could affect the portion of costs shouldered by the

government. "It's very complicated science," said Mr. Bible, a

former chief accounting officer at General Motors Co.

In recent decades, many long-term care plan providers

underestimated the payouts they would face when plans came due and

didn't charge high enough premiums. Companies also misjudged how

long claims would be paid out as consumers lived longer.

Moreover, the low interest-rate environment during the past

decade has dented the investment returns of insurance

companies.

"Who could have predicted interest rates would have been this

low for this long," said Jesse Slome, executive director of the

American Association for Long-Term-Care Insurance.

The dozen companies that offer a long-term care product include

Northwestern Mutual, Mutual of Omaha and Transamerica Corp.,

according to Mr. Slome, down from about 75 in the 1980s, when

long-term-care insurance became popular.

Insurance companies have recorded more than $28 billion in

charges related to long-term care insurance policies since 2007,

according to estimates by analysts at investment bank Evercore

ISI.

Changes in GE's risk assessment and assumptions triggered a $6.2

billion charge related to the insurance portfolio, the company

explained in a January conference call. At the time, GE estimated

it will need to contribute roughly $15 billion to its insurance

business over the next seven years.

GE stopped selling long-term care policies in 2006, but the

company hadn't reassessed the assumptions behind the likely risks

of these plans until 2017, said Ryan Zanin, GE Capital's chief risk

officer at the time, during the call.

GE Capital is the company's financial services unit. Mr. Zanin

left GE in June to pursue opportunities outside the company, a GE

spokeswoman said.

GE performed an annual test to ensure future premiums and

reserves would cover future claims, as required by regulators.

Because the company cleared the hurdle in previous years, it had to

leave in place existing risk assumptions, Mr. Zanin said on the

call.

That changed in 2017, however, when a surge in claims by one

segment of GE's insurance portfolio triggered a review. The

policyholders in that block were approaching 80 years or older,

when the bulk of claims tend to arise, Mr. Zanin said.

"Virtually, the entire industry has experienced greater claims

than originally anticipated where more people go on claim and for

longer than expected," he said on the call.

Prudential's charge, reported in August, followed a similar

annual review of the profitability of its remaining long-term care

portfolio. A Prudential spokesman declined to comment.

Genworth Financial, which was spun off from GE in 2006, has

incurred a cumulative statutory net loss of over $3 billion as of

Sept. 30, stemming from its legacy long-term care insurance

business.

Genworth continues to lose hundreds of millions on these legacy

blocks each year, a company spokeswoman said.

The company evaluates its assumptions annually and has taken a

proactive approach to premium increases, achieving approximately

$10 billion in approved rate increases on some of its newer

products, the spokeswoman said. The company is also working with

regulators to adopt a system of re-rating long-term care premiums

annually, in a way that is similar to how insurers adjust premiums

on homeowners, auto and health insurance, the spokeswoman said.

GE is seeking ways to mitigate its exposure to long-term care

insurance, the company's executives have since said.

GE was expected to perform in the fourth quarter the annual

reserves-adequacy test, the inputs for which were reset last year.

In advance of that, GE management anticipated an additional capital

infusion of $3 billion into the insurance business in 2019, GE

finance chief Jamie Miller said on an earnings call in October.

Write to Tatyana Shumsky at tatyana.shumsky@wsj.com and Ezequiel

Minaya at ezequiel.minaya@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 03, 2018 14:01 ET (19:01 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

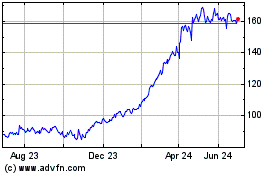

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

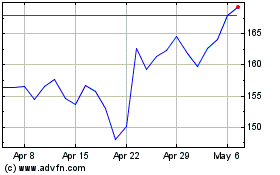

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024