By Jess Bravin and Brent Kendall

WASHINGTON -- The Supreme Court ruled Monday that defendants

can't be convicted of serious crimes under the Constitution unless

jurors are unanimous, overturning laws in two states and calling

thousands of verdicts into question.

But the court's fractured ruling has little significance for

cases outside Louisiana and Oregon, the only states where a 10-2 or

11-1 jury can convict. Instead, the justices' remarks about

precedent -- an issue of increasing importance, as the

abortion-rights decision Roe v. Wade and other liberal landmarks

face challenges -- may be the decision's most significant

legacy.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote Monday's opinion, overturning a

splintered 1972 decision that had left the two states' jury rules

intact.

The Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial always has required

unanimous verdicts, Justice Gorsuch wrote, a principle tracing back

through centuries of English law and recognized explicitly by the

Supreme Court in the 19th century. Such was the case in Louisiana

as well until the state's Jim Crow constitution of 1898. It adopted

the 10-2 jury to prevent the occasional African-American who made

it onto a jury from interfering with a white majority determined to

convict, the court observed.

The court rejected a challenge to that practice in the 1972

case, Apodaca v. Oregon, with a plurality opinion finding no

constitutional problem with a nonunanimous jury. To overrule that

case, Justice Gorsuch rejected the reasoning of his mentor who

wrote the decision, the late Byron White.

Justice White had argued that an "impartial jury" existed, in

the modern era, to "safeguard against the corrupt or overzealous

prosecutor and against the compliant, biased, or eccentric judge."

That could be something that could be accomplished with a 10-2 vote

as well as a unanimous one, he wrote.

Justice Gorsuch wrote that since the framers understood verdicts

to require unanimity, "as judges, it is not our role to reassess"

the wisdom of that choice. "With humility, we must accept that this

right may serve purposes evading our current notice," he wrote.

Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor

and Brett Kavanaugh joined all or part of the Gorsuch opinion,

while Justice Clarence Thomas agreed with the outcome through a

different legal framework.

Justice Samuel Alito dissented, joined in whole or part by Chief

Justice John Roberts and Justice Elena Kagan. Justice Alito wrote

that the racist and nativist motivations that led to the initial

adoption of the jury rules were irrelevant, since they were

readopted through processes that weren't similarly tainted.

Moreover, he warned, the past 48 years have seen Louisiana and

Oregon conduct "thousands and thousands of trials under rules

allowing non-unanimous verdicts. Now, those States face a potential

tsunami of litigation on the jury-unanimity issue" and when it

should apply retroactively to existing convictions.

Still, both Louisiana and Oregon already have been moving away

from the nonunanimous-jury rule. Louisiana voters abolished it for

future cases, while Oregon is expected to amend its constitution to

the same end, according to a brief from that state.

The most significant aspects of the decision, therefore, may

turn out to be the implications for the weight the court ascribes

to precedent in future cases.

Justice Kavanaugh has wrestled with that issue before and on

Monday published a three-part test for evaluating when prior cases

should be overturned.

To do so, he wrote, the precedent must be "egregiously wrong,"

should have "significant negative jurisprudential or real-world

consequences" and shouldn't "unduly upset reliance interests" -- or

the behavior of individuals, businesses and others based on the

expectation that the precedent accurately describes the law.

The immediate victor in Monday's case was Evangelisto Ramos, who

was sent to prison without possibility of parole after a 10-2 jury

convicted him of the 2014 stabbing murder of Trinece Fedison, with

whom prosecutors said he had been "sexually involved."

"We are heartened that the Court has held, once and for all,

that the promise of the Sixth Amendment fully applies in Louisiana,

rejecting any concept of second-class justice," said Ben Cohen, an

attorney for Mr. Ramos and with the Promise of Justice Initiative,

a New Orleans nonprofit.

"Louisiana's law was based upon a previous Supreme Court ruling

that allowed for non-unanimous juries," the Louisiana attorney

general's office said. "Our law has since been changed and the

Supreme Court has now issued this new ruling, yet our focus remains

the same: to uphold the rule of law and protect victims of

crime."

In a separate decision Monday, the court addressed the cleanup

of hazardous waste sites, limiting the ability of landowners to use

private ligation to force restoration measures beyond those

required by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The case dates from 2008, when a group of 98 Montana property

owners sued Atlantic Richfield Co., a BP PLC subsidiary. The

landowners alleged the company needed to do more than the federal

government required to remediate arsenic and lead pollution in

lands surrounding a copper smelting operation near Butte.

The EPA, under the federal Superfund law, has been managing

cleanup of the site for 35 years, and Atlantic Richfield has spent

roughly $450 million so far implementing the agency's orders.

The landowners filed suit in state court to seek roughly $50

million more for property restoration. The high court, in a 7-2

opinion by Chief Justice Roberts, didn't entirely foreclose such

lawsuits but said landowners need EPA's blessing first.

The plaintiffs don't have EPA's approval, and the government has

said the landowners' plans could interfere with its cleanup,

including by digging up contaminated soil that has been

protectively capped in place.

Chief Justice Roberts took issue with the landowners' claim that

requiring EPA approval would mean they'd need a nod from the feds

even to dig out part of their backyards to make a sandbox for

grandchildren.

"The grandchildren of Montana can rest easy," the chief justice

wrote.

In dissent, Justice Gorsuch accused the court of stripping

rights from landowners and forcing them to live with toxic

waste.

"The implication here is that property owners cannot be trusted

to clean up their lands without causing trouble," Justice Gorsuch,

joined by Justice Thomas, wrote.

Write to Jess Bravin at jess.bravin@wsj.com and Brent Kendall at

brent.kendall@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 20, 2020 18:20 ET (22:20 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

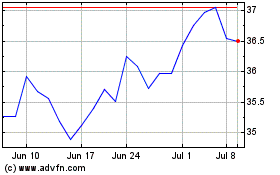

BP (NYSE:BP)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

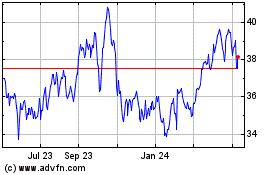

BP (NYSE:BP)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024