The investment giant fires a fund manager whose daughter got a

part in a movie he financed

By Jason Zweig

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (February 29, 2020).

Take a break from the market turmoil to ponder the drama at a

little fund run by the world's biggest asset manager. It involves

allegations of fraud and forgery, not to mention a fund manager's

daughter landing a part in a movie the fund financed.

We're talking about the BlackRock Multi-Sector Income Trust. In

2017, the fund, which at that time had $750 million in net assets,

lent a tenth of that to a small, privately held movie company,

Aviron Capital LLC. It was an unusually aggressive bet. By late

2019, the fund said the loan wasn't worth anything, for a nearly

$75 million loss. In December, it filed a lawsuit against Aviron

and its owner, William Sadleir.

Mr. Sadleir denies committing fraud. He does, however, admit

copying-and-pasting signatures of a BlackRock fund executive onto

documents to accelerate the sale of $3.2 million in movie-revenue

receivables on which the fund had exclusive claim.

"I should not have done it," Mr. Sadleir said in an interview

this week. "It was bad judgment on my part. I know better."

Why did the mighty BlackRock lend so much money to a small movie

venture in the first place?

That question matters because giant investment firms should have

fail-safe procedures in place to prevent conflicts of interest and

to prevent fund managers from making arbitrarily big bets.

It also matters because investors buy a bond fund to earn steady

income, not to risk losing their principal. Multi-Sector Income

Trust has lost 3% in the past three months, while the bond market

has earned a positive 3% return, according to Morningstar. The fund

was outperformed by more than 99% of its peers over the past year,

largely because of the failed bet on Aviron.

And BlackRock charges an arm and a leg for this fund -- total

management expenses of 1.4% in 2019 -- in part to cover the costs

of carefully researching its investments. That's 22 times as much

as the firm's cheapest exchange-traded bond funds, which don't

bother researching individual holdings at all.

What's more, BlackRock, under Chief Executive Laurence Fink, has

set itself out in recent years as an arbiter of corporate

conduct.

In a twist right out of a Hollywood screenplay, Aviron, the

movie company financed by this BlackRock fund, cast the daughter of

one of the fund's managers in one of its films.

As a result, the firm fired the manager, Randy Robertson,

earlier this week after an extensive internal investigation,

according to a BlackRock spokesperson.

In a statement, BlackRock said its fund was "a victim of fraud

perpetrated by Aviron and its principal." The firm added that it is

taking "vigorous steps" to recover value for the fund's

shareholders and is moving to "enhance the level of oversight and

due diligence related to these types of transactions."

Mr. Robertson couldn't be reached for comment. His daughter,

actress Rebecca Lee Robertson, declined to comment.

BlackRock first invested in Aviron with a $12 million loan in

2015. Soon after, "we arranged for [Ms. Robertson] to meet with

casting agents and managers," says Mr. Sadleir. "Anytime there was

an opportunity to put her in a movie, we considered her."

Mr. Sadleir told me this week that Mr. Robertson agreed to

release $10 million in financing for " After," a 2019 movie from

Aviron, after the BlackRock manager learned his daughter would have

a speaking role in the film.

"I can't tell you that he made the decision purely because his

daughter was in the movie," says Mr. Sadleir, "but I can tell you

BlackRock approved that financing after turning down the

opportunity to finance several earlier movies."

Under Mr. Sadleir, Aviron has released seven films -- six

financed by the BlackRock fund -- including some notable successes.

"Kidnap," with Halle Berry, released in 2017, grossed an estimated

$35 million at the box office worldwide. Although Mr. Sadleir says

"A Private War," released in 2018, hasn't yet earned a lot of

money, it was critically acclaimed.

Mr. Robertson, a 10-year veteran of BlackRock, was the firm's

head of securitized assets, as well as co-manager of this fund. His

conduct in relation to the Aviron investment violated BlackRock's

conflict-of-interest policy, the firm said.

The BlackRock fund's investment in Aviron was unusual.

First, the commitment was extraordinarily large. In July 2017,

the fund put 10% of its net assets into Aviron. No other single

corporate issuer accounted for nearly as much of its assets at the

time. No other BlackRock fund has ever invested in Aviron, says a

BlackRock spokesperson.

Then there's Mr. Sadleir.

He served as a special assistant to the president and a deputy

secretary of state under President Ronald Reagan. He founded Dayna

Communications Inc., a networking-technology company that was

acquired by Intel Corp. in 1997. He has been in the movie business

for a decade.

However, Mr. Sadleir has had prior disputes with creditors.

A nonprofit he ran was sued in a Norwegian court in 2002 over

allegations of unpaid bills and debt. The action was later settled

by an unrelated third party. A 2015 lawsuit in California alleged

Mr. Sadleir had "misappropriated more than $3 million in

collateral," and that court in 2019 entered a judgment against him

personally for $2.7 million.

Mr. Sadleir had his own explanations for these cases, telling me

there was no misappropriation of monies.

With these disputes in the public record, why did the BlackRock

managers regard Mr. Sadleir and Aviron as a good credit risk and a

plausible bet for a tenth of the fund's assets?

One explanation: The debt was not only collateralized by

Aviron's assets, but CBL Insurance Ltd. of New Zealand also

guaranteed full payment of principal and interest, according to Mr.

Sadleir and BlackRock. What's more, motion-picture revenues tend

not to move in tandem with the stock market or other financial

assets, making the Aviron debt a potentially good diversifier.

Unfortunately, CBL Insurance became insolvent and was liquidated

by the New Zealand government late in 2018, voiding its guarantee

of the Aviron loan.

Mr. Robertson drove the decisions about the Aviron investment

all along, according to Mr. Sadleir, who says the fund manager

brought his daughter to the earliest business meeting between

BlackRock and Aviron at the movie company's offices in Los Angeles

back in 2015.

Proponents of so-called alternative assets say that such

non-traded investments offer the potential for lower risk and

higher return. As the private loan to Aviron demonstrates,

alternatives also offer greater potential for conflicts of interest

that can be difficult to detect before it's too late.

Investors should always be wary whenever a fund puts more than a

few percentage points of its assets into an obscure investment that

doesn't trade, where the sunlight can take so long to reach. If

something like this can happen at BlackRock, it can happen

anywhere.

Write to Jason Zweig at intelligentinvestor@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 29, 2020 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

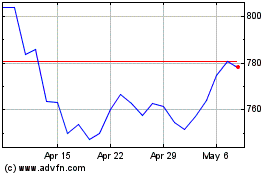

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

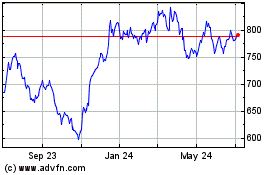

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024