By Gregory Zuckerman, Julia-Ambra Verlaine and Paul J. Davies

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (March 13, 2020).

Treasury prices extended their declines Thursday while U.S.

stock indexes suffered their worst losses since 1987 -- an unusual

dual downturn that raised concerns that the Wall Street rout is

entering a painful new stage: The forced unwind of a number of

popular trading strategies, some of which involve leverage, or

borrowed money.

The Dow industrials dropped 2,352 points, or 10%, bringing their

decline to 27% in the month since the last record high. The yield

on the 10-year Treasury note, which hit a record low Monday at

0.501%, rose to 0.842%. Bond yields rise when prices fall.

Sharp stock declines aren't unusual, particularly at a time of

economic stress following a long bull market. But the sight of bond

and stock prices declining sharply together unnerved some traders,

suggesting further selling could follow in response to margin

calls, risk limits at banks and investment firms, and other

factors. Also surprising investors: Gold, a traditional haven,

dropped 3%, marking its third straight decline.

"There was nowhere to hide today with stocks, bonds and gold all

hit hard," said Jonathan Krinsky of Baycrest Partners LLC.

The latest carnage came even after the Federal Reserve said it

would inject more than $1.5 trillion into Wall Street on Thursday

and Friday to prevent ominous trading conditions from creating a

sharper economic contraction.

Investors view the Fed intervention as providing relief to banks

facing demands for cash, as economic shocks force companies to tap

credit lines and draw down revolving loans.

The Fed's action marks an effort to interrupt what some analysts

and investors view as a dangerous negative-feedback loop, in which

market declines beget further declines, even absent changes in

financial and economic fundamentals.

But the Fed announcement only paused the selling, adding to

concerns in the market involving two long-running trades: The

"basis trade," which seeks to exploit pricing gaps between Treasury

securities and futures, and "risk parity funds," which try to score

strong performance with moderate risk using futures contracts that

can boost the returns of low-risk assets.

On Thursday morning, Bank of America warned clients that the

unwind of several leveraged trading strategies risked creating "a

cascading effect whereby U.S. Treasury yields rise sharply and

force liquidations from other similar investors."

Thanks to the disruption of short-term funding, securities

dealers could be left with $300 billion of 30-year Treasurys on

their books whose ultimate sale would cause U.S. Treasury yields to

rise sharply, potentially forcing further unwinds and worsening

conditions throughout financial markets, analysts at Bank of

America and JPMorgan say.

The risk parity strategy is intended to adapt to market

conditions and be a one-stop shop for investor assets. Firms

including Bridgewater Associates LP and AQR Capital Management LLC

are the leading investors in the strategy. Bridgewater founder

Raymond Dalio says he helped invent the risk-parity category nearly

two decades ago and in the past has told clients he has the

majority of his net worth invested in the strategy.

A spokesman for Bridgewater wouldn't comment.

Risk-parity investors, who manage about $175 billion, according

to industry estimates, usually buy futures tied to the performance

of bonds, stocks and commodities. They use risk metrics to

determine the proper allocations to various markets, shifting

assets to maintain an equal distribution of risk. The goal of these

funds: Somewhat higher returns with the same amount of risk of

other investment classes.

The key to the trade is assessing the volatility of each asset

class. If stocks are determined to be three times as volatile as

Treasury bonds, an investor would put three times as much in bonds

as in stocks, for example. As stock volatility increases, as it has

lately, a risk-parity portfolio manager would sell some stocks --

something that has been happening in recent weeks -- adding

pressure on the overall stock market, risk-parity traders say.

And if bonds or other safer asset classes also come under

pressure and become more volatile, as has also been happening this

week, they'd sell those as well, incurring losses along the

way.

Risk-parity specialists say the bond losses haven't been enough

to cause true pain, and that the broader concerns about the

strategy are unfounded.

"Risk parity is not big enough, doesn't trade enough, and

doesn't trade quickly enough to ever be noticeable in the movements

of stock or bond markets," says Michael Mendelson, a principal at

AQR.

The AQR Multi-Asset fund is down 6.63% this year through

Wednesday, and was down 2% Thursday, topping the overall market.

The S&P 500 is down 27% in 2020.

In the view of many in the markets, the underlying key factors

are the scarce liquidity in many markets, which is causing prices

to move sharply, and the prevalence of technical trading driven by

trends in a few key gauges including certain prices and measures of

volatility.

One such gauge is the value-at-risk framework, used at many

banks and investment firms to judge the likely losses they would

face in any single day under certain stated conditions. Some

analysts say that when volatility is high, this value at risk, or

VaR as it is known, increases -- prompting firms to sell riskier

assets in a bid to reduce the risk of their position.

Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou, global markets strategist at JPMorgan

Chase & Co., said that much of the widespread selling of all

kinds of assets in recent days has been driven by risk management

rather than any fundamental view on the economy or securities

prices.

"With the lack of liquidity in markets, one thing is feeding the

other," he said.

The main measure of stock market volatility is the Cboe

Volatility Index, or VIX, which on Thursday approached levels last

seen in 2008. A high reading on the VIX can cause some investors to

breach their risk limits and become forced sellers, Mr.

Panigirtzoglou said.

Investors also said the market was losing faith in political

leaders in some countries to tackle the coronavirus, or in policy

makers' ability to support markets and the economy with rate cuts

or other stimulus.

"It's become that kind of liquidation where you see people sell

what they can and move to cash," said David Riley, chief investment

strategist at BlueBay Asset Management.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 13, 2020 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

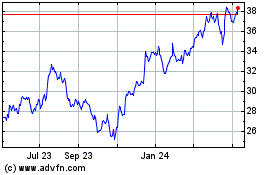

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

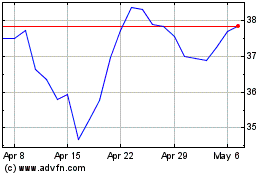

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024