By Julia-Ambra Verlaine and Nick Timiraos

The deepening Wall Street rout is adding to pressure on U.S.

banks, as the retreat of investors from risky assets saddles

lenders with securities they are struggling to sell at desired

prices.

The crunch has been evident in the share prices of the largest

U.S. financial firms, which have fallen 30% or more in many cases

over the past month. Citigroup Inc. dropped 8.6% on Wednesday,

extending its decline to 36%, nearly doubling the drop in the

S&P 500.

Now the pain is spreading, as fears about the coronavirus's

impact on economic activity intensify and as an oil-price war brews

between Saudi Arabia and Russia. Traders, analysts and regulators

are monitoring markets for signs that problems there are spilling

over to hurt the real economy, by constraining lending.

Executives in meetings with President Trump said Wednesday the

industry remains in ruddy good health. Brian Moynihan, chief

executive of Bank of America Corp., said banks are in "great

position" on capital and liquidity. Michael Corbat, chief executive

of Citigroup, said "this is not a financial crisis."

But amplifying the uncertainty Wednesday was news from across

industries. Boeing Co. drew down a $13.8 billion loan with many

banks, and companies owned by some private-equity firms are being

encouraged to take similar action, according to news reports. Such

moves could further stretch funding and balance-sheet concerns at

banks.

"When markets come under duress as they have over the past

couple of weeks, asset prices are pushed to levels where you begin

to see margin calls and other internal activity that is not always

visible on the surface," said Daniel Deming, a managing director at

Chicago-based KKM Financial.

The most surprising development for traders Wednesday: the sharp

decline in the price of U.S. Treasury securities, which until this

week had consistently risen significantly on days when U.S. stocks

were falling. The price declines sent yields higher after dropping

to record lows and were fueled in part by banks selling U.S.

government securities to reduce inventories and raise cash. Rates

are low enough that Wednesday's action itself didn't hurt banks,

but the unusual nature of the move raised eyebrows.

People familiar with some of the largest securities-dealing

banks said many firms bought corporate bonds as prices fell last

week, but those purchases resulted in some banks having balance

sheets that executives deemed too large. With prices barely having

recovered in many markets, some banks chose to sell Treasurys

instead, in part reflecting their significant appreciation in

recent weeks.

Another area of worry: the rising price difference between a

Treasury bond and the equivalent future, also known as the

"cash-future basis." Traders said the dislocation was the worst

since 2008 and reminded some of an even more acute episode in 2001

following the 9/11 attacks. Analysts and portfolio managers

scrutinize the basis because signs of stress there can foretell

lending pullbacks.

Trading conditions in the Treasury market "are certainly

deteriorating, but it's not miserable," said Jim Vogel, an

interest-rate strategist at FHN Financial. "The system is just

overloaded" as investors digest rapid changes in sentiment, news

about possible stimulus from Washington and financing

challenges.

Similarly, the spread between the two-year Treasury yield and

the overnight indexed swap, a derivative used by banks to hedge

exposures created in lending and investing, has risen this week,

including an increase of 0.05 percentage point on Wednesday.

"Swap spreads are showing early signs of dealer balance-sheet

funding pressures," said Priya Misra, head of global rates strategy

at TD Securities.

Mortgage lenders said a lack of bidding activity for mortgage

bonds in credit markets led rates to rise, with quoted prices on

the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage increasing to 4.375%, more than a

percentage point higher than the record lows it had plumbed last

week.

The share-price declines and funding-market stresses don't

necessarily indicate that Wall Street is questioning the viability

of the banking system, as it did in the 2008 crisis. Following that

episode, banks significantly boosted their capital cushions and

access to cash under regulatory scrutiny and financial

legislation.

But changes in regulation and shifts in the economy have reduced

the market's capacity to absorb volatility, many traders say, and

the declines in bank-related markets in part reflect concerns about

how a test of the new regime might play out for some lenders.

The cost to insure bank bonds against default rose sharply,

suggesting investors are worried about a funding pinch. The cost of

insuring against default on Citigroup debt for five years rose to

$115,000 annually from $40,000 this week, according to FactSet,

though it remains well below the panicked pricing seen in 2008.

Adding to those concerns were additional ructions in the market

for repos, the repurchase agreements that serve as a short-term

funding mechanism for many financial firms.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York said Wednesday it would

ratchet up the amount of cash it injects into money markets

beginning Thursday through collateralized loans known as repurchase

agreements, or repos. It increased the amount of overnight repo

offerings to $175 billion from $150 billion. It will also offer $50

billion in one-month loans on Thursday and again on March 16 and

March 23.

Those transactions will boost to more than $500 billion the

amount of cash the Fed is providing through such repo lending,

using a mix of overnight, two-week and four-week loans, expanding

its $4.2 trillion asset portfolio to levels last seen in 2017. Repo

lending outstanding from the Fed dropped to a low of $126.2 billion

on Feb. 28.

Mr. Vogel said the Federal Reserve could help calm markets by

increasing its purchases of Treasury bills, which it has been doing

at a pace of $60 billion per month since separate problems first

flared in short-term lending markets last fall. That would free up

resources from broker-dealers to finance other securities rather

than Treasury bill auctions.

Mr. Vogel also said the Fed could slow the runoff of its

holdings of mortgage-backed securities as another pressure-release

valve. Currently it allows up to $20 billion in mortgage bonds to

mature from its $4.2 trillion bond portfolio every month.

Get an early-morning coronavirus briefing each weekday, plus a

health-news update Fridays: Sign up here.

Write to Julia-Ambra Verlaine at Julia.Verlaine@wsj.com and Nick

Timiraos at nick.timiraos@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 11, 2020 20:24 ET (00:24 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

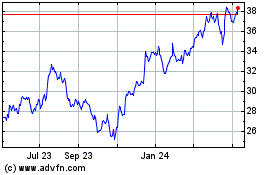

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

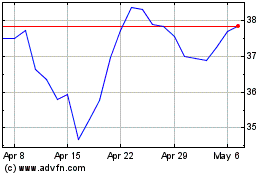

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024