By Andy Pasztor and Andrew Tangel

Potentially hazardous wiring inside Boeing Co.'s 737 MAX jets is

the latest flashpoint between U.S. and European regulators and a

further complication in the grounded fleet's return to service,

according to people familiar with the details.

Technical experts at the European Union Aviation Safety Agency

want certain electrical wires relocated to reduce what they say are

dangers from potential short circuits, which in a worst-case

scenario could disrupt flight-control systems, according to these

people.

In addition to the Federal Aviation Administration's ongoing

safety review of proposed fixes to the MAX, the European agency is

independently vetting such changes.

But engineers at the Chicago plane maker and high-ranking FAA

managers, including the agency's top safety official, contend

moving the wiring isn't necessary, one of these people said. Boeing

hasn't yet submitted its formal recommendation, though the issue is

headed for a decision in the next few weeks by FAA head Steve

Dickson.

The disagreement over whether to take action on the wiring,

which hasn't been reported before, has prompted the FAA to hold off

scheduling a key certification flight for the MAX. It also

highlights the emergence of a series of new technical challenges

and delays confronting the Chicago plane maker as it strives to get

the MAX back in the air world-wide. The planes have been grounded

since last March, following two fatal crashes that killed 346

people.

The planes are expected to gradually start resuming commercial

flights sometime in the summer, with major U.S. carriers having

removed them from schedules until June.

On Saturday, the FAA released a statement saying Boeing recently

informed the agency "about concerns associated with the location of

wiring in certain areas of the MAX." Since then, according to the

statement, "the FAA has closely monitored the company's analysis

and how the issue might affect the ongoing certification efforts."

The wiring concerns were reported earlier by the New York

Times.

Reiterating earlier statements, the FAA said the MAX will be

approved to carry passengers again "only after our safety experts

are fully satisfied that all safety-related issues are

addressed."

A Boeing spokesman said the company is cooperating with

international regulators on a thorough certification process, "and

we are working to perform the appropriate analysis." He said, "It

would be premature to speculate as to whether this analysis will

lead to any design changes."

A spokeswoman for EASA, which also hasn't submitted its final

position to the FAA, declined to comment. The issues still could be

resolved with a compromise, but Boeing's priority at this point,

according to some of the people familiar with the details, is

avoiding any wire modifications.

The wires, which help control movable panels on the tail and

power other systems, may be too close to each other in a dozen

locations from the rear of the aircraft to the main electronics

compartment beneath the cabin and behind the cockpit, according to

the people familiar with the issue.

A short circuit, or "arcing" of electrical current between

wires, could cause control problems for pilots that the FAA

characterizes as hazardous or in some cases even catastrophic,

according one of the people briefed on the details.

EASA and FAA technical experts, along with some other FAA

officials responsible for certifying aircraft designs, have taken

the position that safety rules require wiring modifications in such

instances, this person said.

The relevant international rules relate to safety enhancements

put in place more than a decade ago after an in-flight fire caused

a Swissair jet to plunge into the water near Nova Scotia in 1998,

killing all on board.

The current concerns about potential wiring problems stem from

Boeing's analysis of how short circuits could cause problems with

some flight-control systems, and how quickly pilots could react to

those emergencies.

Since the two fatal crashes, safety regulators have been

reassessing certain MAX flight-control systems, changing software,

adjusting related computers and modifying pilot training.

Last month, industry and government officials revealed the

latest software glitch, a problem that prevents the jet's

flight-control computers from powering up and verifying they are

ready for flight, and said Boeing was working to resolve it.

Addressing the wiring issues would pose tough logistical and

financial hurdles. How the agency mandates fixes may depend on who

owns the aircraft, according to another person familiar with the

details. The FAA may require Boeing to fix wiring on approximately

400 undelivered aircraft now in storage at airfields dotting the

Puget Sound area, this person said.

For planes previously delivered to carriers, the agency would

likely perform a risk analysis to determine whether the wiring

should be repaired either before the planes fly again or during

routinely scheduled maintenance, this person added.

Relocating the wiring bundles would take roughly two weeks per

plane, according to industry and government experts. Such fixes

could be performed at the same time as software and training

updates, depending on available manpower, to try to minimize

additional delays.

Write to Andy Pasztor at andy.pasztor@wsj.com and Andrew Tangel

at Andrew.Tangel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 01, 2020 23:11 ET (04:11 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

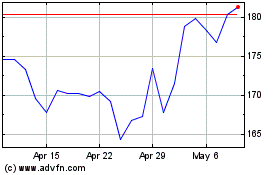

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024