By Andy Pasztor and Andrew Tangel

LE BOURGET, France -- Efforts to get Boeing Co.'s 737 MAX

jetliners back in the air have been delayed in part by concerns

about whether the average pilot has enough physical strength to

turn a mechanical crank in extreme emergencies.

The concerns have made the crank -- which moves a horizontal

panel on the plane's tail -- the focus of engineering analysis,

simulator sessions and flight testing by the plane maker and U.S.

air-safety officials, according to people familiar with the

details. The extent of the internal debate hasn't been previously

reported.

Use of the crank is intended as the final step in an emergency

checklist to counteract dangerous movements of the tail's

horizontal stabilizer, such as those involved in two fatal crashes

of MAX aircraft when an automated flight-control system

malfunctioned.

Turning the crank to adjust the horizontal stabilizer can help

change the angle of the plane's nose. Under certain conditions,

including at unusually high speeds with the panel already at a

steep angle, moving the crank can take a lot of force. Among other

things, the people familiar with the details said, regulators are

concerned about whether female aviators -- who typically have less

upper-body strength than their male counterparts -- may find it

difficult to turn the crank in an emergency.

The analysis could have even wider significance because the same

emergency procedure applies to the generation of the jetliner that

preceded the MAX, known as the 737 NG. About 6,300 of these planes

are used by more than 150 airlines globally and they are the

backbone of short- and medium-range fleets for many carriers.

Neither Boeing nor regulators anticipate design or equipment

changes to result from the review, these people said. But the issue

has forced a reassessment of some safety assumptions for all 737

models, as previously reported by The Wall Street Journal.

The global MAX fleet of about 400 planes was grounded in March,

following two fatal nose-dives triggered by the misfiring of an

automated flight-control system called MCAS. The two crashes killed

a total of 346 people.

There are no plans to restrict certain pilots from getting

behind the controls of any 737 models based on their strength,

according to people with knowledge of the deliberations. But both

Boeing and Federal Aviation Administration leaders are concerned

that if discussions of the matter become public they could be

overblown or sensationalized, according to industry and government

officials familiar with the process.

All underlying safety questions about the 737 MAX have to be

resolved before the FAA can put the grounded fleet back in the air,

according to U.S. and European aviation officials.

In response to questions, a Boeing spokesman said: "We will

provide the FAA and the global regulators whatever information they

need." Previously, Boeing said it is providing additional

information about "how pilots interact with the airplane controls

and displays in different flight scenarios."

Speaking before the Paris Air Show here this week, Boeing Chief

Executive Dennis Muilenburg said he wanted to conduct an

"end-to-end, comprehensive review of our design and certification

processes," as well as other matters.

An FAA spokesman declined to comment on specifics. Acting FAA

chief Daniel Elwell has said the agency is pursuing a complete

investigation of the two MAX crashes, including examination of

emergency procedures, training and maintenance.

FAA experts also aim to study how issues regarding pilot

strength were dealt with during certification approvals of older

versions of the 737, according to the people familiar with the

specifics.

Simulator sessions and flight tests have measured the strength

required to turn the crank in various flight conditions for pilots

of both genders, according to two of the people briefed on the

details.

In a flight-simulator test earlier this month, Journal columnist

Scott McCartney and pilot Roddy Guthrie, fleet captain for the 737

at American Airlines, experienced troubles in turning the wheel. As

described in a June 5 article, Capt. Guthrie couldn't move the

wheel until Mr. McCartney pitched the plane's nose down, easing

some of the pressure on the wheel. See how the wheel works in this

WSJ visual about the two crashes.

Government and industry experts are considering possible

operational, training and pilot-manual changes to resolve safety

concerns about the procedure, according to the people familiar with

the specifics. The results are expected to be part of a package of

revised software and training mandates that the FAA is seen issuing

later this summer.

Capt. Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger, the retired US Airways pilot

celebrated for his 2009 "Miracle on the Hudson" landing, said

Wednesday that pilots should be required to spend time in

simulators before the MAX returns to service, not only to review

the updates to the MCAS software but to practice situations where

manually turning the crank would be more challenging. At higher

airspeeds, turning the wheel could require two hands, the efforts

of both pilots, or may not even be possible, he said.

"They need to develop a muscle memory of their experiences so

that it will be immediately accessible to them in the future, even

years from now, when they experience such a crisis," he said

Wednesday at a hearing of the House Committee on Transportation and

Infrastructure's aviation subcommittee.

Mr. Sullenberger told the committee that he recently experienced

a recreation of the fatal MAX flights in a flight simulator. He

came away from it understanding how crews could have been

overwhelmed by alerts and warnings without enough time to fix the

problem.

The former commercial pilot also expressed broader concern about

how the MAX was designed and certified by regulators. "It is clear

that the original version of MCAS was fatally flawed and should

never have been approved," Mr. Sullenberger said in written

testimony.

"The 737 MAX was certified in accordance with the identical FAA

requirements and processes that have governed certification of

previous new airplanes and derivatives," a Boeing spokesman said in

a statement. He also said the company continues to work on training

requirements with global regulators and airlines.

The pending software fix is intended to make it easier for

pilots to override MCAS, which moves the horizontal stabilizer to

point the nose down.

The FAA's testing comes after the agency prodded Boeing to draft

a new safety assessment covering MCAS as well as the related

emergency procedure, according to U.S. and European aviation

officials.

The FAA isn't alone in documenting the differences in average

strength between men and women in critical safety roles. The

Pentagon, for example, categorizes such information in assessing

the fitness of some uniformed personnel for certain

assignments.

--Alison Sider contributed to this article.

Write to Andy Pasztor at andy.pasztor@wsj.com and Andrew Tangel

at Andrew.Tangel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 19, 2019 18:32 ET (22:32 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

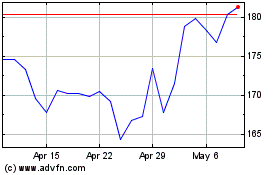

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024