By Andy Pasztor and Andrew Tangel

Federal investigators and lawmakers are asking the same question

about Boeing Co.'s 737 MAX jet: Did U.S. safety regulators

rigorously follow longstanding engineering and design standards in

approving a suspect stall-prevention feature?

Officials from the Justice Department and the Transportation

Department inspector general's office are looking into how Boeing

developed the aircraft, which has been involved in two fatal

crashes within five months. The inspector general's office is also

scrutinizing whether the Federal Aviation Administration took any

shortcuts compromising safety, people familiar with the matter

said. Boeing was eager to complete the design and certification

process as quickly as possible, according to people who were

involved.

Boeing has said the FAA certified the 737 MAX according to

identical requirements and processes for previous airplanes after a

six-year, methodical development.

House and Senate committees are separately gearing up to grill

senior FAA leaders next month about many of the same issues,

focusing on the stall-prevention system, which was created for the

737 MAX but not highlighted in pilot manuals or training.

Canada's transport minister, Marc Garneau, said Monday the

government would conduct its own certification of Boeing's promised

software modification to the stall-prevention system, even if it is

certified by the FAA.

Mr. Garneau also said Canada is reviewing its original decision

in 2017 to allow 737 MAX jets to fly in that country's airspace,

effectively replicating the FAA's safety approval. Canada last week

grounded the plane shortly before it was idled in the U.S.

"We're going to review the validation that we did at that time,"

Mr. Garneau said in Ottawa. "We may not change anything but we've

decided that it's a good idea for us to review" the decision.

Such a move is highly unusual, especially for a close U.S.

air-safety partner such as Canada, because governments world-wide

almost always accept the decision of the country where an aircraft

is manufactured. But as in the unilateral grounding of 737 MAX jets

earlier this month by a host of regulators overseas, the FAA's

influence regarding the MAX fleet has been waning.

The U.S. Transportation Department inquiry has included

questions about the aircraft's design, how training was devised and

whether safety was compromised in favor of business concerns, a

person familiar with the details said.

The FAA said the plane was approved to carry passengers as part

of the agency's "standard certification process," which the agency

said is "well established and (has) consistently produced safe

aircraft." The agency declined to comment on various decisions

regarding specific systems.

The Justice Department and the Transportation Department's

inspector general declined to comment.

A Boeing spokesman on Sunday said the Chicago-based company

wouldn't respond to questions on legal matters or governmental

inquiries. The spokesman didn't respond to requests to comment on

Monday.

As The Wall Street Journal reported earlier, a federal grand

jury in Washington, D.C., issued a broad subpoena dated March 11 to

at least one person involved in the 737 MAX's development, seeking

related documents, including correspondence, emails and other

messages.

Rep. Peter DeFazio of Oregon, the Democratic chairman of the

House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, said his panel

would delve into how the plane was developed and approved. "We're

going to investigate why retraining was not required," Mr. DeFazio

said in an interview after the FAA grounded the planes last week.

"What kind of pressure was applied or not applied?"

Interviews with former government and industry safety experts,

however, highlight potential areas where analyses of the

stall-prevention system, dubbed MCAS, might have deviated from the

FAA's typical safety-review process.

An important element of the Transportation Department review,

these officials said, is expected to be whether the FAA and Boeing

complied fully with traditional FAA design requirements for systems

that are essential to the safety of an aircraft.

Over the years, the agency has mandated the use of a formal,

structured approach to determine how a specific piece of equipment

or system failure should be categorized and scrutinized.

Under the FAA's process, systems that entail significant hazards

and potential loss of life if they go haywire are generally put

into two categories: those that have an "improbable" risk of

failure and those with an "extremely improbable" risk of

failure.

"Improbable" essentially means the part or system is unlikely to

fail during the lifetime of any individual airplane, according to

FAA documents and industry officials. An "extremely improbable"

failure is deemed so rare that it is unlikely to occur during the

lifetime of an entire fleet of aircraft.

Boeing, these officials said, apparently persuaded the FAA that

MCAS wouldn't have to meet the more-rigorous of those standards,

partly because a misfire could be counteracted by pilots simply

turning off the entire system.

A spokesman for Boeing said: "The FAA considered the final

configuration and operating parameters of MCAS during MAX

certification, and concluded that it met all certification and

regulatory requirements."

The need for MCAS arose as Boeing was creating the MAX, because

its large, fuel-efficient engines jutted forward in a way those on

earlier 737 models hadn't. That shifted the plane's balance,

tipping its nose up and making it tougher to fly in certain

conditions than the 737s that pilots world-wide knew how to handle.

To help pilots manage that difference, Boeing added a powerful new

stall-prevention system.

That solution, the stall-prevention system known as MCAS, was

designed to push the plane's nose down in certain conditions to

avoid the aircraft stalling, a loss of aerodynamic lift that can

result when a plane is climbing too steeply or with too little

power, leading to an uncontrolled plunge. But MCAS is now under

scrutiny after investigators determined pilots in the October crash

of Lion Air Flight 610 battled the system during the 11-minute

flight. U.S. and other authorities grounded the MAX after initial

data from this month's crash of a second jetliner, Ethiopian

Airlines Flight 302, pointed to potential similarities with the

Indonesian accident.

Boeing designed MCAS to rely on data from a single sensor that

measures the angle of the plane's nose, known as the angle of

attack. The idea was that a single sensor, rather than two, would

be simpler, a person familiar with the matter has said, and would

be in line with Boeing's long-held design philosophy of keeping the

pilot at the center of cockpit control.

But Boeing's design of the system puzzled some former employees,

safety experts and regulators. They saw it as a departure from the

company's typical practice of relying on multiple sensors to reduce

the risk of systems misfiring based on erroneous data from a single

faulty sensor.

"It seems odd given Boeing's traditions," said Frank McCormick,

a former Boeing flight-controls engineer who went on to be a

consultant to regulators and manufacturers on matters including how

such systems are designed. "It's not just as conservative as would

have been the norm in the old Boeing."

A Boeing spokesman said "design, development and certification

was consistent with our approach to previous new and derivative

airplane designs."

If the FAA had decided differently, a former regulator and an

industry air-safety expert said, Boeing probably would have been

forced to go with a design for MCAS that relied on two sensors,

instead of just one. An FAA document specifies that the possibility

of a given system failing cannot be designated "extremely

improbable" if it could result from a single faulty compon

An air-safety expert with decades of safety work and

accident-investigation experience criticized the notion that the

person flying the plane could provide the ultimate backstop in case

MCAS malfunctioned, saying: "A pilot only provides a redundant

safeguard if he or she has been properly trained to understand the

system."

Since the Lion Air crash, Boeing has emphasized that an existing

procedure that pilots are trained to follow would turn off the

stall-prevention system.

--Siobhan Hughes and Kim Mackrael contributed to this

article.

Write to Andy Pasztor at andy.pasztor@wsj.com and Andrew Tangel

at Andrew.Tangel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 18, 2019 20:00 ET (00:00 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

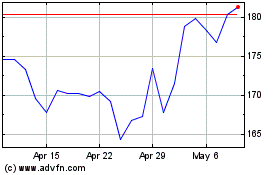

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024