By Jason Zweig

Back in Business is a new, occasional column that puts the

present day in perspective by looking at business history and those

who shaped it. Read the first installment here. Mr. Zweig's

Intelligent Investor column will return next week.

A hot stock doubles and then doubles again in a matter of weeks.

Thousands of people who have never invested in their lives suddenly

try to beat the market.

That isn't just a description of Tesla Inc. and day-trading

customers of the Robinhood smartphone app in 2020. It's also what

happened in 1720. Three hundred years ago, one of the biggest

manias in financial history was at its peak.

In the summer of 1720, shares in the South Sea Co. and other

leading stocks roared to all-time highs as speculators chased

instant profits. Ever since, this sudden outbreak of stock trading

has been known as " the South Sea bubble." Even faster than it

inflated, it burst -- and left us with lessons about human nature

that reverberate today.

From July 10 through July 12, 1720, South Sea shares perched at

GBP950, up 650% for the year. Royal Exchange Assurance and London

Assurance crested in late August, up an astonishing 1,243% and

4,220% for the year, respectively.

Then, in three catastrophic weeks in September, it all began

crashing down. By the end of 1720, these leading stocks had fallen

between 81% and 96% from their peak.

The losses were devastating because speculating had been so

popular.

King George I, half the members of Parliament, Sir Isaac Newton,

the poet Alexander Pope, and countless merchants and tradesmen had

speculated on the South Sea and other companies.

They all were sucked in by a perfect magnetic storm: the rapid

advent of newspapers, ready loans at low interest rates, and

exciting narratives about technological innovation. Above all was

the eternal human desire to be part of the in crowd, or what we

today would call FOMO, fear of missing out. "Our species is really

a herd animal," says Andrew Odlyzko, a mathematician at the

University of Minnesota who researches financial bubbles.

Bubbles are as old as financial markets. Even in ancient

Babylon, commodity prices took sudden leaps and falls that can't be

fully explained by weather or war.

In 1720, "the scent of money was in the air like the breath of

spring," as the historian John Carswell put it. That June alone, 88

startups, most of them publicly traded, were launched in London.

Many sought to raise GBP1,000,000 to GBP5,000,000 apiece (roughly

$190 million to $945 million in today's money), tapping into what

Daniel Defoe, author of "Robinson Crusoe," called " the general

projecting humor of the nation."

A London housekeeper reportedly racked up GBP8,000 in gains, at

least $1.5 million in today's money. Fistfights broke out over the

right to buy stock while it still could be had; speculators

thronged London's financial district to buy shares in any company,

desperately pleading, " we don't care what it is."

Financial bubbles are often cited as proof of irrationality, but

what they prove is that investors are human. As one formerly

cautious banker, throwing some of his own money into the South Sea,

pointed out on June 18, 1720: "When the rest of the world is mad we

must imitate them in some measure."

New media technologies -- newspapers in 1720, radio in the

1920s, the internet in the 1990s, social media and smartphone apps

today -- are "the cultural substrate in which a mania can grow,"

says William Deringer, a financial historian at the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology.

As word spreads that "everybody" is doing something, it can be

hard for anybody to resist joining. Humans have a profound need to

belong to a group. Investing in something popular makes us feel

popular.

In 18th-century London, coffee houses and ballrooms became

centers of market gossip. One woman wrote: "South Sea is all the

talk and fashion. The ladies sell their jewels to buy, and happy

are they that are in... Never was such a time to get money as

now."

Two centuries later, the financial analyst Benjamin Graham wrote

about the bull market that ended in the crash of 1929: "Countless

people asked themselves, 'Why work for a living when a fortune can

be made in Wall Street without working?'" Graham added wryly, "The

ensuing migration from business into the financial district

resembled the famous gold rush to the Klondike, with the not

unimportant difference that there really was gold in the

Klondike."

Today, the online platform Reddit teems with speculators

boasting about their biggest trades.

Imitation isn't always irrational, either. It helped our

ancestors save mental and physical labor and adapt more quickly to

changing environments, says William Bernstein, a neurologist and

author of the forthcoming book "The Delusions of Crowds." Seeing

many others invest in something sends a powerful, if often

inaccurate, signal that it might be a good idea.

That can quickly coalesce into a narrative, in which our

imaginations rapidly transport us to different places and times.

("I'll become rich, just like they did.") A good story, as the poet

Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote, automatically triggers a " willing

suspension of disbelief for the moment."

The South Sea bubble brimmed with "story stocks." Among them

were firms claiming they would "trade in hair," import " a number

of large jack-asses from Spain," develop an " air pump for the

brain," convert sewage into gunpowder and even conduct an

unspecified business that would somehow "turn to the advantage" of

its investors.The South Sea Co. had its own story: Originally

created to sell enslaved people to Spain's American colonies, by

1720 it had morphed into a complex scheme for refinancing the

British government's massive war debts. Attracting investments from

the British public was key to making the scheme work -- or at least

appear to work. (In the end it failed, casting a pall over the

British economy for years to come.)

Investors today are barely wiser. Only last year, private funds

valued WeWork, the office-sharing company that claimed it would "

elevate the world's consciousness," at $47 billion. It was later

marked down by roughly 80%.

The South Sea bubble did have many critics at the time. But

conformity is a powerful force that can counteract gravity for

longer than skeptics often expect. Bubbles are neither rational nor

irrational; they are profoundly human, and they will always be with

us.

Write to Jason Zweig at intelligentinvestor@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 17, 2020 10:15 ET (14:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

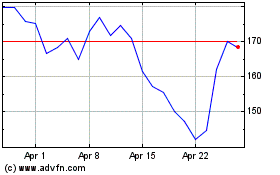

Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024