By Jing Yang

China's upstart Luckin Coffee Inc. grew at a blinding pace. It

opened stores faster than Starbucks Corp., doubled its valuation to

$12 billion eight months after going public and pleased its

big-name investors in the U.S.

Then, on April 2, Luckin said many of its sales had been

faked.

The shock brought a screeching stop to the three-year-old

juggernaut, sending its stock plunging 75% overnight. Since then,

investigators have delved into the books, executives have lost jobs

and a stock exchange has moved to delist Luckin, but no one has

explained just what went on inside the onetime corporate rocket

ship.

Now, some light can be shed.

It turns out that Luckin sold vouchers redeemable for tens of

millions of cups of coffee to companies that had ties to Luckin's

chairman and controlling shareholder, Charles Lu, according to

internal documents and public records reviewed by The Wall Street

Journal. Their purchases helped the company book sharply higher

revenue than its coffee shops produced.

Meanwhile, other internal documents showed a procurement

employee called Lynn Liang processing more than $140 million of

payments for raw materials such as juice, delivery and

human-resources services. Ms. Liang was fictitious, according to

people familiar with Luckin's business.

The scale and audacity of deception, which the Journal found

traced back to before Luckin's initial public offering on the

Nasdaq Stock Market just a year ago, has stunned international

investors and confounded regulators. This was a company that went

from founding to public listing in less than two years. Its sudden

fall saddled pension, mutual and hedge funds, not to mention

individual investors, with heavy losses both in Asia and the

West.

Luckin on May 11 ousted its chief executive, Jenny Qian, and

chief operating officer, Jian Liu, but provided little detail. It

suspended or put on leave six others.

Ms. Qian couldn't be reached for comment. Mr. Liu hung up when

reached by phone. The only one of the other six who provided a

comment said he was just following orders.

Mr. Lu didn't respond to questions from the Journal. On May 20,

he said in a public statement: "My style may have been too

aggressive and the company may have grown too fast, which has led

to many problems. But I by no means set out to deceive

investors."

He also apologized and restated his faith in the company in the

statement, issued after Nasdaq moved to delist Luckin's shares, a

decision Luckin said it would appeal.

Luckin said in response to questions from the Journal that a

committee of its board is continuing an internal investigation and

responding to inquiries from regulatory agencies in the U.S. and

China. It said it couldn't comment on specific details relating to

the probe at this time.

"The Company continues to take appropriate measures to improve

its internal controls and remains focused on growing the business

under the leadership of its Board and current senior management

team," Luckin said.

Nasdaq, although seeking to delist Luckin, last week permitted

its American Depositary Shares to resume trading after a six-week

suspension. They promptly resumed their drop. The shares closed

Wednesday at $2.59, versus a brief high above $50 in January.

Luckin's fall has rekindled long-running tensions over the U.S.

Securities and Exchange Commission's inability to inspect financial

records of Chinese firms to protect American investors.

The SEC is among the agencies investigating Luckin, according to

people familiar with the matter. In April it issued a renewed

warning about the risks of investing in companies in China and

other emerging markets. China's top business and commerce regulator

has raided Luckin's headquarters in Xiamen, China, and taken

records.

Luckin Coffee was born with a silver spoon in mid-2017, during

China's recent technology funding boom. While private it raised

more than half a billion dollars from investors including BlackRock

Inc., Singapore sovereign-wealth fund GIC and a bevy of Chinese and

American investment funds. Credit Suisse and Morgan Stanley courted

its executives and later won leading roles underwriting its public

offering.

Luckin's controlling shareholder, who goes by Lu Zhengyao in

addition to Charles Lu, is an entrepreneur who previously started

auto-rental firm CAR Inc. and a Chinese ride-hailing firm called

Ucar Inc.

Ms. Qian, an executive at those earlier ventures, co-founded

Luckin with Mr. Lu and became its CEO. They fashioned it as a tech

company that could disrupt the expanding business of coffee sales

in China, dominated by Starbucks.

Luckin built its strategy around a mobile app, with which it

sent vouchers for free coffee to tens of millions of people, and

coupons for deep discounts on later purchases. The discounts

brought the price of a latte down to 12 yuan, or $1.67, about a

third the cost of a similar drink at Starbucks.

Customers ordered and paid electronically, eliminating cashiers.

Luckin promised to deliver coffee within 30 minutes. It told

investors its model helped it collect data to optimize sales and

supply-chain efficiency.

By May 2018, just seven months after opening its first cafe,

Luckin had more than 500 of them, in over a dozen cities. It said

it obtained premium arabica coffee beans from Latin America and

Africa, syrup from Italy and milk from New Zealand. It boasted of

using high-end Swiss coffee machines and hiring award-winning

baristas to help design recipes and cafes.

At a glitzy launch party that included hordes of business

partners and journalists, Ms. Qian, standing in front of a giant

LED screen, said the goal was to provide affordable premium coffee

that people could access at any moment.

Days later, Luckin fired a salvo at Starbucks, which over two

decades had helped lure a tea-drinking population to coffee. Luckin

accused Starbucks of discouraging suppliers from doing business

with rivals and filed an antimonopoly lawsuit. Starbucks said it

welcomed competition. Luckin later dropped the suit.

A fundraising in June 2018 gave Luckin a billion-dollar

valuation just a year after its founding. The cash supercharged its

opening of cafes, many close to a Starbucks. The Seattle-based

giant, too, began delivering coffee to Chinese customers.

Luckin's IPO in May 2019 was a big success, raising $651 million

and valuing the company at around $5 billion on its first trading

day. Mr. Lu high-fived colleagues as the stock jumped.

Back in Xiamen, Luckin held a banquet for hundreds of business

partners, investors, bankers and lawyers. Guests posed for photos

at a booth mimicking the Nasdaq listing ceremony, and Ms. Qian

presented the next goal: 10,000 stores in China by the end of 2021.

Starbucks had fewer than 4,000 at the time.

"It was just explosive, humongous growth, and those numbers were

very seductive to a lot of investors," said John Zolidis, a

restaurant-industry analyst and president of Quo Vadis Capital,

which said it has never bought or sold Luckin stock.

A group of Luckin employees had already begun helping sales

along by engineering fake transactions, starting the month before

the IPO, according to people familiar with the operation. The

employees used individual accounts registered with cellphone

numbers to purchase vouchers for numerous cups of coffee. Between

200 million and 300 million yuan of sales ($28 million to $42

million) were fabricated in this manner, according to a person

familiar with the matter.

The undertaking became more complex. In late May 2019, orders

began flooding in under a fledgling line of business that involved

selling coffee vouchers in bulk to corporate customers, according

to internal records reviewed by the Journal.

Alongside bona fide voucher sales, to a few regular clients such

as airlines and banks, the records show numerous purchases by

dozens of little-known companies in cities across China. These

companies repeatedly bought bundles of vouchers, often in large

amounts. Rafts of orders sometimes came in during overnight

hours.

Qingdao Zhixuan Business Consulting Co. Ltd., situated in

China's northern Shandong province, bought 960,000 yuan ($134,000)

worth of Luckin vouchers in a single order, according to the

documents. They show it made more than a hundred similar purchases

from May to November of 2019.

Mainland China and Hong Kong corporate-registry records link

this company to a relative of Mr. Lu, to an executive of Mr. Lu's

previously founded Ucar Inc. and to a Luckin executive, via a

complex web of other companies and their directors and

shareholders. Qingdao Zhixuan also has the same telephone number as

a branch of CAR Inc. and is registered with a Ucar email

address.

Luckin booked more than 1.5 billion yuan ($210 million) of

corporate sales in this manner in 2019, dwarfing genuine purchases

during the period, according to a Journal analysis of the

records.

As money flowed in from the bulk sales, Luckin also made

payments to more than a dozen companies listed in its records as

providers of raw materials, delivery or human-resources services.

Many didn't exist until April and May of 2019, corporate

registration records show.

Chinese regulators who recently went through Luckin's systems

found more than 1 billion yuan (about $140 million) in questionable

supplier payments, according to the company's internal documents

and people familiar with the matter. The documents showed payments

were processed by Ms. Liang, the woman described as fictitious by

people familiar with Luckin.

According to internal records and a person familiar with the

matter, Luckin CEO Ms. Qian approved the payments and, in some

instances, actively saw to the progress of the payment processes.

The payments bypassed the chief financial officer, who then didn't

oversee Luckin's finance and treasury department, the person said.

The CFO, Reinout Schakel, declined to comment.

A look at registration records of companies that bought vouchers

and others that received repeated supplier payments shows that many

had links to Luckin, Mr. Lu or Mr. Lu's two previous ventures. Some

listed the same office addresses and contact numbers as branches of

CAR Inc. or Ucar. Several were registered with email addresses of

employees of those companies. One was registered with a Luckin

email address.

A few of the companies had links to a relative or a friend of

Mr. Lu. One regular bulk buyer of coffee vouchers, Date Yingfei

(Beijing) Data Technology Development Co. Ltd., has the same phone

number as a branch of CAR Inc. and a predecessor of Ucar.

Zhengzhe International Trade (Xiamen) Co. shows up in the

documents as a supplier of raw materials to Luckin.

Date Yingfei and Zhengzhe have the same legal representative,

Wang Baiyin, a former classmate of Mr. Lu. Mr. Wang owns 60% of

Date and 95% of Zhengzhe, according to corporate registration

records. Mr. Wang couldn't be reached for comment.

Not all details of the operations could be learned. People

familiar with these transactions surmised that, over time, the

rafts of purchases and payments formed a loop of transactions that

allowed the company to inflate sales and expenses with a relatively

small amount of capital that circulated in and out of the company's

accounts. It remains unclear what was the original source of funds

to kick-start the transactions.

In November 2019, Luckin reported a 558% year-over-year jump in

third-quarter product sales, and projected around a 400% rise for

the fourth quarter. Average net revenue from products per store

soared 80%, its financial report showed.

About two months later, after the stock price had roughly

doubled, Luckin raised $865 million in a follow-on sale of shares

and convertible notes. Its stock climbed further when Luckin said

it had overtaken Starbucks by number of cafes in China and it would

roll out numerous vending machines selling its drinks.

Then, on Jan. 31, Muddy Waters LLC, a U.S. short seller with a

record of exposing misbehavior at Chinese companies, circulated an

89-page unattributed report on Luckin. The report said an

examination of more than 11,000 hours of video footage of customer

comings and goings, of more than 25,000 customer receipts and of

observation by 1,500 individuals who visited Luckin outlets showed

that much of the company's revenue must be fabricated.

Luckin's stock took a dive but started rising again after the

company denied the allegations. The report was released around the

time Luckin's auditor was set to review 2019 results.

Two months later, on April 2, came Luckin's explosive

disclosure. Luckin said that as much as 2.2 billion yuan (about

$310 million) of its 2019 revenue had been fabricated. That

represented nearly half of its reported and projected sales from

April to December.

Auditor Ernst & Young Hua Ming LLP indicated the following

day it had sparked an internal investigation by finding that some

management personnel at Luckin fabricated transactions leading to

inflation of income, costs and expenses.

Luckin's once $12 billion valuation is now around $650

million.

"Luckin Coffee has been mired in an unprecedented crisis and a

maelstrom of public debates," an internal company memo said on May

12. "We believe, with the help of all Luckin staff, the company

will overcome the crisis and get back on track."

--

Zhou Wei

contributed to this article.

Write to Jing Yang at Jing.Yang@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 28, 2020 12:24 ET (16:24 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

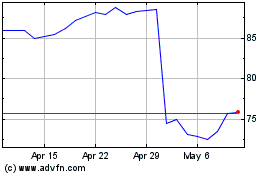

Starbucks (NASDAQ:SBUX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

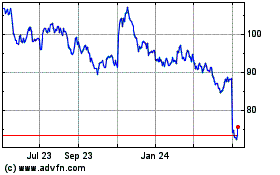

Starbucks (NASDAQ:SBUX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024