By Amber Burton,Justin Scheck andJohn West

A half-century ago, the federal government set out to attack the

racial wealth gap by supporting Black-owned banks. Policy makers

hoped the banks would lend to Black communities sidelined by the

mainstream financial system.

But five decades of federal financial and regulatory support

have failed to boost America's Black-owned banks. The majority have

disappeared under the burden of soured loans, bigger competitors

created by mergers and financial downturns that hit small lenders

hard. Fifteen years ago America had 36 Black-owned banks,

government data show. Now there are 18.

And Black people still face obstacles to getting loans. Would-be

borrowers in Black neighborhoods over the past decade have been

less likely to have their home loans approved than borrowers in

other neighborhoods, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of

federal data in the nine largest cities by raw Black

population.

Those who do get home loans are likely to pay more than other

borrowers on comparable loans. A FDIC survey found last year that

13.8% of Black households in America don't have bank accounts at

all, compared with 5.4% of the overall population. The survey also

found that 72.5% of all U.S. households used bank credit last year,

but just 52.5% of Black households.

Now a new generation of entrepreneurs, companies and regulators

is trying a different strategy. They are promising to strengthen

Black-owned banks by building up their capital with private

investments and giving them new ways to earn money with hundreds of

millions in big corporate deposits. Their hope is that this

approach will ultimately improve Black communities' access to

capital.

Federal authorities define Black-owned banks as lending

institutions regulated by the U.S. government that have more than

51% of the voting stock in the hands of Black owners. Such lenders

flourished during the early part of the 20th century as a key

source of capital for Black borrowers. The Nixon administration

offered support in 1969, leading to direct government deposits from

the U.S. Treasury. The approach was part of what Mr. Nixon called

in an executive order an attempt to "obtain social and economic

justice" for minorities. In 1989 Congress ordered regulators to

provide additional forms of technical support to Black-owned banks

and other minority-run financial institutions.

Black-owned banks have succeeded in making capital more widely

available in the sense that they approve a higher percentage of

Black applicants' loans than other banks. But their impact on the

communities they serve is increasingly limited by their small size

and often precarious financial standing.

The reasons are both specific and systemic. Black-owned banks

often believe they can do a better job assessing the risk of Black

borrowers, but they tend to make riskier loans due to their

deliberate lending to consumers shut out by mainstream banks. They

also share many of the same problems afflicting small community

banks: a limited number of branches, little money to invest in the

type of mobile-banking technology that might attract new customers

and an industry consolidation that increasingly puts more market

share in the hands of megabanks like JPMorgan Chase & Co. and

Bank of America Corp. The total number of banks insured or

supervised by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation has

declined by 45% since 2001, compared with a drop of 56% for the

number of Black-owned banks over the same period.

As consolidation made big banks even bigger, it has become

increasingly hard for small banks -- Black and otherwise -- to

compete. That consolidation hasn't been a fix to the problems that

Black banks were supposed to solve. A FDIC survey last year found

Black households were about five and a half times more likely to be

unbanked than white households, a slight improvement from a decade

earlier.

The limitations of Black-owned banks intensified in the

aftermath of the 2008-09 financial crisis, which was triggered by a

housing bust. In Chicago, Milwaukee and New Orleans, four

Black-owned banks that eventually failed were more likely to

approve Black borrowers' home-loan applications than banks were

overall during a period between 2007 and 2014, according to a Wall

Street Journal analysis of federal home-lending data. But these

banks never got big enough to significantly improve access to

mortgages in their neighborhoods. None received more than 1.3% of

all loan applications from Black borrowers in the Census tracts in

which they were active during a period starting in 2007 and ending

with their closures.

One of the banks that went under was Covenant Bank, which served

a largely poor and Black community on Chicago's West Side. "We were

trying to eradicate poverty," said its former chairman, the Rev.

Bill Winston. "That was our endgame."

When regulators ordered the Chicago bank to raise capital to

cover loans that went sour after the 2008-09 financial crisis, Mr.

Winston said he couldn't attract outside support and burned through

more than $2 million of his own money. The bank failed in 2013.

"The little guys don't have a shot," Mr. Winston said.

A New Push

Some big companies are trying to change the lopsided odds for

Black-owned banks by becoming customers of the banks themselves.

Their interest intensified after the May killing of George Floyd

while in police custody. Both Netflix Inc. and PayPal Holdings Inc.

said they would provide deposits to existing Black-owned banks,

giving them a bigger financial cushion and more money to lend.

Due in part to this new push, assets at Black-owned banks rose

about 10% in the second quarter of 2020 from the first. It was the

biggest quarter-to-quarter change in two decades.

Corporate deposits are a stable, low-cost source of funding for

banks. The more of these prized customers banks have, the greater

capacity they have to lend. Netflix has committed $100 million to

the effort, including $25 million to a community development

nonprofit that will help deploy the funds via loans and deposits in

Black-owned banks.

PayPal recently deposited $50 million in Black-owned Optus Bank

in Columbia, S.C. as part of a $350 million push to support Black

businesses, and Bank of America also bought a stake in the same

lender. Optus Bank almost doubled its assets in the past year

alone, to $155 million as of the end of June.

Assets aren't the only measure on the rise at Optus. Total net

income was $2.8 million in the third quarter, up from $366,000 in

the same year-ago period.

"Our goal is to have an impact on the financial health, access

and generational wealth creation for underrepresented minorities,"

a PayPal spokeswoman said.

Dominik Mjartan, Optus's president, said the PayPal deposit

allowed it to fund $40.5 million in loans through the Paycheck

Protection Program, the federal government's coronavirus lifeline

for small businesses. Some of the businesses -- including an

auto-repair shop that had to shut down earlier in the pandemic --

would have closed for good without the funding, he said.

"You cannot solve 400 years of disparity with a deposit," he

said. "But it can create movement."

Mr. Mjartan said Optus Bank is focused on serving people who

don't fit the stereotypical mold of a borrower at mainstream banks.

He recognizes that some of his customers' property value might be

slower to recover after a recession or their credit scores might be

lower due to systematic inequality, but said his bankers take the

time to look beyond what's on paper.

"On paper would a traditional bank say they are more risky?

Probably," he said. "But would we say that? No. For us their

stories are more complicated. Their stories require our lenders to

spend more time and really understand the unique circumstances of

each person and then offer a solution that maximizes the chances of

their success."

There are other initiatives under way to support more of these

Black-owned institutions. One is from Ashley Bell, an Atlanta

lawyer and former regional administrator for the Small Business

Administration during the Trump administration. He is putting

together a nonprofit that intends to raise $250 million to buy

stocks in Black-owned banks, via an entity called the Black Bank

Fund. The initiative is being led by Dentons, the law firm where

Mr. Bell works, and consulting firm KPMG, and aims to buy nonvoting

shares in Black banks.

The idea, Mr. Bell said, is to leave decision making power in

the hands of the banks' Black owners while providing extra capital

so the banks can significantly increase the amount of money they

can loan. Mr. Bell said he is hoping the effort will help

Black-owned banks increase their income as well as their services.

Most such banks, for example, currently don't have

wealth-management arms. "How can you create intergenerational

wealth if you don't even offer that service in your community?" he

said.

A new financial-services company in Atlanta is trying to bring

new customers to Black banks partly through the prominence of its

co-founders: former Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young and hip-hop artist

and activist Michael Render, known as Killer Mike. Their company,

Greenwood, will issue debit cards and offer online deposit services

via accounts at other banks.

The recent history of Black banks can leave a person with a "sad

and hopeless feeling," said Mr. Render, who started a #BankBlack

campaign in 2016. Many Black people, he said, have felt

marginalized by the mainstream financial system. "We've never been

allowed to fully participate," he said. He argues there is

widespread demand in the Black community for better financial

services. "Black people have understood capitalism, at their core,

since they were the capital," he said.

Rather than funnel capital into existing banks, Mr. Render said

he wanted to start a business that would close some of the gaps

between Black banks and their bigger competitors, starting with

technology. Greenwood is planning to offer mobile-banking apps that

will let users access accounts at small Black-owned banks as easily

as they could access accounts at big mainstream lenders, taking

away an obstacle to opening accounts at small banks.

Mr. Render said he is modeling the idea on the Greenwood

neighborhood of Tulsa, Okla., a thriving Black business district

that was razed by white mobs in 1921. Mr. Render said he was taken

with the idea that Greenwood brought wealth to Tulsa's Black

community in part by connecting it to the larger economy. He and

Greenwood President Aparicio Giddins said Greenwood will offer

accounts with Black-owned banks and mainstream banks, in part to

link Black customers with the mainstream, and in part, Mr. Render

said, because he is concerned that the 18 remaining Black-owned

banks have limited capacity to take on large numbers of new

customers.

A Black Banking Boom

The idea of lending specifically to Black Americans began with

Reverend William Washington Browne, an ex-slave who started a

fraternal organization to support Black enterprises and founded

America's first Black-owned bank in Richmond, Va in 1888. By 1900,

the Savings Bank of the Grand Fountain United Order of True

Reformers had branches in 24 states. Regulators closed the bank 10

years later.

Black-owned banks boomed from 1910 to 1930, said Mehrsa

Baradaran, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine,

who researches Black banks. Citizens Trust Bank, located in

Atlanta, and Industrial Bank, based in Washington, D.C., were two

that resulted from this early burst.

In that segregated era, they were often the only banks that

would lend to people in Black neighborhoods. For decades,

mainstream lenders shut out minority communities through

"redlining" -- the now illegal practice of refusing mortgages for

people in low-income and Black neighborhoods.

An entrepreneurial spirit born out of exclusion reverberated

into the 1960s, Ms. Baradaran said. The Civil Rights era produced

another boom of interest in Black banks, from activists and the

government. Though Congress in 1968 had just outlawed "redlining,"

officials remained concerned that discrimination would continue. If

mainstream banks wouldn't lend to minorities, the thinking went,

then perhaps minority-owned lenders would help bring financial

equality.

In 1969, the Treasury Department began depositing money in

Black-owned banks to boost their capital so they could lend to

communities that mainstream banks continued to shun. The Minority

Bank Depository Program still encourages government agencies to

deposit funds in minority and women-owned banks. As of 2020 there

were 71 minority banks enrolled in the program and the total amount

of deposits collected by the banks in fiscal year 2020 was $32.6

million.

In 1989, Congress passed more legislation that tasked the FDIC

with providing technical support and advice to minority-owned

depository institutions so they could continue to support

underserved communities.

The Nixon-era policy of supporting Black-owned banks as a way of

addressing lending inequities had a flaw, said Anne Price, the

president of advocacy group Insight Center for Community Economic

Development. Several dozen little banks couldn't possibly cancel

out entrenched discrimination by the country's biggest lenders.

Relying on Black-owned banks to solve the problem inadvertently

absolved everyone else, she said.

"In a way, there were two markets set up: one for Blacks and

another for whites," she said.

Black-owned banks now account for just 0.2% of all banks

regulated by the FDIC, according to June 30 data. The last

Black-owned bank to go under was City National Bank of New Jersey,

which regulators seized in November 2019. Total assets at America's

Black-owned banks were $4.5 billion as of June 30, according to the

FDIC, down from $4.7 billion in 2005.

The largest Black-led bank -- a planned union of Los Angeles's

Broadway Federal Bank and Washington, D.C.'s City First Bank --

will have $1 billion in assets if that merger closes in 2021.

The FDIC's inspector general said in a 2019 report the FDIC

achieved its goals by preserving and promoting minority banks and

ensuring they remained minority led or owned. An FDIC spokeswoman

in an interview said assets controlled by Black-owned banks haven't

dipped since 2001 despite the fact there were twice as many of

these banks then as in 2019.

At the same time, according to the inspector general's report,

the technical support provided by the FDIC didn't seem to help

minority banks stay open. The inspector general also cited a study

from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago showing that Black-owned

banks faced bigger challenges, like maintaining enough capital, to

stay in business from 2011 to 2017 than other minority-owned

banks.

The FDIC is now seeking new ways to help the remaining

Black-owned banks stay healthy, a spokesman said. It is starting a

fund run by an independent manager will assist companies that want

to invest in minority institutions but may not know how. And

minority institutions will be able to request support in the form

of equity, help with troubled assets, or other investments. "This

is by no means a panacea, but it's an important leap forward," he

said.

'Just Let It Rot'

The problems of Black-owned institutions accelerated in the

aftermath of the 2008-09 crisis, when their numbers contracted by

42% over 12 years -- slightly more than the 38% drop for all banks

supervised by the FDIC. In Milwaukee, the Black-owned Legacy Bank

found itself burdened with troubled loans that were mostly caused

by the economic downturn. Margaret Henningsen, one of the bank's

founders, was trying to raise additional capital in 2011 when

regulators decided the bank was no longer viable. It was acquired

by another Black-owned lender, Seaway Bank & Trust Company.

Seaway itself failed in 2017.

"It broke my heart," said Ms. Henningsen, "After watching Seaway

take on other troubled banks, it became a troubled bank."

Eighty-one miles south in Chicago, the crisis made life

considerably more difficult for another Black-owned bank called

Covenant. Its chairman, Mr. Winston, wanted to eradicate poverty

and borrowed from a Black-owned bank in 1997 to buy an abandoned

mall to house his congregation when mainstream banks wouldn't lend

to him. A decade later, he and his parishioners pooled their funds

to buy a bank of their own.

It began with optimism. With funding from his personal accounts

and his parishioners, Mr. Winston's group acquired the tiny

Community Bank of Lawndale, which had a single branch in a

predominantly Black neighborhood. He came up with a plan to put a

new branch in the mall his church bought -- making it a convenient

place for congregants to do business.

Over five years, Covenant extended more than $19 million in

loans to a largely Black clientele. Bank employees also went to

local churches to teach congregants the basics of finance.

Then the bank got caught in a downward spiral during the 2008-09

crisis as its customers struggled. Covenant would grant borrowers

who couldn't pay extensions on their loans. These loans had to be

downgraded on the bank's books, forcing the bank to raise more

capital.

"The minority community is usually the first laid off," Mr.

Winston said. "They can't pay on the loans they have."

Mr. Winston tried to sell additional shares in Covenant, but

potential investors balked. He said he approached bigger banks and

companies in the area to see if they would deposit money with

Covenant, but didn't get any traction. So he put more of his own

money in -- more than $2 million in the end -- to keep Covenant

afloat.

Regulators shut down Covenant in 2013 and sold its assets to

another Black-owned lender. Mr. Winston said he is still angry that

some local media coverage blamed him for pushing congregants into a

bad investment. He said he felt he was being criticized for trying

to fix a system that he believes is stacked against Black borrowers

and Black banks alike.

"I got wiped out," he said. "I just got weary. I just couldn't

hold it anymore. One of the board members said to me: 'Pastor,

don't put in any more money. Just let it rot.'"

Searching for the Middle Class

In many ways, the struggles of Black-owned banks and small,

community lenders are one and the same. Thousands of small banks

have closed their doors over the last three decades, while the

biggest banks have continued to grow.

America's biggest banks spend tens of billions of dollars a year

on technology. They offer a full range of financial services --

credit cards, retirement planning, deal-making advice -- that

wealthy consumers and big businesses want and need. When those

customers leave, tiny banks are left with lots of tiny

accounts.

"What really would help us is if potential customers would look

at our residential and commercial loan products," said B. Doyle

Mitchell Jr., the president and CEO of Black-owned Industrial Bank

in Washington, D.C.

Industrial has been in Mr. Mitchell's family for three

generations, and was strong enough last year to acquire the closed

City National Bank of New Jersey. In June, Industrial got a $5

million grant from Morgan Stanley.

But to thrive, Mr. Mitchell said, Industrial and America's

remaining Black-owned banks need something else: more middle-class

borrowers. Small accounts carry the same expense as larger

accounts, he said.

Small banks make money on the spread between what they pay

depositors and what they charge borrowers. For banks to make a

profit, the good loans must far outnumber the bad. Black-owned

banks that cater to riskier borrowers often find themselves on the

wrong side of the equation.

Mr. Mitchell also knows that the bank will need to capture the

attention of younger Black borrowers who could essentially take

their credit anywhere.

"We have focused on appealing to millennials and young

entrepreneurs over the last five years with social media campaigns

and new products," said Mr. Mitchell. The bank is about to launch a

new automated digital platform speeding up the process of approval

of home loans and allows clients to apply online. "We're making the

investments," he said.

The bank has found help from the government and one of the

nation's largest banks. In 2018, Citigroup Inc. became a mentor to

Industrial Bank through the U.S. Department of the Treasury's

Financial Agent Mentor-Protégé Program. Industrial was the first to

do work with the Department of Treasury through the program. It is

a subcontractor to Citigroup, and Citigroup is serving as a mentor

helping the bank learn how to manage risk and diversify its

portfolio with more predictable and long term opportunities.

"It's a long learning curve," said Mr. Mitchell. "But it's

slowly beginning to bear fruit."

For Citigroup, the partnership is part of its larger initiative

to mentor and lend support to minority depository institutions. It

now has six banks that it mentors.

"Anyone can give money, what we're doing are things that will

make a sustainable long term impact," said Harold Butler, who leads

the program at Citigroup.

Write to Justin Scheck at justin.scheck@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 16, 2020 13:49 ET (18:49 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

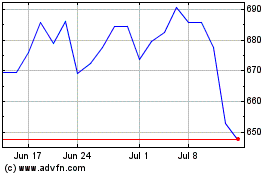

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024