By Marc Randolph

"Jesus, Reed, where are you taking us?"

The street we were walking on looked like a movie set of skid

row. There was trash on the sidewalk, broken glass in the window

casements.

"Should be right around the corner," Reed replied, squinting

down at the Seattle map he'd printed out that morning.

I glanced toward a group of shabbily dressed young men huddled

in the doorway of a large building. "Somehow I think I expected

something a little more...I don't know, modern?"

"There it is," Reed said, pointing to a rundown four-story brick

building. He seemed less certain now. Leaning in toward one of the

tall windows, I could just see into the dimly lit lobby. On the

wall, behind a faded wood desk, was a large sign reading

Amazon.com.

It was the summer of 1998. DVDs had been in the U.S. market for

a little over a year, and Netflix, the e-commerce company Reed

Hastings and I had co-founded to sell and rent them through the

mail, had been live for just over two months. I was the company's

CEO, Reed its largest investor.

Netflix was still pretty small, but we had big dreams: We saw

ourselves as an alternative to Blockbuster and Hollywood Video. The

bad news was that we weren't making much money. And what little

money we were making was coming almost entirely from DVD sales, not

rentals. I feared that once others started selling DVDs, our

margins would shrink to nothing.

So when Joy Covey, Amazon's chief financial officer, called Reed

to see if we would be interested in coming up to Seattle to meet

with her and Jeff Bezos, Amazon's founder and CEO, I felt a mixture

of both fear and hope.

Amazon was only a few years old, but Bezos had already decided

his site wouldn't just be a bookstore. It was going to be an

everything store. And we knew that music and video were going to be

his next two targets.

We'd also heard that Bezos planned to use a good chunk of the

$54 million raised during his company's 1997 IPO to finance an

aggressive acquisition of smaller companies.

It didn't take us long to figure out why Jeff and Joy wanted to

meet. Netflix was in play.

That feeling -- although thrilling -- was also a little

bittersweet. I wasn't quite ready to hand over the keys. But when

Amazon calls, you pick up the phone. Even if it's 1998, and Amazon

is nowhere near the powerhouse it is today.

The building Reed and I entered certainly didn't look like it

belonged to a powerhouse. The reception area was cluttered and

dusty. On the desk was a telephone with a printed directory of

numbers. Reed leaned over, squinted and dialed.

Within seconds, Joy swept into the lobby. She was younger than

either of us. But she was already a respected businesswoman, a

dynamo who had taken Amazon public just 12 months earlier,

convincing skeptical investment bankers that a company that wasn't

remotely profitable was worth $20 billion.

As Covey led us back into the warren of cubicles that made up

the Amazon offices, it was hard for me to believe that this was the

company inventing e-commerce. The carpeting was stained. There were

multiple people per cubicle, desks under the stairs, desks pushed

to the edges of hallways. Almost every horizontal surface was

covered: by books, gaping Amazon boxes, printouts, coffee cups,

plates and pizza boxes. It made the Netflix offices seem like the

executive suite at IBM.

We could hear Jeff Bezos before we saw him. He-huh-huh-huh-huh.

Jeff has a...distinctive laugh. If you've seen any video of him

speaking, you'll have heard a version of it -- but not the true,

untamed thing. Now it's polite, a little giggly. But back then, it

was explosive, loud, hiccupping. He laughed the way that Barney

Rubble laughs on "The Flintstones."

He was in his office, just hanging up the phone when we walked

in. His desk, and the desks of the two other people he shared the

office with, were made of doors mounted atop 4 × 4 wooden legs,

braced with triangular metal pieces. I suddenly realized that every

desk I'd seen in that office was the same.

Bezos was wearing pressed khaki pants and a crisp blue oxford

shirt. Behind him, hanging from an exposed pipe in the ceiling,

four or five identical pressed blue oxford shirts fluttered in the

breeze from an oscillating fan.

After introductions, we filed into a corner of the building with

a bigger table. This table, too, was made from recycled doors. I

could clearly see where the holes that used to hold the doorknobs

had been patched.

"OK, Jeff," I said, grinning. "What's with all the doors?"

"It's a deliberate message," he explained. "It's a way of saying

that we spend money on things that affect our customers, not on

things that don't."

Netflix was the same way, I told him. We didn't even provide

chairs.

Bezos was notoriously frugal. He was famous for his "two-pizza

meetings" -- the idea being that if it took more than two pizzas to

feed a group of people working on a problem, then you had hired too

many people. People worked long hours for him, and they didn't get

paid a lot.

But Bezos inspired loyalty. He's one of those geniuses -- like

Steve Jobs, or like Reed -- whose peculiarities only add to his

legend. In Jeff's case, his legendary intelligence and notorious

nerdiness mix into a kind of contagious enthusiasm.

He peppered me with questions about Netflix. How could I know

that I had every DVD? What did I expect the ratio of sales to

rentals to be? But he was most excited about the stories about

launch day -- particularly, the story of the bell we had rigged up

to mark each new order.

"We had the exact same thing!" he exclaimed. "A bell that rang

every time an order came in. I had to stop everyone from rushing

over to the computer screens to see if they knew the

customers."

We traded beta names: he laughed at Kibble, the name we had used

before Netflix's launch, and told me that Amazon had originally

called itself Cadabra. "The problem is that Cadabra sounds a little

too much like cadaver," Bezos said, barking out a laugh.

Although Amazon was still relatively small in 1998, it already

had over 600 employees and was doing more than $150 million in

revenue. But as Jeff and I chatted about our launch days, I could

see in his face that in many ways he missed those simpler, more

exciting times.

Reed, on the other hand, has never been someone who dwells, at

all, on the past. He was impatiently jogging his leg up and down.

He wanted, I knew, to direct the conversation to how Netflix could

potentially fit with what Amazon was doing.

I was just about to brief Jeff and Joy on key members of our

team, when Reed decided he'd had enough.

"We don't need to go through all this," he said, exasperated.

"What does this have to do with Netflix and Amazon and possible

ways we can work together?"

Everyone stopped. It was quiet.

"Reed," I said after a few seconds. "It's obvious that Amazon is

considering using Netflix to jump-start their entry into video. Our

people would be a huge part of any possible acquisition."

I was relieved when Joy jumped in to help. "Reed," she said,

"can you help me understand a bit better how you're thinking about

your unit economics?"

With obvious relief that we were finally on topic, Reed began

running Joy through the numbers.

An hour later, after Bezos had headed back to his office, Joy

lingered behind to wrap things up. "I'm very impressed with what

you've accomplished," she started, "and I think there is lots of

potential for a strong partnership to jump-start our entry into

video. But..."

I'm not a "but" man. Nothing good ever comes of that word. This

time was no exception.

"But," Joy continued, "if we elect to continue down this path,

we're probably going to land somewhere in the low eight

figures."

When someone uses "low eight figures," that means barely eight

figures. That means probably something between $14 million and $16

million.

That would have been a pretty good outcome for me, since at the

time, I owned about 30% of the company. Thirty percent of $15

million is a pretty nice return for 12 months of work --

particularly when your wife is broadly hinting that it might be

time to pull the kids out of private school, sell the house, and

move to Montana.

But for Reed, it wasn't enough. He owned the other 70% of the

company, but he'd also invested $2 million in it. And he was fresh

off the sale of Pure Atria, the company formed out of his first

software venture. He was already an "eight-figure guy." A

high-eight-figure guy.

On the plane ride home, we discussed the pros and cons. The

pros? We'd find a solution for our biggest problems: We weren't

making any money. We didn't have a repeatable, scalable or

profitable business model. We were doing plenty of business, most

of it through DVD sales, but our costs were high. It was expensive

to buy DVDs, to ship them and to give away thousands of them in

promotions, hoping that we'd convert one-time users into return

customers.

And of course there was the bigger problem: If we didn't sell to

Amazon, we would soon be competing with it. So long, DVD sales. So

long, Netflix.

Selling now would solve all those problems -- or at least it

would hand them off to a larger company with deeper pockets.

But...

We were also on the brink of something. We had a working

website. We had a smart team. We had deals in place with a handful

of DVD manufacturers. We had figured out how to source virtually

every DVD currently available. We were unquestionably the best

source on the internet for DVDs.

It didn't seem like the right moment to give up.

"Listen, Marc," Reed said as we watched Mount Rainier scroll by

outside the window. "This business has real potential. I think we

could make more on this than on the Pure Atria deal."

I nodded in agreement. Then I chose that moment to tell Reed we

should abandon the only profitable part of our business.

"We just have to figure out some way to get out of selling

DVDs," I said to him. "Doing rental and sales is confusing for our

customers and unnecessarily complex for ops. And if we don't sell,

Amazon will destroy us when they enter the field. I think we get

out now. Focus on rental."

Reed arched his eyebrows.

"Kinda puts all our eggs in one basket," he said.

"That's the only way to make sure you don't break any," I

replied.

One of the key lessons I learned at Netflix was the necessity of

focus. At a startup, it's hard enough to get a single thing right,

much less a whole bunch of things. Especially if the things you are

trying to do are not only dissimilar but actively impede each

other.

Reed agreed with me. "You're right," he said. "If we get funding

this summer, that'll buy us some time. It's a difficult

problem."

He frowned, but I could tell he was pleased to have something

new to chew on.

"What percentage of revenue comes from rental right now?"

"Roughly 3%," I said, signaling to the flight attendant for a

much-needed gin and tonic.

"That's horrible," Reed said. "But sales are a Band-Aid. If we

rip it off..."

"Then we have to focus on the wound," I said, squeezing my lime

into the drink.

We went back and forth like this for the rest of the plane ride,

and it was only when we landed that I realized we hadn't actually

formally decided not to take Bezos's offer. Without deciding, we'd

decided: We weren't ready to sell.

We agreed that Reed would let Amazon down lightly -- and

politely. In the future, we'd be better off having Amazon as a

friend, not an enemy.

In the meantime, we needed to figure out a way to get people

renting from us.

Adapted from "That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the

Amazing Life of an Idea" by Marc Randolph, the co-founder and first

CEO of Netflix. Copyright (c) 2019 by Marc Randolph.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 06, 2019 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

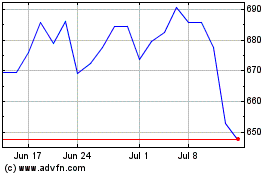

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024