By Newley Purnell

NEW DELHI -- After Walmart Inc. sealed a $16 billion deal last

year to buy India's biggest domestic e-commerce startup, it got

some bad news. India was changing its e-commerce regulations.

Foreign-owned online retailers would need to modify their supply

chains and stop deep discounting. Those rules didn't apply to

Indian companies.

India, the world's biggest untapped digital market, has suddenly

become a much tougher slog for American and other international

players.

Over the past year, Indian policy makers have begun erecting

roadblocks through special requirements for how U.S. tech companies

structure their operations and handle data collected from Indian

customers, according to industry executives and experts following

the market.

Seeking to match China's success at protecting and promoting

homegrown tech giants, such as Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., Tencent

Holdings Ltd. and TikTok parent Bytedance Inc., India is

increasingly trying to shelter domestic companies. In the

crosshairs, beyond Walmart, are firms including Amazon.com Inc.,

Alphabet Inc.'s Google and Facebook Inc. and its WhatsApp messaging

service.

Indian officials say they have an array of aims: protect small

bricks-and-mortar businesses, secure user data and allow room for

India's own tech firms to grow. That smacks of protectionism to

Western tech executives, who say India's goals make it difficult to

predict business conditions.

India's moves come as populist sentiment rises globally and U.S.

technology titans come under scrutiny around the world for their

use of personal data and potentially anticompetitive tactics.

Europe, too, has been cracking down on U.S. tech firms, although

European Union officials say their efforts are driven more by

regulatory goals than by any desire to protect local companies.

Europe has few domestic tech titans.

India's new rules apply to Flipkart Group, the Bangalore-based

Amazon competitor that Walmart acquired to gain a foothold in

India's fast-growing e-commerce sector. They also affect Amazon,

which is plowing $5 billion into India to expand its own

operations.

In each sector where Indian bureaucrats are throwing up

challenges, Indian companies stand to benefit.

"I know there are some who look to the Chinese model with

admiration," said Nick Clegg, a former deputy prime minister of

Britain now serving as Facebook's vice president for global

affairs, in a talk at a New Delhi think tank in September. "They

see the success of Chinese internet companies like Alibaba and

TikTok and wonder if the same protectionist approach could reap

rewards for India, too." He called on India to reject that

model.

The Indian government's primary goal is to encourage economic

growth, said Gunjan Bagla, managing director of Malibu,

Calif.-based consulting firm Amritt Inc., which helps American

firms do business in India. Policy makers there are struggling to

get a handle on the rapid rate of "disruptive innovation by the

likes of WhatsApp and Uber," he said.

An Amazon spokeswoman said the company is working with Indian

policy makers and will "watch closely as the country's leadership

sets its course for the future." A Google spokesman said the

company thinks "governments across the world need to look at

striking the right balance to protect the interests of citizens and

promote innovation." Walmart declined to comment.

Indian policy makers have disputed that their actions aim to

hobble foreign companies. They say they want to nurture domestic

players and to protect data gathered in the country, which is why

they are pushing for servers to be located on Indian soil.

"I have been very clear: We will never compromise our data

sovereignty," said Ravi Shankar Prasad, India's communications,

electronics and information technology minister, at a government

conference in October.

A spokesman for Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata

Party denied the government was pursuing protectionist policies or

making it hard for U.S. tech companies to operate. He said the

government welcomes U.S. firms, but that they "cannot be allowed to

indulge in anticompetitive practices," referring to Amazon and

Walmart competing with India's mom-and-pop shops.

"Every country has data protection laws and regulatory

mechanisms," said the spokesman.

India represents the world's biggest market for what executives

refer to as the next billion users -- consumers who have never

searched or shopped online or made a digital payment.

There are 665 million internet users in India, according to the

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, meaning 685 million have yet

to get online. Forrester Research Inc. projects Indian e-commerce

sales to more than double to $68.4 billion by 2022, from $26.9

billion last year.

India has produced few startup unicorns -- firms valued at $1

billion or more -- that don't face competition from American

companies.

"One of the lessons they draw from China is that protectionism

can work, " said Julian Gewirtz, a Harvard University researcher

who studies China and has followed developments in India. "They see

these huge companies that go public and are built on protectionism

and state support. That is the most difficult argument to push back

against."

Indian tech entrepreneurs have a history of cloning American

companies and giving them a local twist. In 2007, two former Amazon

employees launched Flipkart, which quickly outpaced other Indian

e-commerce sites. Digital-payments company Paytm, launched in 2010,

allows consumers to use its app to pay for school fees and utility

bills, much like PayPal Holdings Inc. does. India's homegrown

version of Uber Technologies Inc., ride-hailing startup ANI

Technologies Pvt.'s Ola, launched in 2011.

Then the American titans began showing up. Amazon launched its

India website in 2013. Walmart's purchase of Flipkart came last

year. Now Amazon and Flipkart command more than 80% of all online

shopping sales, according to Morgan Stanley, leaving domestic

players as also-rans.

Uber launched in India in 2013 and has captured significant

market share from Ola. Ola co-founder Bhavish Aggarwal has accused

Uber of "capital dumping," or unfairly using its financial might to

underprice rides to gain market share. An Uber spokesman declined

to comment.

Google and Facebook, which have no sizable Indian rivals,

dominate digital advertising. Facebook's WhatsApp messaging service

has become India's default digital town square, used by family and

friends to chat and by businesses to keep in touch with customers.

It also has been used to spread rumors that have led to mob

violence, leading to condemnation by government officials.

When Prime Minister Modi was elected in 2014, he pledged to

improve India's image as a place to do business. He eased

foreign-direct-investment laws and replaced complicated taxes with

a nationwide levy on goods and services.

During his re-election campaign last year, government officials

began privately circulating draft policies on issues such as

e-commerce and rules requiring data to be stored within the

country.

Requiring local storage of data when computing is often done in

the cloud could force U.S. companies to use Indian data centers.

That might increase costs and raise the possibility that the Indian

government would seek access.

India's telecommunications regulator has been considering new

rules that could force WhatsApp to allow the government access to

messages on national-security grounds, or to trace messages that

spur violence. WhatsApp has a policy of protecting user privacy

with end-to-end encryption.

In February 2018, WhatsApp launched, for a limited number of

users, a digital-payment service that runs on an Indian government

platform that allows real-time money transfers. WhatsApp said at

the time it hoped to expand it to all users in India soon.

Nearly two years later, WhatsApp has yet to receive government

permission to do so -- a blow to Facebook's effort to wring revenue

from WhatsApp in India, its biggest market. New Delhi says that is

because WhatsApp's plan wouldn't comply with rules requiring all

payments data to be kept inside the country.

A WhatsApp spokesman said the company already has "localized the

required payments data and are awaiting government approval."

One beneficiary of the stalled rollout is Paytm, the Indian

digital-payments company.

Walmart had no warning that e-commerce regulations would change

after its acquisition of Bangalore-based Flipkart Group. It and

other U.S. e-commerce players sought clarifications after the Dec.

26 government announcement, according to people familiar with the

issue.

In January, an influential Hindu nationalist economic group

linked to Prime Minister Modi's party asked him in a letter to

resist any efforts by the American companies to push back against

or evade the law. In a separate letter, a group representing Indian

merchants threatened to initiate a nationwide boycott of Flipkart

and Amazon if the new regulations weren't enforced.

When Prime Minister Modi traveled to New York in September to

attend the United Nations General Assembly, he met with U.S. chief

executives and other business leaders and encouraged them to

continue to invest in India. When it came time for executives to

provide feedback, the first issue executives raised was data

localization rules, according to people familiar with the matter.

Prime Minister Modi's office didn't respond to requests for comment

about the meeting.

E-commerce executives met with Piyush Goyal, India's minister of

commerce and industry, in New Delhi in June. Amit Agarwal, who

heads Amazon's India operations, and Kalyan Krishnamurthy,

Flipkart's chief executive, told Mr. Goyal they were dissatisfied

with the tightening of e-commerce rules, according to people

familiar with the matter. Spokespeople for Amazon and Flipkart

declined to comment.

They told him they had invested heavily in India, educating

consumers about the benefits of online shopping and boosting the

sector for all firms. In effect, they said, they have created a

huge online-shopping market from scratch.

Mr. Goyal responded that India needs marketplaces -- open

platforms for buying and selling that can be used by India's

mom-and-pop shops -- not monolithic websites that act as single

markets, people familiar with the meeting said.

Mr. Goyal told reporters in October that Prime Minister Modi's

government "is clear about standing together with the country's

small retailers. We worry for them, and we won't let any harm to

come to them."

--Rajesh Roy contributed to this article.

Write to Newley Purnell at newley.purnell@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 03, 2019 10:39 ET (15:39 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

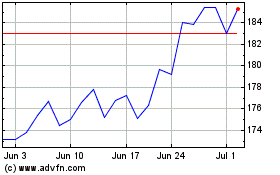

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

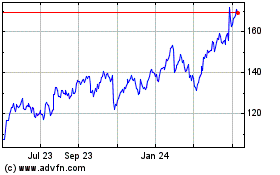

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024