By Christopher Mims

Is the mass advertising boycott hitting Facebook Inc. a

meaningful turning point for the social-media king? Or is it just

another public-relations storm it weathers on its way to joining

the Trillion-Dollar Club?

Companies like Coca-Cola and Unilever are pausing their

social-media spend, citing a variety of reasons, most commonly

their view that Facebook is not doing enough to eliminate hate

speech, and the way the company's products polarize and divide us

all. Sound familiar? Accusations like this are leveled at the

company with some regularity.

The boycott has brought a great deal of attention to the issue.

But it's not Facebook's first "we can do better" moment -- there

have been many, and there will probably be many more.

The concerns raised by advertisers, also including Starbucks and

Microsoft, can be answered with policy tweaks or public statements.

But they can probably never be fixed to the satisfaction of

everyone who feels invested in the behavior of Facebook because of

the nature of political discourse in America and beyond -- and

because of the nature of Facebook itself as a digital forum and a

business.

The content critics flag as unacceptable ranges from posts that

seem unambiguously hateful or maliciously dishonest to content a

significant share of the country might consider part of the

political conversation, even if they disagree with it.

The Anti-Defamation League, part of a coalition that pushed many

advertisers toward a boycott, compiled several examples of the type

of typically right-leaning hate speech and misinformation it says

is still often accompanied by ads from big-name brands. One was a

spoofed image of a woman in a head scarf on an Aunt Jemima-like

syrup bottle with the label "Aunt Jihadi." Another, on a conspiracy

group's page, claims the Federal Emergency Management Agency is

trying to start civil war "just like the days of Hitler," and

includes a photo of a military force rolling through an urban

street, captioned "MARTIAL LAW, FEMA Coffins In The USA."

But the current backlash owes in large part to Facebook's

handling of President Trump's posts on Twitter and Facebook saying

" When the looting starts, the shooting starts." Twitter flagged it

for "glorifying violence." Facebook left it alone, with Chief

Executive Mark Zuckerberg arguing that it's not Facebook's place to

regulate political speech -- a position that infuriated plenty of

his own employees.

In discussions of free speech, Facebook is sometimes likened to

a modern town square, but there's no precedent in history for it.

No town square could ever fit a third of the world's population,

let alone give a megaphone to each of those people.

And nothing of that size could ever be imagined to be governed

by one billionaire and his private army of bots and humans.

Facebook would like to depend on users and algorithms, but it is

increasingly dependent on thousands of low-paid contractors to

interpret its myriad guidelines about what constitutes permissible

content.

All of which helps explain why, to the question of who should

draw lines around what exactly is and isn't acceptable speech, Mr.

Zuckerberg has long favored the answer: "Not us."

After years of being frustrated by Facebook's perceived

inaction, a few groups of academics and civil-rights activists

began last November to discuss encouraging advertisers to boycott

Facebook, says Tristan Harris, president and co-founder of the

nonprofit Center for Humane Technology. He's been advising the

boycott movement, called " Stop Hate for Profit," which, in

addition to the ADL, includes the NAACP, Color of Change and

others.

Rashad Robinson, president of Color of Change, said that at a

June 1 meeting with Mr. Zuckerberg and Facebook Chief Operating

Officer Sheryl Sandberg, he became frustrated with the company's

inaction, specifically its failure to apply its hate-speech

policies to posts by President Trump, and its failure to bring in

an executive with civil-rights experience. "Toward the end of the

conversation I told Mark and Sheryl, 'What are we doing here, where

we ask for things, and you tell us you're doing things you're not

really doing?'"

Amid months of coronavirus-induced lockdowns and bleak economic

reports, the video of a Minneapolis police officer killing George

Floyd had gone viral and nationwide protests ensued. The ADL saw an

explosion of hate speech and conspiracy theories online, which

catalyzed the group and its partners to act, says its chief

executive Jonathan Greenblatt. Cue the boycott.

Some advertisers have said that pausing spending on Facebook is

solely about "brand safety," making sure their ads don't appear

with objectionable content. Verizon, for example, has clarified

that it is not joining the Stop Hate movement.

Others are riding the same cultural tidal wave that saw brands

posting on social media in support of the Black Lives Matter

movement. Coca-Cola issued a statement, citing racism on the

platforms as well as the social-media industry's lack of

accountability and transparency about where ads appear. A

spokeswoman for Coca-Cola said the company is not officially

joining the Stop Hate For Profit boycott.

Facebook has said it plans to work with the Global Alliance for

Responsible Media, an initiative of the World Federation of

Advertisers, which is working on creating standards for what

constitutes hate speech and other advertiser-unfriendly content.

Facebook will also submit to its first-ever audit by the Media

Ratings Council. The aim is self-regulation, similar to the content

rating systems found in the videogame and film industries, says

Robert Rakowitz, head of GARM.

The businesses withholding ad dollars represent only a fraction

of Facebook's revenue, however. Most of that comes from small and

medium-size companies. But with public pressure still gaining

momentum, there's a chance more could come of this.

So what exactly might a "fixed" Facebook even look like? There

is little consensus.

Some focus on overhauling Section 230 of the Communications

Decency Act, which exempts internet platforms from liability for

the things people say and do on their platforms. Proposals to

curtail or end those protections for Facebook and its rivals have

come from both the right and the left.

Sen. Josh Hawley (R., Mo.) has suggested giving the Federal

Trade Commission expanded powers to review Facebook's

content-related decisions, examining them for bias.

Others, including Mr. Harris of the Center for Humane

Technology, think a better alternative could be something publicly

funded, a sort of Public Broadcasting System for social media. That

would be an enormously complicated new undertaking, with its own

tricky set of First Amendment issues.

Facebook has never been a company that stands mute in the face

of criticism. The company has in the past commissioned independent

human-rights assessments and promised sweeping changes. Just this

week, it announced it would delete hundreds of accounts and groups

devoted to the boogaloo movement, a loose confederation of mostly

young white men obsessed with guns, violence and perceived slights

to their freedom, which formed online and aims to start a civil war

in the U.S.

The endless game of Whac-A-Mole Facebook plays with these kinds

of fringe groups illustrates how much its strategy depends on

reaction to critics, says Mr. Harris. But it also reflects that,

with a service accessed by 2.6 billion people around the world, in

a hundred different languages, addressing all the possible ways

Facebook can be used -- and misused -- is virtually impossible, he

adds.

One of the Stop Hate For Profit movement's key requests is for

Facebook to appoint a C-level executive with deep civil-rights

expertise who examines products and policies for evidence of

discrimination and hate.

It is hard to imagine how that role would fit in Facebook's

hierarchy. Facebook has had senior executives with the power to do

such reviews, including Joel Kaplan, head of global public policy,

and Chris Cox, head of product, who just returned to Facebook a

year after departing over disagreements with Mr. Zuckerberg.

Mr. Kaplan, a conservative at a company whose employees

overwhelmingly lean liberal, has watered down or scuttled many of

the initiatives of engineers at Facebook that had the potential to

make its product less divisive with users, The Wall Street Journal

reported in May. He did this in part because he was concerned they

would disproportionately affect conservative media and voices on

the site, according to the Journal. Mr. Cox was responsible for

many of those failed initiatives before he left the company.

Facebook's response to the boycott campaign so far has mixed a

little fine-tuning with a lot of stay-the-course. Nick Clegg,

Facebook's vice president of communications, wrote on July 1 that

the company has a zero-tolerance policy toward hate speech, but

that finding hate on Facebook's 100 billion daily messages is like

finding a needle in a haystack. The company has tripled its safety

and security team to 35,000 people, he added.

The company also posted a list of responses to the specific

demands of the Stop Hate movement. Among these are expanding a

"brand safety hub" to let advertisers view their ads next to more

types of Facebook content. Expanding this would entail "substantial

technical challenges," the company said.

Another covered the question of potentially violating content in

private groups. The company said it's "exploring ways to make a

group's moderators more accountable for the content," but points

out that permitting or posting violating content already incurs

penalties that can result in a group being closed down.

In a June 26 post on Facebook, Mr. Zuckerberg announced that the

company will crack down on attempts at voter suppression leading up

to the November election, that Facebook identifies close to 90% of

hate speech posted to the site before anyone reports it, and that

the company will get tough on hate speech in advertisements. Mr.

Zuckerberg has also agreed to meet with organizers of the

boycott.

The organizers have zeroed in on the idea that above all, in

business, money talks. And their campaign could yet spur more

substantive action from Facebook. The boycott managed to depress

Facebook's stock price, but only temporarily. The extent of the

damage -- and the extent of Facebook's response -- will likely

depend on how big this boycott gets.

For more WSJ Technology analysis, reviews, advice and headlines,

sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Write to Christopher Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 02, 2020 17:21 ET (21:21 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

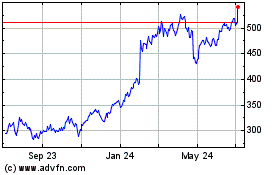

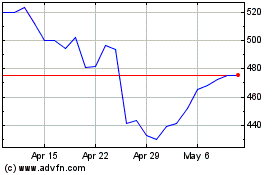

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024