By Emily Glazer

In a break with other tech companies, Facebook Inc. said it

wouldn't limit how political ads are targeted to potential voters,

but would instead give users tools to see fewer of those ads on its

platforms.

The move by Facebook, which says a private company shouldn't

decide how campaigns are able to reach potential voters, is at odds

with how other tech firms are approaching political ads leading up

to the 2020 election.

The social-media giant also announced changes it says will boost

transparency about how political ads are shared.

The company based its policy "on the principle that people

should be able to hear from those who wish to lead them, warts and

all, and that what they say should be scrutinized and debated in

public," according to a memo from Rob Leathern, Facebook's director

of product management. "This does not mean that politicians can say

whatever they like in advertisements on Facebook."

The memo said all Facebook users have to follow its community

standards, which ban hate speech, harmful content and content

designed to intimidate voters or stop them from exercising their

right to vote.

Facebook and other technology companies have faced increasing

pressure to limit the spread of misleading or false information.

Facebook took a different approach in its decision to increase

transparency and give users more control over what they see

compared with moves by Twitter Inc. and Alphabet Inc.'s Google to

largely block or limit targeting of political ads,

respectively.

Facebook acknowledged it considered limiting political-ad

targeting but ultimately chose not to do so. The company said it

consulted with a number of nonprofits, political groups and

campaigns--both Democrat and Republican--who, it said, consider

Facebook's platforms key ways to reach audiences.

"Ultimately, we don't think decisions about political ads should

be made by private companies, which is why we are arguing for

regulation that would apply across the industry," Mr. Leathern

said.

The announcement comes two days after the New York Times

reported on an internal post from Facebook executive Andrew

Bosworth, in which he said he believed the company played a central

role in the 2016 presidential election.

"So was Facebook responsible for Donald Trump getting elected? I

think the answer is yes, but not for the reasons anyone thinks. He

didn't get elected because of Russia or misinformation or Cambridge

Analytica. He got elected because he ran the single best digital ad

campaign I've ever seen from any advertiser. Period," Mr. Bosworth

wrote.

With less than a year until the 2020 U.S. election and roughly

$3 billion expected to be spent on digital political advertising, a

lack of uniform rules for the ads has led to confusion about

exactly what is allowed on the platforms, how intensely new

policies will be enforced and whether advertising strategies and

budgets will need to change further.

Political advertising will continue to increase with the first

Democratic presidential nominating contest in Iowa on Feb. 3.

Watchdogs including lawmakers and advocacy groups have called

for greater oversight of political advertising following

revelations that Russian entities purchased digital ads designed to

influence the 2016 presidential election.

Google earlier this week launched its new policy globally that

no longer allows advertisers to target political messages based on

users' interests inferred from their browsing or search histories,

among other changes. Twitter stopped accepting most political ads

in November. Facebook, meanwhile, in September said it would no

longer fact-check certain ads.

Facebook said its new control feature for political ads will

roll out in the U.S. early this summer on Facebook and Instagram.

It will later expand to other locations.

The company said seeing fewer political and social-issue ads was

a common request from users.

The expanded transparency features, which give users more

control over how advertisers reach them, will launch in the first

quarter of 2020. Those will apply to all countries where there is a

"paid for by" disclaimer on ads.

Facebook said while its users have been able to hide all ads

from a specific advertiser in their ad preferences, they will soon

be able to stop seeing ads based on how an advertiser constructed

its list of targeted users. In addition, users will be able to opt

in to see messages that are targeted to a group that doesn't

include them.

For example, Facebook said, if a campaign decided to stop

serving certain users fundraising ads because it deemed them

unlikely to donate, those users could choose to continue seeing

such ads.

The Wall Street Journal previously reported Facebook was

weighing steps to increase the minimum number of people who can be

targeted in political ads on its platform from 100 to a few

thousand, among other changes. The potential moves were being

considered as part of an effort to make it harder for advertisers

to microtarget, which has been criticized for enabling political

actors to single out groups for misleading or false ads that aren't

seen by the broader public.

Facebook said Thursday that its data showed more than 85% of ad

spending from U.S. presidential candidates is for ad campaigns

targeted to audiences estimated at more than 250,000 people.

"We recognize this is an issue that has provoked much public

debate--including much criticism of Facebook's position," Mr.

Leathern said. "We are not deaf to that and will continue to work

with regulators and policy makers in our ongoing efforts to help

protect elections."

Write to Emily Glazer at emily.glazer@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 09, 2020 06:14 ET (11:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

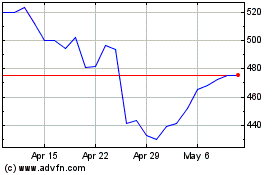

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

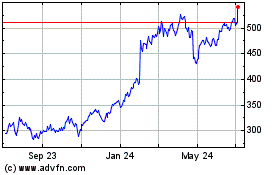

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024