By Mark Hulbert

It is perhaps fitting that the stock market plunged last month

as we approached the 20th anniversary of the top of the

internet-stock bubble.

On March 10, 2000, the Nasdaq Composite Index hit an intraday

high of 5132.52. We all know what happened next. By October 2002,

the index had fallen 78.4% -- to 1108.49.

And that was only half the agony. The other half was the index's

anemic recovery from that low. It took until November 2014 for the

index to battle back to its March 2000 level, even after taking

dividends into account. If you adjust for inflation, the index

didn't recover until August 2017, more than 17 years later.

If the Dow Jones Industrial Average were to follow the same

script, it would be trading at around 5400 in October 2022, and not

make it back to its current level until November 2034 (or, on an

inflation-adjusted basis, the summer of 2037). It is hard to

overestimate how devastating such a scenario would be for retirees

and soon-to-be-retirees.

How likely is this scary scenario? What investment lessons can

we draw with the perspective of 20 years' hindsight?

How unusual is it that the Nasdaq took so long to recover?

The Nasdaq's snaillike recovery after the dot-com crash doesn't

appear to have been unprecedented, at first blush. For example, it

wasn't until 1954 that the Dow Jones Industrial Average clawed its

way back to where it stood, on a point-for-point basis, before the

1929 crash -- a recovery time of 25 years.

In fact, however, stocks' real recovery from the 1929 crash took

a lot less than 25 years, for three reasons: The 30 stocks that

made up the Dow were below-average performers; dividends, which

were substantial in the 1920s and 1930s, helped restore losses; and

inflation, which was negative in the early 1930s, worked to stocks'

advantage. On a dividend- and inflation-adjusted basis, the broad

stock market had recovered from the 1929 collapse by March 1937,

only 7 1/2 years later.

Fast-forward to the early 21st century. It took the broad market

similar lengths of time to recover, on a dividend- and

inflation-adjusted basis, from the 2008-09 crisis (5 1/4 years) and

the bursting of the internet-stock bubble (7 1/2 years). The

longest recovery time in U.S. history was from the 1973-74 bear

market: It wasn't until the end of 1984 that the broad market, on

an inflation- and dividend-adjusted basis, was back to where it

stood at its January 1973 peak -- nearly 12 years later.

Note carefully, furthermore, that these recovery times were from

the worst bear markets of the past century. Taking into account all

U.S. bear markets since the mid-1920s, I calculate it took an

average of just 3.1 years for the broad market on a dividend- and

inflation-adjusted basis to make its way back to where it stood

before the bear market began.

So, the Nasdaq's plunge in 2000, and subsequent slow recovery,

is an outlier. No other bear-market recovery in U.S. history took

as long.

Diversification is still the key

To make a portfolio less vulnerable to the same kind of long,

drawn-out recovery as the Nasdaq market suffered, diversification

will be as important as it has always been.

Being narrowly concentrated in a relatively small number of

mostly younger companies, the Nasdaq market required more than

twice as long as the broader market to recover from the dot-com

crash.

And let there be no doubt that the Nasdaq market was poorly

diversified 20 years ago. Cisco Systems, the internet hardware and

software company, had the largest market cap of any stock in March

2000, and represented the largest share of any in the Nasdaq

Composite, which is a cap-weighted index. Over the two years

subsequent to the bursting of the internet bubble, the stock

dropped more than 90%.

The overall stock market today has become increasingly

concentrated, making it more difficult to achieve the level of

diversification that would otherwise ease bear-market losses. For

example, the five companies in the S&P 500 with the largest

market cap now make up more than 18% of the combined market cap of

all component companies. That is the most in U.S. history,

according to Morgan Stanley Research -- higher even than at the top

of the internet-stock bubble.

That means the S&P is becoming more vulnerable to the

idiosyncratic failures of a few large companies. Still, even though

the trend is worrisome, today's S&P is more diversified than

Nasdaq was: In contrast to the 18% of combined market cap that the

five largest companies in the S&P represent, the comparable

proportion for Nasdaq was more than 40%.

Valuations matter

The other investment lesson is that valuations matter, even

though they don't seem to when things are humming and some

investors are convinced that the rules have changed. At the top of

the internet bubble, for example, Nasdaq had a price/earnings ratio

of more than 100 when calculated on trailing 12 months' earnings --

and still 75 when based on estimates of subsequent 12-month

earnings. Both were many orders of magnitude higher than the broad

market's long-term P/E average of below 20.

To be sure, no valuation metric is perfect. But in hindsight,

the P/E ratio was a good indicator of the market's overvaluation,

and of weaker returns ahead: Since its March 2000 high, the Nasdaq

Composite, on an inflation- and dividend-adjusted basis, has

produced a return of just 1.3% annualized. The comparable return

for the S&P is 4.1% annualized, which is itself lower than the

6.8% average annualized return for the past two centuries.

Fortunately, the Nasdaq market's P/E ratio is a lot lower today

than 20 years ago: It stands at 26.4, when calculated based on

trailing 12-month earnings, and 22.2 when based on forward

estimates, according to Birinyi Associates. While these ratios are

significantly above average, they aren't nearly as inflated as they

were in March 2000.

Bottom line

The stock market is not as overvalued as it was 20 years ago,

and so long as you invest in a widely diversified index fund, your

recovery from the next bear market should be a lot faster than the

Nasdaq market's was from the bursting of the internet bubble. More

broadly, the past 20 years have taught us the importance of

diversification and paying attention to valuations. We should

resolve never to forget.

Mr. Hulbert is a columnist whose Hulbert Ratings tracks

investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be

reached at reports@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 08, 2020 23:27 ET (03:27 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

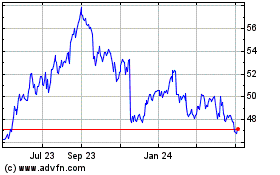

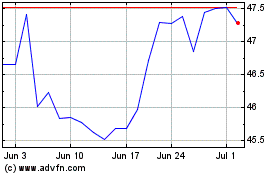

Cisco Systems (NASDAQ:CSCO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Cisco Systems (NASDAQ:CSCO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024