By Cezary Podkul

Georgia rolls out a red carpet for them at the Masters Golf

Tournament. Kentucky gets them tickets to the Kentucky Derby.

Arkansas takes them on a private duck hunt with the governor. Utah

recently arranged a private ski trip with an Olympic medalist.

Such is the life of site selectors -- consultants who jet around

the country helping corporations decide where to build new

headquarters, factories or expansion projects, often pitting

communities against each other in multistate bidding wars to

maximize tax breaks, grants, land deals and other incentives.

As communities across America race to win such marquee projects,

these middlemen have quietly become some of the most powerful

consultants in corporate America.

There are about 500 site selectors active in the U.S. and a 2017

survey found that 54% of companies plan to outsource part of their

next corporate location search, according to consulting firm

Development Counsellors International.

Amazon.com Inc. retained a site selection advisor, Alex Leath of

law firm Bradley, to work with its in-house team to sift through

238 proposals during its recent search for a second headquarters.

Site selectors from Ernst & Young LLP helped Foxconn Technology

Group secure the richest incentive package in Wisconsin state

history for its now-delayed liquid-crystal-display manufacturing

plant. Foxconn selected Wisconsin's package, which totaled more

than $4 billion in state and local support, after a multi-state

bidding war in which states jockeyed to sweeten their offers.

In some ways, the site selectors act like lobbyists, interacting

with government officials as they help their clients obtain

favorable deals that sometimes require legislative and regulatory

changes. Unlike lobbyists, site selection consultants often work on

commission, which is frequently tied to the size of the incentive

package they negotiate for their clients. That fee structure has

drawn criticism from some of the very economic development

officials who are competing against each other for the

projects.

Lee Crume, who heads an economic development group in Northern

Kentucky, thinks site selectors provide a valuable service to

companies, but they shouldn't be paid based on the size of the

incentives they negotiate.

Site selectors' ability to shape billions in public spending

decisions has also sparked criticism that the industry operates

with little oversight or disclosure requirements that apply to

corporate lobbyists.

"Winning legislative actions for discretionary incentives...I

think that's lobbying," said Greg LeRoy, executive director of Good

Jobs First, a nonpartisan policy group that is critical of

incentives. "They know that and legally don't want to be treated

like lobbyists."

Moreover, in the vast majority of cases, firms that receive

public incentives for opening factories, expanding headquarters or

creating jobs would have taken those actions even without a

sweetener, according to a pair of 2018 studies by the W.E. Upjohn

Institute for Employment Research.

Despite that, Upjohn research shows that the state and local

costs of incentives have at least tripled since 1990, reaching $45

billion annually as of 2015. Average incentive awards have also

tripled in size as a percentage of business taxes owed by the

companies receiving the perks.

What the incentives can alter, in some cases, is the location of

the project. That's fueling competition that has helped turn site

selection into a booming cottage industry.

"Kentucky Derby. Mississippi governor's quail hunt. Georgia

quail hunt...I've been to all of them," said Mike Mullis, a

Tennessee-based site selector. He works alongside his fiancée,

Denise Mott, at a site selection firm he founded in the 1970s, J.M.

Mullis Inc. The firm completes an average of about 50 projects a

year, according to its website.

Mr. Mullis has developed a reputation for being a tough

negotiator on incentives. When he represented Jeff Bezos's rocket

company, Blue Origin, on a site-selection search in 2016, a

Washington state official told the Puget Sound Business Journal

that Mr. Mullis "constantly hammered" the state to see what

incentives they could offer. Mr. Mullis told the paper that the

characterization was "pretty consistent with how we operated."

Blue Origin didn't respond to a request for comment.

Mr. Mullis was also an early member of an exclusive club of

consultants known as the Site Selectors Guild. New guild members

have to be approved by a committee, and every member is required to

attend a conference where government officials and other attendees

pay $2,000 a ticket for a chance to hobnob with them.

Guild members also get treated to extravagant parties and perks

by local communities that host the events. Like the hunting trips

and other events, they're often public-private partnerships.

Last year's festivities, held in Cincinnati, featured a private

reception at Paul Brown Stadium, where the Cincinnati Bengals play.

Site selectors were greeted on the field like NFL stars: plumes of

fire shot in the air and a squad of cheerleaders waved pompoms as

site selectors ran onto the field dressed in personalized Bengals

jerseys that awaited them when they arrived in the team's locker

room. One site selector, Jay Garner, got a chance to conduct the

string section of the Cincinnati Pops at a private event with the

orchestra. Mr. Garner, who describes himself as the conference's

"de facto entertainment guy," conducted Mozart's "Eine kleine

Nachtmusik."

Since its founding in 2010, the Guild has grown to include 50

consultants and now attracts 355 paid attendees at the marquee

event, which usually sells out within an hour, according to the

guild's executive director, Rick Weddle. Mr. Weddle says the

industry's mantra is that "incentives can never make a bad location

good. They can make a good location better." He said site selectors

help companies weigh a variety of factors, such as the availability

of qualified workers, access to infrastructure, proximity to

customers and suppliers, the cost of utilities and other production

inputs.

When the U.S. arm of Czech firearm maker Česká Zbrojovka began

looking for its first U.S. factory site last year, the company had

already committed to the expansion. Even if the subsidiary, called

CZ-USA, received no incentives, it still would have proceeded with

the project, said CZ-USA's chairman, Bogdan Heczko.

Still, he decided it would make sense to "see how much we can

get."

Mr. Heczko's company was originally deciding between two states

-- Kansas and Missouri -- which have a long history of competing on

incentives. Then CZ-USA hired Mr. Mullis to help with the search.

Mr. Mullis advised CZ-USA to broaden the search to more states,

according to Mr. Heczko. Mr. Mullis said he helped the firm scout

locations in a dozen states, including Arkansas.

In early December, Mr. Mullis and a handful of other site

selectors spent the day hunting at a private retreat with Arkansas

Gov. Asa Hutchinson. Mr. Mullis said events like these are good

"relationship-building" opportunities.

At the end of the day, as Mr. Mullis relaxed on a couch in a

spacious hunting lodge in Northeast Arkansas, Mr. Hutchinson

approached him to ask for his advice on how to attract the gun

manufacturer to his state.

"What do we need to do to close this deal? We want this

project," Mr. Hutchinson said, according to Mr. Mullis.

Mr. Hutchinson confirmed in an interview that Mr. Mullis gave

him advice on how to "fine-tune" Arkansas' pitch to his client. He

also said Mr. Mullis "is a very good shot."

Mr. Hutchinson -- who has okayed 435 incentive deals since

becoming governor in 2015 -- ultimately allocated $4 million from a

fund he controls, the "Quick Action Closing Fund," to pay for

improvements at the site in Little Rock selected by CZ-USA. That

was in addition to more than $20 million of loans, rebates, tax

breaks and other incentives Mr. Mullis helped negotiate. The

company pledged to invest $90 million and create 565 jobs,

according to a press release.

Site selectors sometimes explicitly ask for legislative changes

to accommodate their clients. And when the deal is big enough,

officials move quickly to act on those demands.

In the spring of 2017, Ernst & Young sent Wisconsin and

other states a request for proposals for an investment opportunity

it identified only as "Project Flying Eagle." The document included

an explicit request that governments "provide offsets to all taxes

levied at the state and local level" and "propose potential

administrative and/or legislative changes" if they are "unable to

close the cost differential" with the company's existing

manufacturing facilities in Asia.

At least three states -- Wisconsin, Ohio and Michigan -- made it

to the final round of bidding for what turned out to be the Foxconn

plant, according to interviews and documents disclosed under public

records requests.

After back-to-back pitches from the states' governors, Ernst

& Young worked with state officials to help the company

maximize incentives, according to a person involved in the

confidential negotiations.

"All they did was ask for more money," the person said.

Michigan raised its offer twice, according to documents the

state provided under a public records request. The state's package

of discretionary incentives rose from about $1.7 billion in May

2017 to $4.4 billion to about $4.5 billion by late June. Including

other available exemptions already on the books, Michigan package

totalled around $7 billion, although many of the promised tax

breaks would have paid out later than Wisconsin's package.

Correspondence between Wisconsin and Ernst & Young shows

that state also sweetened its offer during the process. A spokesman

for the state's economic development arm said the boost was

justified because the scope of the project had increased.

The administration of Wisconsin's then-Gov. Scott Walker relied

on an economic-impact study provided by E&Y to craft a package

of tax credits, infrastructure improvements and other incentives

for Foxconn, emails show. The state's share was about $3 billion

and wouldn't result in a positive return to taxpayers until 2042,

according to a state review of the incentives published by

Wisconsin's Legislative Fiscal Bureau. But if everything would pan

out as expected, Wisconsin would gain 13,000 jobs and be home to a

$10 billion liquid crystal display manufacturing plant, the first

in the U.S.

Ernst & Young's study was cited by Wisconsin officials as

they sold Foxconn's incentive package to the state legislature.

Gov. Walker called a special legislative session to pass the bill,

which became law in seven weeks.

Ernst & Young executives said in a 2018 article on

maximizing incentives that such studies can be useful as a "public

relations tool" to "build support" for a project.

Timothy Bartik, a senior economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute

for Employment Research, reviewed Ernst & Young's economic

impact study of Foxconn's investment in Wisconsin. Mr. Bartik said

the study wrongly assumed that the added jobs wouldn't result in

any additional costs to governments, such as increased costs to

schools or added spending on roads. Additional costs like these can

overshadow the value of any incremental tax revenues generated by

the employment.

"I think a true fiscal analysis would show that this project

will NEVER break even fiscally, until the Sun turns into a red

giant," Mr. Bartik said in an email.

Since Wisconsin inked the deal, Foxconn has scaled back its

ambitions in Wisconsin. The company said in a January letter to the

Wisconsin Economic Development Corp. that it has "adjusted our

recruitment and hiring timeline" and had created fewer than 200 of

13,000 jobs it had promised.

Foxconn also said it would forgo the $9.5 million of job

creation credits the company was eligible for in 2018 under its

contract with Wisconsin. The company declined to comment.

Wisconsin Economic Development Corp. Chief Executive Mark Hogan

said in an interview that Foxconn's incentives are

performance-based and meant to provide the company flexibility to

adapt to changing circumstances. "We came up with what we felt was

the best deal for the state of Wisconsin and the taxpayers," he

said.

In a meeting with the Journal, Ernst & Young's site

selection leader, Paul Naumoff, declined to comment on his

company's work for Foxconn, citing client confidentiality. A

spokeswoman who attended the meeting advised him not to answer when

a reporter asked if site selection work bears similarities to

lobbying.

Incentives aren't always the key factor in companies' relocation

decisions.

When Amazon searched for a home for its second headquarters, the

availability of a skilled workforce was the top concern. "This was

really about talent," Holly Sullivan, Amazon's head of world-wide

economic development, said at the Site Selectors Guild's annual

conference in March.

The event was held at the Grand America, a luxury hotel in Salt

Lake City featuring a landscaped garden and harp concerts in the

lobby. Perks included a cowboy attire-themed dinner with Utah Gov.

Gary Herbert at the Grand Hall of the Union Pacific Depot and a

site selectors-only ski trip with a two-time Olympic medalist,

Shannon Bahrke. There was also a dance party featuring a Motown

band. Mr. Garner, the site selector who conducted Mozart in

Cincinnati, sat in to play drums to Duke Ellington's "Don't Get

Around Much Anymore."

It was hard to find any part of the event that didn't have a

state logo on it. Louisiana paid for the Wi-Fi; South Carolina paid

for breakfast. Each cost $10,000. A chance to spend an hour at a

private cocktail party with the guild's members also cost a good

amount. "I paid $20,000 to go to this thing," said one state

official as he waited to go in to the "silver sponsors"

reception.

Like the competitive bidding process used by site selectors, the

selection of the conference location itself was conducted via a

request for proposals. A winning bid can cost upward of $100,000,

according to two economic development officials who hosted past

conferences.

Val Hale, executive director of the Utah Governor's Office of

Economic Development, said it is money well spent. "This is the

Super Bowl of economic development events," he said.

The conference was the brainchild of Robert Ady, an industry

veteran who founded the Guild in 2010 after realizing that economic

development officials would pay for the privilege of spending time

in the presence of site selectors. (Mr. Ady died in 2012, the first

year the annual conference was held.) The Guild runs as a

for-profit corporation owned by members and the annual event is its

main moneymaker.

True to its founder, incentives remain an agenda item at the

conference. According to Mr. Ady's daughter, Janet Ady, he used to

say that "you'll never know if you paid too much in incentives.

You'll only know if you didn't pay enough."

Write to Cezary Podkul at cezary.podkul@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 18, 2019 00:14 ET (04:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

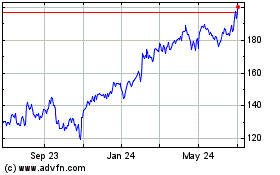

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024