By Katie Deighton

Dagmar Munn and her husband purchased a smart speaker from

Amazon.com Inc. for their home in Green Valley, Ariz. in 2017,

seven years after Ms. Munn was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis, the motor neuron disease more commonly referred to as

ALS.

At first the speaker's voice assistant, Alexa, could understand

what Ms. Munn was saying. But as her condition worsened and her

speech grew slower and more slurred, she found herself unable to

communicate with the voice technology.

"I'm not fast enough for it," Ms. Munn said. "If I want to say

something like 'Alexa, tell me the news,' it will shut down before

I finish asking."

Ms. Munn can't interact with voice assistants such as Alexa

because the technology hasn't been trained to understand people

with dysarthria, a speech disorder caused by weakening speech

muscles. People with a stutter or nonstandard speech caused by

hearing loss or mouth cancer can also struggle to be understood by

voice assistants.

Approximately 7.5 million people in the U.S. have trouble using

their voices, according to the National Institute on Deafness and

Other Communication Disorders. Julie Cattiau, a product manager in

Google's artificial intelligence team, said that group is at risk

of being left behind by voice-recognition technology.

Google is one of a number of technology companies now trying to

train voice assistants to understand everyone.

Some made investments into voice accessibility after realizing

that people with dysarthria -- often a side effect of conditions

including cerebral palsy, Parkinson's disease or a brain tumor --

may be the group that stands to benefit most from voice-recognition

technology.

"For someone who has cerebral palsy and is in a wheelchair,

being able to control their environment with their voice could be

super useful to them," said Ms. Cattiau. Google is collecting

atypical speech data as part of an initiative to train its

voice-recognition tools.

Training voice assistants to respond to people with speech

disabilities could improve the experience of voice-recognition

tools for a growing group of potential users: Seniors, who are more

prone to degenerative diseases, said Anne Toth, Amazon's director

of Alexa Trust, a division that oversees the voice assistant's

privacy and security policies and features, as well as its

accessibility efforts.

Amazon in December announced an Alexa integration with Voiceitt,

an Israeli startup backed by Amazon's Alexa Fund that lets people

with speech impairments train an algorithm to recognize their own

unique vocal patterns. Slated to go live in the coming months, the

integration will allow people with atypical speech to operate Alexa

devices by speaking into the Voiceitt application.

Apple Inc. said its Hold to Talk feature, introduced on

hand-held devices in 2015, already lets users control how long they

want the voice assistant Siri to listen for, preventing the

assistant from interrupting users that have a stutter before they

have finished speaking.

The company is now researching how to automatically detect if

someone speaks with a stutter, and has built a bank of 28,000 audio

clips from podcasts featuring stuttering to help do so, according

to a research paper due to be published by Apple employees this

week that was seen by The Wall Street Journal.

The data aims to help improve voice-recognition systems for

people with atypical speech patterns, an Apple spokesman said. He

declined to comment on how Apple may use findings from the data in

detail.

Google's Project Euphonia initiative is testing a prototype app

that lets people with atypical speech communicate with Google

Assistant and smart Google Home products by training software to

understand their unique speech patterns. But it's also compiling an

audio bank of atypical speech that volunteers -- including Ms. Munn

-- contribute to.

Google hopes that these snippets will help train its artificial

intelligence in the full spectrum of speech and bring its voice

assistant closer to full accessibility, but it isn't an easy task.

Voice assistants can recognize most standard speech because users'

vocal harmonies and patterns are similar, despite their different

accents. Atypical speech patterns are much more varied, which makes

them much harder for an artificial intelligence to understand, said

Google's Ms. Cattiau.

"As of today, we don't even know if it's possible," she

said.

Critics say technology companies have been too slow in

addressing the issue of accessibility in voice assistants, which

first became available around 10 years ago.

Glenda Watson Hyatt, an accessibility advocate and motivational

speaker who has cerebral palsy, said some disability surveys don't

report on the prevalence of speech disabilities, so if technology

companies "relied on such data to help determine market size and

needs, it is obvious why they overlooked or excluded us."

People working in voice accessibility say the technology only

relatively recently became sophisticated enough to attempt handling

the complexities of nonstandard speech. They also said many

technology firms weren't placing so much emphasis on inclusive

design when the first voice assistants were being built.

Contributing to projects such as Project Euphonia can also be

difficult for people with atypical speech. Ms. Munn says she

sometimes finds speaking physically exhausting, but is happy to

contribute if it helps teach a voice assistant to understand

her.

"It would help me feel normal," she said.

Write to Katie Deighton at katie.deighton@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 24, 2021 12:15 ET (17:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

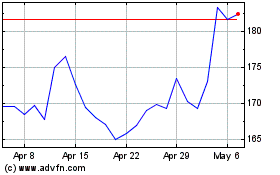

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

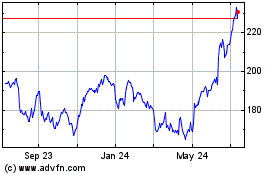

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024