By Nick Kostov and Sean McLain

BEIRUT -- As dusk settled over the capital of Lebanon, Carlos

Ghosn took a seat in the back corner of a dimly lit restaurant a

short walk from his house. A waiter approached. In Arabic, Mr.

Ghosn ordered an espresso.

A bodyguard, after looking the place over, disappeared. Several

groups of Lebanese businessman talked quietly nearby, paying little

mind to the former auto titan who had made world-wide headlines

weeks earlier by escaping house arrest in Tokyo and fleeing Japan

after sneaking onto a private plane in a large black box.

Mr. Ghosn's new life in Lebanon, he said between sips of

espresso, is one of restrictions. He can't leave the country where

he was born without risking arrest, and Lebanon's banking crisis

has crimped his access to cash. At times, street protests have made

even moving around the city a challenge.

And always, he is on the lookout for Nissan or Japanese

authorities who might be shadowing him.

"I've been told I need to protect myself," he said. "Even the

building in front of my house, Japanese people came to rent it. I

don't know what their intentions are. People tell me that a lot of

Japanese people are coming, taking photos and observing."

His life of hopscotching around the world on a private jet, he

knows, is over. His primary focus these days is mounting his

counterattack against charges that as head of the auto-making

alliance between Renault SA and Nissan Motor Co., he

misappropriated company money and hid compensation. "We're talking

about fighting for my reputation, fighting for my legacy and

fighting for my rights," he said. "I've never been as motivated as

I am today."

Asked whether he has anything to apologize for in the wake of

his escape, his eyes narrowed. "Apology for what...?" he said. "For

who? Nissan? Renault?"

Mr. Ghosn's return to the homeland he left as a teenager is a

strange twist of fate for an executive that has long considered

himself a citizen of the world, accumulating homes and passports on

multiple continents. All four of his children grew up between Paris

and Tokyo before studying at Stanford University. None of them

speak Arabic.

"Since I started to work, this is the longest period I spent in

Lebanon, " Mr. Ghosn said.

Today, the country that once put his face on a postage stamp is

buffeted by violent protests demanding the overthrow of the

Lebanese establishment. "Carlos Ghosn is one of them," said Ahmad

Jammoul, a 21-year-old student who marched in a recent protest.

A spokeswoman for Mr. Ghosn responded that he "is not part of

the Lebanese establishment, has no political role in the country

and does not plan to have any."

The timing of his return hasn't helped. Mr. Ghosn mounted a

costly escape operation -- chartering a private jet to smuggle

himself out of Japan in an audio-equipment box, and forfeiting

close to $15 million in bail money -- while Lebanon was in the

middle of a financial crisis.

Lebanon's borrowing costs soared as investors fled its

sovereign-debt market. Banks, the main holders of Lebanese bonds,

have responded to a cash crunch by restricting customers' access to

their money, including the amounts that can be transferred abroad.

Mr. Ghosn is consulting Hollywood agent Michael Ovitz about selling

his story for film and TV, and has told friends it could help

finance his legal battle.

The latest protests started in October, after the government

proposed a tax on WhatsApp, the popular messaging app. They turned

violent as anger grew at the country's political class, whom people

blame for the collapsing economy.

"This thinking that there is no solution for the problems in

Lebanon, I don't buy it," Mr. Ghosn said. "There is a solution. But

the solution on paper is maybe 5%, but then it's 95% execution.

Same as companies."

Walid Jumblatt, a lawmaker at the center of Lebanese politics,

has called for Mr. Ghosn to be named the country's energy minister.

Mr. Ghosn said he has no interest and that he steers clear of

Lebanon's sectarian politics.

For the first time in decades, Mr. Ghosn has time on his hands.

He and his wife have been hosting dinners for friends inside their

Beirut mansion. He has been reconnecting with childhood classmates,

visiting old haunts, skiing and walking in the mountains. On

Tuesday, he and his wife heard the Lebanese Philharmonic Orchestra

play Beethoven's Symphony No. 5.

"I need to recover," he said. "Physically, the 14 months in

Japan have been a challenge."

One afternoon last month, he took his 25-year-old son, Anthony,

for the first time to visit the apartment where he grew up. It is

in a working-class neighborhood encircling the ruins of a

fifth-century church. A stronghold of the Maronite Christian

community, the neighborhood has changed little since he left.

A 64-year-old cafe owner tried to approach Mr. Ghosn but was

stopped by his bodyguard. He identified himself as a distant

cousin. The bodyguards backed off.

"Welcome to Lebanon," the man said, explaining to Mr. Ghosn that

they were connected by marriage through a distant relative.

Where was that relative now? Mr. Ghosn asked. The man pointed to

an apartment building across the street from Mr. Ghosn's childhood

home.

Mr. Ghosn was born in Porto Velho, Brazil, in the Amazon jungle,

to Lebanese parents.

His father, Georges Ghosn took the family back to Lebanon when

Mr. Ghosn was 6 years old. Around that time, Georges Ghosn was

arrested for his involvement in the murder of a priest who was shot

twice, once in the head.

Police said Georges and the priest had been smuggling diamonds

and foreign currency, Lebanon's main French language daily

newspaper reported at the time. Mr. Ghosn's father admitted to the

trafficking but maintained he didn't pull the trigger in the

shooting, the paper said. His sentence was commuted to 15 years of

hard labor after a court ruled the killing wasn't premeditated.

Georges got an early release from jail, when Mr. Ghosn was 16

years old. Four months later he was caught with about $35,000 in

counterfeit cash, the Lebanon paper reported. He was sentenced to

another three years in prison.

Mr. Ghosn declined to comment on his father. His father's

imprisonment was a painful episode for him, said one person who has

spoken to him about it. "It's a credit to him that he overcame it,"

this person said.

In a 2003 autobiography, Mr. Ghosn described his father as a

devout Maronite who shuttled between Brazil and Lebanon for work.

The book didn't mention his imprisonment.

Mr. Ghosn wrote that Lebanon in those days was "the Switzerland

of the Middle East," a sun-kissed financial center that drew

tourists from around the world.

His mother sent him to a private Jesuit school, Notre Dame de

Jamhour, where he was a stellar pupil with a rebellious streak.

Elie Gharios, a childhood friend, said he and young Carlos once

were suspended for writing "down with old people" in red paint on

the side of the 170-year-old school. The future auto executive was

often surrounded by other boys who followed his every order, Mr.

Gharios recalled.

In 1971, Mr. Ghosn graduated from high school and moved to Paris

to continue his education. It was in France that peers started

using a Western pronunciation of his name, with a hard "g" and a

silent "s" in a way that rhymes with "cone." In Arabic, the name

sounds more like "Ho-ssun."

As Mr. Ghosn's auto-industry career took off, he seldom visited

Lebanon. His first major assignment as a young manager at the tire

maker Michelin was in Brazil. People who know him from that period

say he didn't look back.

In 2008, he bought a large stake in a vineyard in Lebanon. A few

years later, after a 2012 divorce, he married his second wife,

Carole. She came from the same Maronite neighborhood in Beirut.

In 2012, Nissan purchased for Mr. Ghosn's use a villa in the

city's Ashrafieh quarter, a neighborhood of stately mansions and

apartments buildings that had given the city its former moniker,

the Paris of the Middle East. Nissan paid about $9.4 million, then

sunk another $7.6 million into renovating it. Carole Ghosn

supervised the job, which included painting the exterior pink and

excavating two ancient sarcophagi now visible beneath a glass floor

leading to the wine cellar.

Mr. Ghosn's arrest in Nov. 2018 marked the start of a yearlong

tug of war with the Japanese justice system. After spending months

in prison, often in solitary confinement, he was assigned to live

in a Tokyo apartment with camera surveillance and a court order

barring contact with his wife, then shuttling between Lebanon and

New York City.

Jumping bail and fleeing to Lebanon reunited Mr. Ghosn with his

wife and gave him a measure of freedom. Interpol issued a "red

notice," indicating he was wanted by Japan for extradition. But

Lebanon doesn't extradite its citizens, which means that Mr. Ghosn

is unlikely to return to face trial in Japan.

Tokyo's deputy chief prosecutor, Takahiro Saito, said in a

written statement that Mr. Ghosn "didn't want to submit to the

judgment of our nation's courts and sought to avoid the punishment

for his own crimes."

Nissan had changed the locks at the Beirut villa after his

arrest, but a Lebanese court ordered the company to hand the new

keys over to Carole Ghosn while the court reviews the matter.

Nissan is trying to evict the Ghosns, and the Ghosns are trying to

buy the house from the company.

After he stepped off a chartered jet in Beirut on Dec. 30, Mr.

Ghosn began laying the groundwork for his new life. He immediately

visited Lebanon's president, who hadn't been warned of Mr. Ghosn's

escape plans, according to people familiar with the matter. His

Lebanese lawyer, who has extensive political contacts in Beirut,

dialed politicians and newspaper editors to gauge their support for

Mr. Ghosn's decision to take refuge in Lebanon.

Mr. Ghosn has been mounting his legal and public-relations

campaign against Nissan and the Japanese government with the zeal

he once brought to running Nissan-Renault. Several times a week, he

takes a car to his Lebanese lawyer's office in central Beirut.

The firm has provided him with a small, corner office

overlooking a school and a church. He uses a videoconferencing room

next door to talk to his other lawyers and public-relations

advisers in Tokyo, Paris and New York.

"I have to take care of myself," he said. "I don't have to take

care of all these companies. I work with a more restricted group of

people. They've been through a lot of battles, but people I can

really count on."

He has filed a lawsuit against Renault alleging the French car

maker owes him a EUR250,000 pension payment after he stepped down

as chairman and chief executive while inside a Tokyo jail. His

lawyers have filed a lawsuit in an Amsterdam court alleging that

Nissan and Mitsubishi unfairly dismissed him as a director at the

companies' Dutch joint-venture. Lawyers representing the joint

venture have said Mr. Ghosn's dismissal was justified.

"It's an unbalanced fight," he said. "The companies have deep

pockets."

Lebanese officials have asked Mr. Ghosn to not say anything that

might create tension between Beirut and Tokyo. That meant toning

down his first public appearance since his escape -- a Jan. 8 news

conference in which he berated Nissan and the Japanese justice

system.

Mr. Ghosn had considered criticizing the Japanese government and

accusing officials of conspiring with Nissan in his downfall,

according to people familiar with the matter. Nissan and J apanese

prosecutors have denied that they conspired to bring down Mr.

Ghosn. Prosecutors said they conducted their own investigation.

On the eve of the news conference, Lebanese officials asked him

to refrain from attacking Japanese officials, these people said. A

spokesperson for the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that

before the news conference, Japan's ambassador to Lebanon had told

Lebanon's president that Mr. Ghosn's "illegal departure from Japan

and arrival in Lebanon is deeply regrettable and can never be

overlooked by the government of Japan."

Lebanese government officials didn't respond to requests for

comment.

In Lebanon, it is a crime for a private citizen to harm

Lebanon's relations with another country.

"I would do nothing beyond reasonable to jeopardize the

relationship between the countries," Mr. Ghosn later said.

Mr. Ghosn also used the news conference to try to quell a

separate controversy. A group of lawyers had petitioned a Lebanese

court to arrest Mr. Ghosn for a trip he made to Israel in 2008 when

he was CEO of Renault. Lebanese citizens are barred from visiting

that country because the two states are still technically at

war.

Mr. Ghosn's legal team countered the petition in court by saying

he made the visit as the head of a French company and shouldn't

face prosecution.

Addressing the TV cameras in Arabic, Mr. Ghosn sounded a note of

contrition. "Of course I apologize for the visit, and I was very

moved that the Lebanese people were affected by it," he said. "The

last thing I wanted to do was hurt the Lebanese people."

--Nazih Osseiran contributed to this article.

Write to Nick Kostov at Nick.Kostov@wsj.com and Sean McLain at

sean.mclain@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 22, 2020 00:16 ET (05:16 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

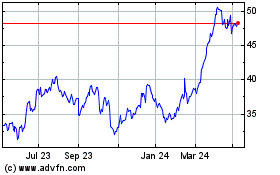

Renault (EU:RNO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

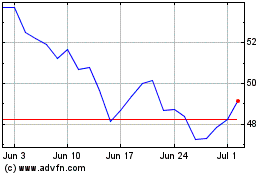

Renault (EU:RNO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024