Hit Game Spurs Trespassing Suit -- WSJ

April 05 2017 - 3:02AM

Dow Jones News

By Sara Randazzo

Annoyed homeowners say "Pokémon Go" players have gone too far in

their quest to master the smartphone game -- and they want the

company behind the hit application to be held responsible.

A federal judge is poised to decide if a lawsuit alleging the

game's developer violated trespass and negligence laws can go

forward, a ruling that could have broader implications for makers

of games or other software that send users to specific

locations.

"Pokémon Go," based on the Japanese franchise popularized by

Nintendo Co. in the 1990s, sends millions of players each day

searching for Pokémon characters on a digital map. Players gain

points by catching the monsters, which appear superimposed into the

real world through location-tracking technology and augmented

reality.

The court decision is expected in the coming weeks in a case

brought by residents in New Jersey, Florida and Michigan. They say

the popular game caused hordes of people to physically trespass on

their land. They also say the game violates their rights by placing

virtual game pieces on or near their private property without their

permission.

The lawsuit raises novel legal questions over whether a company

can be held liable for the allegedly inappropriate conduct of

others, or be found responsible for virtual trespassing. Both

issues are likely to gain relevance as more augmented-reality games

hit the market. Such games use the Global Positioning System,

camera and other elements of a player's smartphone to tether play

to their physical surroundings.

"The law here is very messy," said Shawn Bayern, a law professor

at Florida State University. "Each state handles it slightly

differently."

In a series of lawsuits filed after the launch of "Pokémon Go"

in July, plaintiffs claim smartphone-toting players caused

disturbances as they hunted for virtual game characters placed at

specific GPS coordinates.

Residents of the Villas of Positano on the South Florida coast

said hundreds of people began infiltrating the 62-unit complex,

parking illegally and even relieving themselves in the landscaping

during late-night visits to "catch" virtual characters. Another

plaintiff, a New Jersey lawyer, said at least five people knocked

on his door asking for access to his backyard.

In Michigan, a couple said a quiet nearby park became overrun

once it was tagged as a location in the game, creating a nightmare

for neighbors as players stormed the area, blocked driveways and

peered in windows. The separate lawsuits were consolidated in U.S.

District Court in San Francisco and seek class-action status.

The intrusions, the plaintiffs say, amount to negligence and

trespassing by the game's developer, Niantic Inc. They claim not

only that Niantic is responsible for players who physically

trespassed, but also that the placement of the virtual characters

is itself a form of trespassing.

Legal experts say trespass and negligence laws vary in each

state and that little, if any, case law exists over how to handle

virtual intrusions.

Key to both laws is the intent of those allegedly trespassing or

causing a nuisance and whether actual harm occurred. Finding a way

to adapt the laws to situations like those raised in the lawsuit is

"something that needs to be addressed over the long run because the

technology is not going away," said Gregory Keating, a professor at

the University of Southern California Gould School of Law.

Niantic, which spun out of Alphabet Inc.'s Google in 2015, is

asking a judge to dismiss the case and says the plaintiffs are

distorting the law. The company argues that trespass laws only

cover physical intrusions, not virtual ones. Such a virtual

intrusion "is less invasive than noise, vibrations, dust, or a

chemical cloud, all insufficient for trespass," Niantic says in a

court filing.

Niantic argues that if software developers are prevented from

tying on-screen virtual objects to locations or sending users to

specific places, many online services would be threatened. Those

could include websites or mobile applications listing real estate

open houses or locations where rare birds have been spotted, or

navigation systems pointing out shortcuts, "all of which can

attract visitors and impact nearby residents," Niantic said.

They further argue that the game requires users to agree not to

trespass as a condition of playing, and that if a player

overstepped his or her bounds, it shouldn't fall on them. "Niantic

does not control millions of players' real-world movements," the

company said.

That argument may not hold up in court, said John Nockleby, a

professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles. The company can't

hide behind a boilerplate user agreement, he said, if they know a

million users will be tempted to trespass if they place a virtual

Pokémon on private property.

The initial fever around "Pokémon Go" has subsided, though

several million U.S. users still play it daily and it generates

more than $30 million in monthly gross revenue world-wide,

according to market-research firm Sensor Tower Inc.

--Sarah E. Needleman contributed to this article.

Write to Sara Randazzo at sara.randazzo@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 05, 2017 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

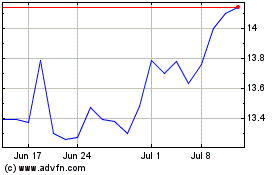

Nintendo (PK) (USOTC:NTDOY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Nintendo (PK) (USOTC:NTDOY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024